“I know it’s not done, but it’s where I stop because I’m afraid I’ll mess up what I have,” a student messaged me. She was painting in a plein air event where ‘unfinished’ and ‘overdone’ were both errors.

“I think you won’t mess it up, and you can always scrape back to this level if you do,” I replied. She was painting in oils, which have the advantage of a partial undo. In fact, that can be the resolution of many problems, because the average of your errors, revealed by scraping back, is often the right answer.

For most of us, figuring out when a piece is finished is an almost-intuitive process that varies from one piece to another. My answer is, “I’m done when I’m sick of working on it,” but that isn’t particularly helpful advice. There are, of course, some objective factors guiding me:

Intention: I often start with a specific idea for a piece. I’ll never realize that 100%, because the human mind has its own ideas. However, I want to know that I’ve at least made my point.

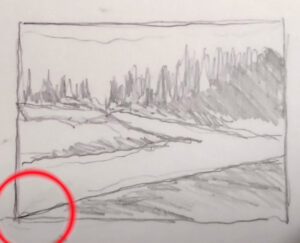

Composition: I’m a bear about understanding the composition from the very beginning. If I haven’t done that, no technique at the end can save the painting. That said, there may be adjustments needed to strengthen my original idea-darks restated, or brushwork softened or made more precise.

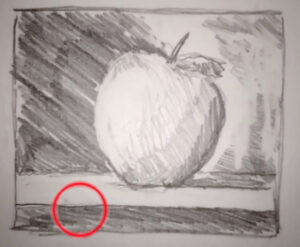

Technique: Have I built up my paint level to a satisfying conclusion? Is my brushwork fluid? Are there places of rest? Are there passages that just need more energy?

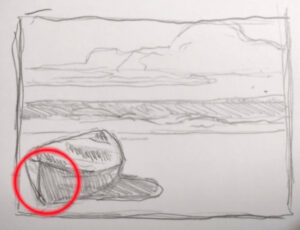

Emotional impact: This is a question that’s best asked in the design phase, but if I finish and it’s just meh, I might need to ask why. If it’s that I have no emotional connection with the work, I will scrape it out. However, sometimes the emotional impact of a piece is dampened by overworking passages, and that is something I can put right. In oils or pastels, I can scrape or brush out the offending passage. In watercolor the solution is usually to start again. The second version of a watercolor is often much looser than the first. (That’s one of many reasons to paint the subject in grisaille before you jump to color.)

My energy levels: I’m not superhuman. That feeling of exhaustion can be the signal that it’s time to quit before I do something stupid. Or, it just might mean I have to come back another day.

Feedback: I rarely ask for feedback, and then only from a very small cadre of fellow painters. However, you may feel you need critique. In the context of a class, that’s important: you should be open to new ideas. At a painting event, you run the risk of chasing back and forth trying to incorporate everyone’s comments into your work. That’s a sure-fire way to wreck a painting.

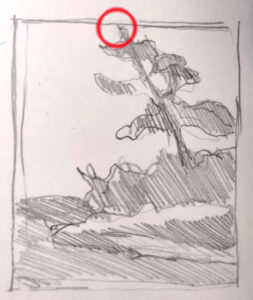

Personal Style: I’m usually a moderately-loose painter. That influences when I consider a work finished. You may be much more detailed and polished. While the technique remains the same, the endpoint differs. A person who is making a highly-detailed painting like Cooper Dragonette‘s fabulous painting of downtown Belfast, above, will take much more time getting the details right.

Deadlines: In some cases, I’m working against external factors like customer-dictated deadlines. I have always found that such deadlines sharpen my focus, but others may find them horrifying.

Endless revisions: Almost every artist has, at one time or another, had a painting in the studio that won’t leave. I’ve had a few of these, upon which I dabbled until flummoxed, only to pull them out again in six months to dabble again. For me, this never ends well; I might as well have tossed them at the beginning.

Ultimately, the decision about when we’re finished is highly individual. It involves technical assessment, emotional connection, and our own unique creative process. As we gain experience and refine skills (which we should do throughout our lives) that endpoint changes.

My 2024 workshops:

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.