“How do you paint water?” is probably the most common question I’m asked. It reminds me of that old joke:

“Where does an elephant sleep?”

“Anywhere he wants.”

Water is so immense, slippery, and mercurial, that it is impossible to nail it down into a schtick. And thank God for that.

Instead, the painter of water must rely on observation. Reflections are a distortion of the surrounding environment. That’s true whether you’re painting them on the ocean, or in a glass of water. These reflections are never going to be consistent but they will follow the laws of physics.

Imagine an ocean that is perfectly flat, and that you can walk on water. Looking at your feet, you can see straight down into the water. It’s not reflecting anything. Looking at a rubber ducky floating ten feet away, you’re looking at the surface at about a 26° angle. You’ll see a reflection of the ducky, the sky, and a glimpse of what’s under the surface. As you look farther away, the angle gets smaller and smaller, and all you see is the reflected sky.

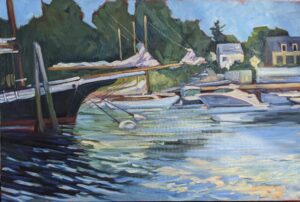

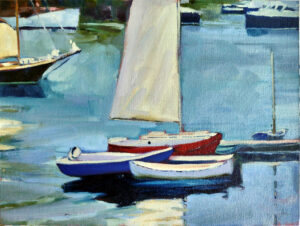

Reflection involves two rays – an incoming (incident) ray and an outgoing (reflected) ray. Physics tells us that the angles are identical but on opposite sides of a tangent. This is why the reflection of a boat needs to be directly below the real object in your painting. You can add other colors into that area, but the reflection can’t be wider than the object it’s reflecting.

Water is transparent, but it has a shiny surface. Some rays of light make it through and bounce back at us from the sea floor. Reflections in glass work the same way. You can see through the glass in the surface that’s facing you, but the curving sides reflect light from around the room. Because glass is imperfect, these reflections will be distorted.

The ocean complicates matters by being bouncy. Even on the calmest day, the surface of water is never perfectly flat; it’s wavy or worse, just like a fun-house mirror. Waves are a series of irregular curves. How they reflect light depends on what plane you’re seeing at that nano-second. It seems like the easiest thing to do is to capture it in a photo and paint from that, but what we see in photos is sometimes very different from what we perceive in life.

Instead, sit a moment with and watch how patterns seem to repeat. They’re never exactly the same, since waves are a stochastic process (think random but repeating). But they’re close enough to discern general patterns.

Solid objects can also trip you up in their reflections. Consider the humble spoon. It’s concave. That distorts its reflections. There’s no point in trying to predict what you might see; it’s best to just look. Likewise, a mirror only reflects straight back at you if you’re in front of it.

There are times when the ocean makes no reflection at all. Only smooth surfaces reflect light coherently enough to make reflections. That’s why burlap has no reflections. Sometimes, when water is being wind-whipped, it doesn’t have reflections either. To paint such a sea, keep the contrast low. A grey, windy day, or a turbulent sea will have a surface too broken up to reflect anything but the most general light.

It’s always best to paint the reflections at the same time you’re doing the rest of the painting, rather than adding them as an afterthought. They’re a fundamental part of the design.

Some people say that reflections should be lower in chroma than their objects, but I don’t think that’s true. Often, the ocean seems to concentrate color. Sometimes, the water will be lightest at the horizon; other days there will be a deep band there. However, the farther away, the more its colors shift toward blue-violet.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.