How dare anyone lecture Emily Carr—even posthumously—on relations with her indigenous neighbors?

|

|

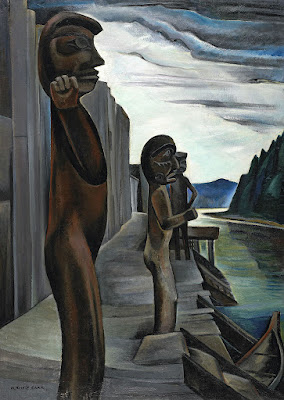

The Indian Church, 1929, Emily Carr, courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario. Lawren Harris once owned this painting.

|

Canadians are a mythically polite people. That reputation has at least some basis in fact. Why else would they rename Emily Carr’s iconic 1929 painting Indian Church as Church at Yuquot Village?

Georgiana Uhlyarik, of the Art Gallery of Ontario, told CBC Radio that the former title contained “a word that causes pain.” (Uhlyarik is not indigenous herself.) I’m not certain why it should be a painful word. If anything, ‘Indian’ is an indictment of our ancestors, not the people it was applied to. Emily Carr named her painting in the common parlance of her day.

Carr was always sympathetic and knowledgeable about the native people she painted. In her lowest days she made pottery for sale to tourists. “I ornamented my pottery with Indian designs — that was why the tourists bought it. I hated myself for prostituting Indian Art; our Indians did not ‘pot,’ their designs were not intended to ornament clay — but I did keep the Indian design pure.

|

|

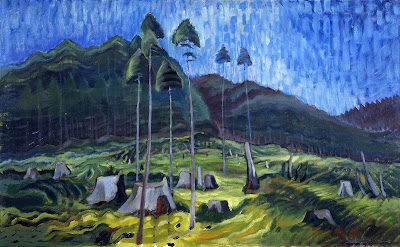

Blunden Harbour, 1930, Emily Carr, courtesy National Gallery of Canada

|

“Because my stuff sold, other potters followed my lead and, knowing nothing of Indian Art, falsified it. This made me very angry. I loved handling the smooth cool clay. I loved the beautiful Indian designs, but I was not happy about using Indian designs on material for which it was not intended and I hated seeing them distorted, cheapened by those who did not understand or care as long as their pots sold,” she wrote.

Carr was born in Victoria, BC, in 1871 to English parents. She studied art at the San Francisco Art Institute and in London. By the turn of the century she was already focusing on her subject: the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest. But it was not until she visited France in 1912 that she would marry that subject to post-impressionism.

|

|

Kitwancool, 1928, Emily Carr, courtesy Glenbow Museum

|

Her personality was too uncouth to be a good teacher, and her work was too distinctive to sell easily. She struggled to find a business model that worked. Failing, she traveled north to the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) and the Skeena River, to document life among the Haida, Gitxsan and Tsimshianpeople.

Carr documented the art of the Pacific Northwest with anthropological precision. “These things should be to us Canadians what the ancient Briton’s relics are to the English. Only a few more years and they will be gone forever into silent nothingness and I would gather my collection together before they are forever past,” she said.

Public response remained dismal. Carr returned to Victoria to run a boarding house, doing almost no painting. She grew fruit and vegetables in her backyard and raised chickens, rabbits and bobtail sheepdogs for sale.

She was middle-aged when she was finally ‘discovered’. After a visit to her studio in 1926, anthropologist Marius Barbeau wrote to Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada, suggesting that the Gallery purchase her entire collection. Brown was cool to the idea until he visited her studio during planning for a show entitled Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art – Native and Modern.

|

|

Odds and Ends, 1939, Emily Carr, courtesy Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. In later life, Carr began to focus on pure landscape and environmental issues.

|

Brown selected twenty-six paintings and hooked rugs and pottery for the exhibition. He suggested that Carr read Frederick Housser’s A Canadian Art Movement, introducing her to the Group of Seven. He also gave her a complimentary rail pass to get to Ottawa for the opening.

On the way, she visited A. Y. Jackson’s studio in Toronto. “I felt a little as if beaten at my own game. His Indian pictures have something mine lack — rhythm, poetry. Mine are so downright. But perhaps his haven’t quite the love in them of the people and the country that mine have. How could they? He is not a Westerner and I took no liberties. I worked for history and cold fact. Next time I paint Indians I’m going off on a tangent tear. There is something bigger than fact: the underlying spirit, all it stands for, the mood, the vastness, the wildness, the Western breath of go-to-the-devil-if-you-don’t-like-it, the eternal big spaceness of it. Oh the West! I’m of it and I love it,” she wrote.