Unless you’re eating it, modern paint poses no known health risks. (Pastelists and encaustic painters are more exposed and should follow special rules for handling their materials and breathing fumes.)

That, unfortunately, is not the whole story.

Many people think watercolors are somehow safer than oils. That is not true. The binders for oil paints are siccative oils. The major ones are linseed (flax seed), walnut and safflower oil, all of which are edible. Some people have a sensitivity to odorless mineral spirits, but if you’re not drinking them or bathing in them, the current consensus is that they’re harmless.

What can be toxic are the pigments, and they’re pretty much universal across all mediums. That includes tattoo inks, which are a toxicological risk to human health.

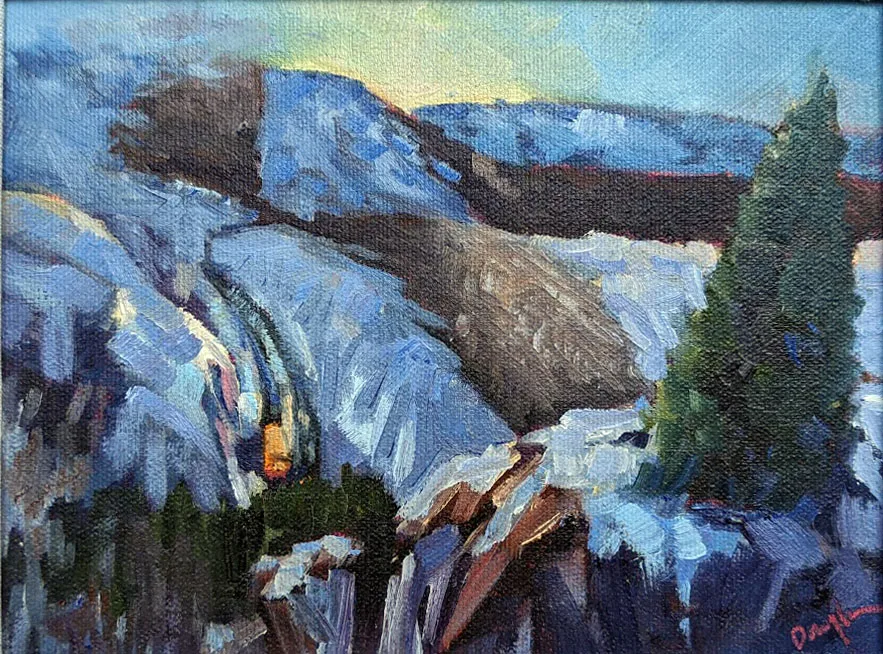

Making pigments is a messy business. Buffalo Color (formerly part of National Aniline and Chemical) manufactured pigments along the Buffalo River in my hometown, and pigment deposits remained along the shore as late as the 1980s. The photo above shows the condition of the river from Buffalo Color and Bethlehem Steel, now both gone.

Environmental legislation stopped wholesale polluters across a variety of industries in the US. That didn’t mean we weren’t still creating pollution; we just outsourced it to the developing world.

Cobalt, cadmium, and lead aren’t going to injure you as a painter, but they can injure the people who mine and refine them. Today’s emphasis is on mica, which gives us the glitter in makeup, car finishes and, yes, iridescent paints. Mica is mined in the US, but the top two producers in the world are China and Russia. India, the world’s eighth-largest producer of mica, is known to use child labor in mica mining.

Since the mid-1990s, pigment production grew quickly in mainland China and India. They are now the first and second producers of pigments in the world. The number one producer of cadmium? China. Of cobalt? Congo and China. Lead? China. Child labor is a real phenomenon in China; about 7.75% of children ages 10-15 work. So too is forced labor, using both minorities and prisoners. Congo’s child labor situation is more dire, with roughly 40,000 children in the cobalt mines, some as young as six. (The majority owners of these mines are Chinese.)

Cobalt, cadmium, and lead are all, to varying degrees, mutagenic (causes mutations), teratogenic (interferes with fetal development) and carcinogenic (causes cancer). In the modern world, we can’t avoid them entirely; for example, we need cobalt for lithium-ion batteries. But we can reduce our use of them where it’s less critical, and pigment is one of these areas.

For years, I’ve given my students a palette based largely on 20th century pigments, using the iron-oxide pigments as chasers. The one exception has been cadmium orange, because there’s still no reasonable substitute in oils; in watercolor, the quinacridone oranges are great. I’m not worried about my students; I’m worried about the children, involuntary workers, and those driven by poverty to work in unsafe conditions.

The 20th century pigments were developed first for the automobile industry, with other manufacturing applications branching out from there. Because they were intended to be used in American factories, they are safe, cheap, brilliant, and lightfast. In fact, they are far superior to their historical antecedents in almost every way.

Regardless of what pigments you’re using, waste should never be disposed of in our sewers or on the ground. For water-based paints, let the old paint water dry and put the residue in the solid-waste stream. For oil-based paints, let the solvent settle, pour off the clear liquid and reuse it, and let the remainder evaporate for disposal.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.