Time for art class. Get out your pencils and get started.

|

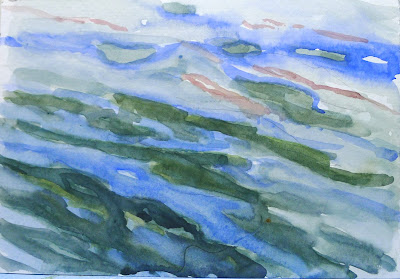

| Reflections off American Eagle in Stonington, watercolor, by Carol L. Douglas |

Artists often trip up on the

stochastic processes: things that have a general pattern but can’t be predicted precisely. We tend to either ignore the pattern altogether or overstate it into rigid regularity. These are everywhere in nature: in the distribution of leaves on trees, wildflowers in fields, the cleaving of rocks, and the behavior of water.

The surface of water is one of the most fascinating and difficult things to paint. It can be utterly still, or random and choppy, or it can create orderly patterns of surface ripples or waves. When it hits an obstacle like a ledge or the shore, its surface behavior is dictated by what’s underneath. In a rainstorm, fresh water floats on the surface of salt water, adding another pattern.

I like to sketch what the surface of water is doing. This changes quickly, so it helps to do this in a fast-working medium like pencil or watercolor. I did the above sketch while anchored off Stonington last week, but you don’t need an ocean for this exercise. There’s standing water almost everywhere: in ponds, lakes, or streams.

|

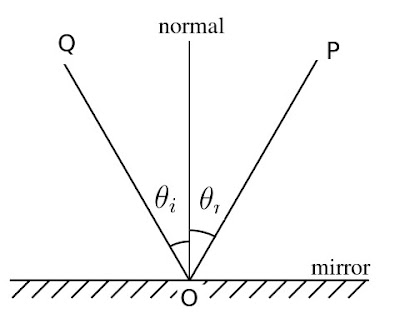

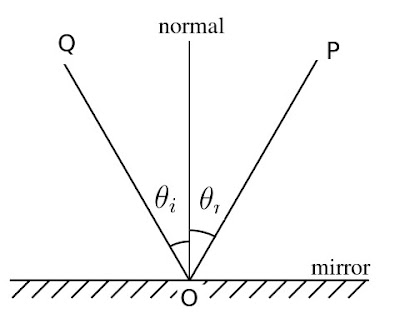

| Light reflects identically but opposite. That’s immutable. What changes with water is the shape of the surface. |

Reflection involves two rays – an incoming (incident) ray and an outgoing (reflected) ray. Physics tells us that the angles are identical but on opposite sides of a tangent. This is immutable. It’s why reflections that do not run in a generally-straight line down to the viewer are always wrong.

If water were perfectly still and perfectly reflective, its surface would be a mirror. Two factors prevent that. First, some rays of light are absorbed, and not reflected. This is true in both directions. Some of the light from the sky is absorbed. At the same time, we can see some of the color (or objects) under the water. Furthermore, the surface is never flat; it’s wavy or worse, just like a fun-house mirror.

|

| The surface of the water at the Isaac H. Evans’ berth in Rockland. |

In most cases, a sea wave’s surface is also windblown and irregular. That makes its surface infinitely varied. Rays are reflected at many different angles, radically disrupting the image. This gives the surface of the sea or its spray a solid or matte appearance.

Where we see directly into water, it’s the least reflective. That can either mean looking straight down or into the face of the wave. These surfaces are most likely green or brown in tone, depending on what’s underneath. The tops of the waves reflect the sky, but the sky isn’t the same color in all directions. Other surfaces reflect what’s in the distance—moonlight, other boats, structures, trees. Often these last reflections take the form of rings.

|

| In relatively still water, reflections are irregularly elliptical. |

In relatively still water, reflections are generally elliptical, although those ellipses may join in long strings or have vibration interference depending on the surface breeze. As the water becomes less still, water generally sorts itself into waves with identifiable patterns.

Waves can range from very tiny ripples to towering structures nearly a hundred feet tall. Most of us see waves as they approach the shore. There their behavior changes radically. They tend to pile up as the water gets shallower, effectively growing taller and slowing down. As they break, all predictability ends. The spray from a breaking wave can and does go anywhere.

|

| The light stream is fresh water on top of salt water during a rainstorm. |

Your assignment, then, is to find a body of standing water somewhere near you, and draw or paint the reflections. Don’t worry about the setting; we are only concerned with the behavior of the waves you are seeing.