COVID kicks like a mule, which is why I failed at my goal, and why I’m just getting this information out about my next session of classes.

|

| Oops. |

I set out two weeks ago on an impromptu excursion with my son to West Yellowstone, Montana. We would look at geysers in the snow, and celebrate his Prius clicking over 300,000 miles, which we calculated would happen somewhere on the NYS Thruway as we returned to Albany, NY.

I was last in Yellowstone 26 years ago with a baby in a backpack saying “bub-ble”. On this trip, her younger brother was more erudite. He’s a newly-minted geologist. I now know more about the Yellowstone Supervolcano than I ever thought possible.

|

| Coyote at Yellowstone, photo courtesy Dwight Perot. |

On Monday of last week, my husband told me he had COVID. I was starting to develop cold symptoms myself, but according to the CDC we’d been apart too long for me to have been exposed with him. However, by Tuesday morning, it was apparent that my son and I also had COVID. We decided to beat feet back home.

If you’re not feeling well, a car provides a strange insulation. You stop at roadside rest stops, you eat fast food, you sleep, and then you do it all over again. It’s amazing how fast you can travel 2600 miles when you’re self-quarantined.

|

| Yellowstone in the snow, photo courtesy Dwight Perot. |

One problem became evident as we approached Ohio. We would be 55 miles short of our 300,000-mile goal. “No problem,” I said. “We’ll just take a fast run up the Northway when we get back to Albany.”

Except that we couldn’t. Even in its Omicron form, COVID has a wicked kick. I left the boy on his sickbed, drove home and slept all weekend.

|

| Yellowstone River, photo courtesy Dwight Perot. |

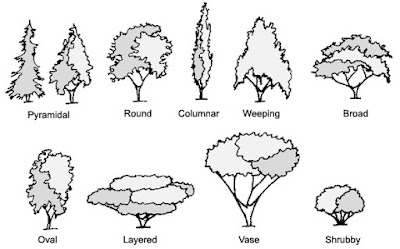

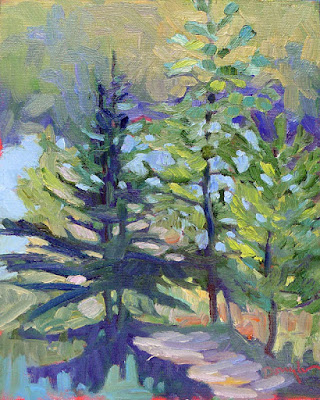

That’s why I’m just getting around to telling you about my openings for my next session of Zoom classes. There are three seats open in each class. (My current students always have first dibs on returning.)

These classes are open to intermediate painters in watercolor, acrylics, pastels and oils. What do I mean by that? You have a basic understanding of how to apply paint, but want to learn more about how to paint boldly, use fresh, clean color, build commanding compositions, and draw the eye through your paintings. (If you need a beginner class, contact me and I’ll put you in contact with some excellent teachers.)

The great thing about Zoom classes is that they’re one place you can’t spread a virus. And having just done COVID myself, I think that’s an awesome thing.

ZOOM Tuesday morning Session

We meet on Tuesdays from 10 AM to 1 PM EST, on the following dates:

February 22

March 1, 8, 15, 29 (off week of March 21 for Sedona workshop)

April 5

ZOOM Monday evening Session

We meet on Mondays from 6 to 9 PM EST, on the following dates:

February 21, 28

March 7, 14, 28 (off week of March 21 for Sedona workshop)

April 4

For more information, see here.