I’ve painted two paintings of spinning children’s rides, Best Buds, above, and Tilt-A-Whirl. Both were an attempt to capture something of the innocence of carnival rides and the warm summer days of our youth.

Occasionally, someone will question whether I did them from life, because they think it’s impossible to paint something spinning. It is doable, although it can be dizzying.

The Adirondack Carousel, which is the subject of this painting, is in Saranac Lake, NY. It features hand-carved woodland animals from the Adirondack Mountains. It was the brainchild of local woodcarver Karen Loffler and took twelve years, countless volunteer hours, and $1.3 million in locally-raised funds.

The result is indistinguishable in craftsmanship from the great carousels that were produced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet it’s distinctly local, and clearly beloved by children. John Deer, on the left in my picture, is a particular favorite. The kids told me so.

The pavilion has 24 handcrafted wildlife animals, eighteen of which are on duty at any one time. Do I have a favorite? How could I, when they’re all so perfect? (You can see them here.) I think the black bear, decked out in the colors of the Hudson’s Bay Company point blanket, captured my attention first. But each animal has its own particular charm-except maybe the black fly.

There’s a wheelchair accessible ride in the form of a Chris Craft boat. The overhead scenes of Saranac Lake were painted by local artists (including my friend Sandra Hildreth), as were the floral medallions. A local blacksmith made the weathervane and a local carpenter built the ticket counter. The building was painted and stained by volunteers. The result is distinctly local, happy, and very Adirondack.

The girl is a complete invention, vaguely reminiscent of a kid I knew in Maine named Meredith Lewis (who is now a willowy, beautiful teenager). I debated on the title for quite a while, finally settling on Best Buds. Even if my girl is riding the otter, her heart belongs to John Deer.

Best Buds is oil on archival canvasboard, 11X14 and is in elegant Canadian-made frame with wooden fillet. It lists at $1087, but you can have 10% off it (or any other painting) by using the code THANKYOUPAINTING10.

My 2024 workshops:

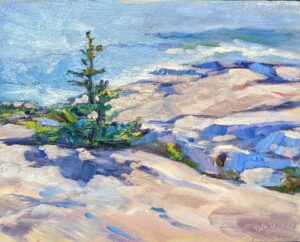

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

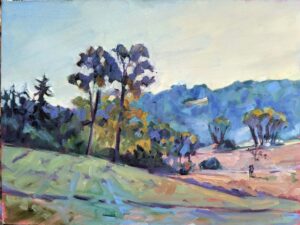

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

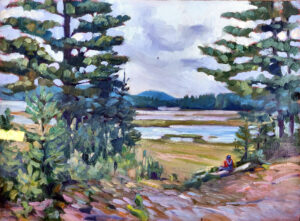

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.