Frederic Edwin Church’s Heart of the Andes is a monumental work in every sense of the word. At 10 feet wide and 5.5 feet tall, it takes up an entire wall in the Met. It’s intricately detailed, but that is not what makes you suck in your breath when you first see it. It’s the sheer audacity of the work, its scale.

Imagine the response at its unveiling in April, 1859 in New York. In a massive, theatrical frame that increased its breadth and height, it was artificially lit in a darkened chamber. An epic success, it drew 10-13,000 viewers a month, each shelling out 25¢ for the privilege. (Church went on to sell the painting for $10,000, setting a record for the highest price ever achieved by a living American artist. Yay, Church!)

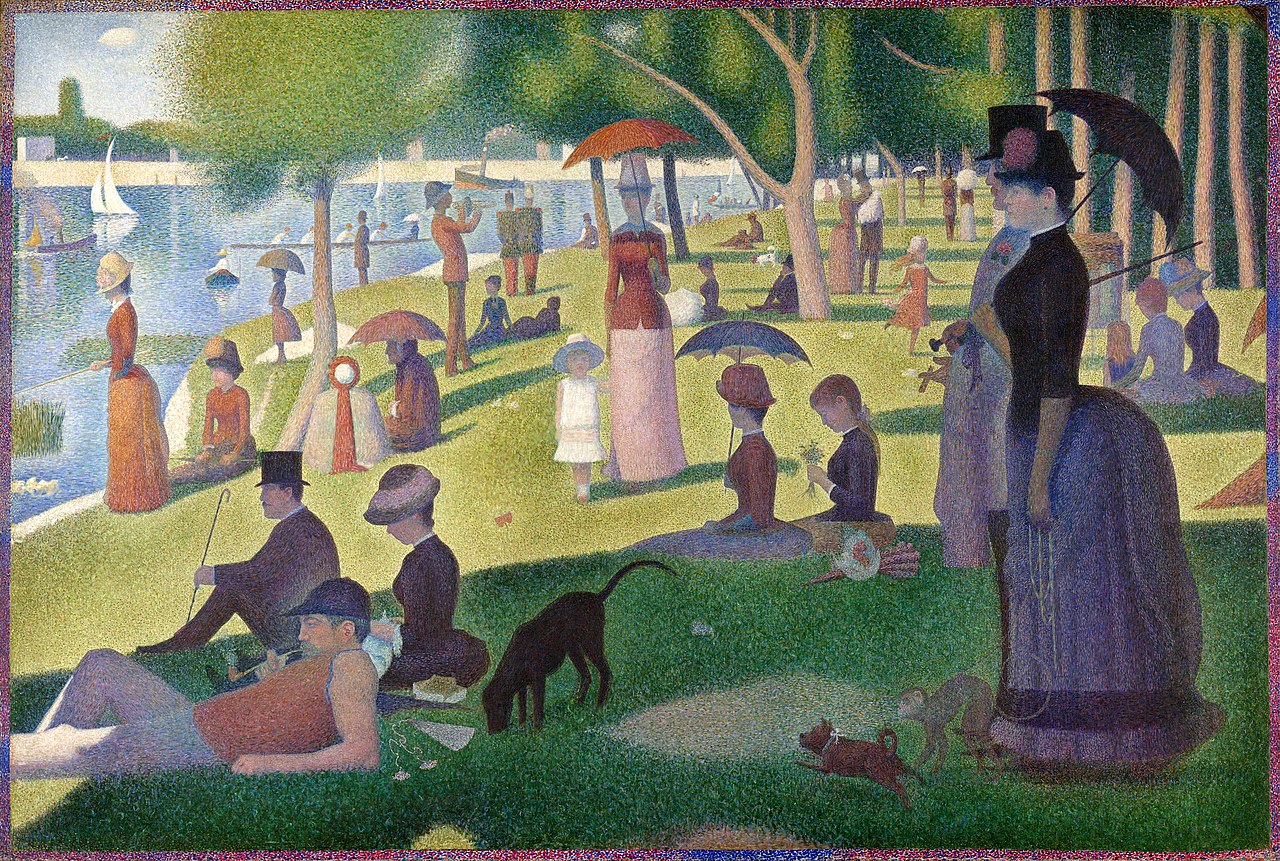

And yet, if you’ve only ever seen it on your computer screen, it looks-well, meh. It’s a lovely example of the picturesque, that English ideal of beauty, but it’s hardly moving. It’s only when you experience it in person that you begin to understand what the excitement was all about.

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch is even more colossal, at about 14 feet wide by 12 feet high. The Rijksmuseum published a 44.8 gigapixel image of it in 2020, right after it was restored. I’ve crawled over that image. It allows me to get closer to the painting than I ever could to a ‘live’ Rembrandt. But what it can’t do is give me the sense of scale of the actual painting. I’ve been to the Met innumerable times, but, alas, I’ve never been to Amsterdam.

How we see

Humans have tunnel vision compared to other animals, but our peripheral vision is still important. It is not acute, and it gets worse as we get to ‘the corner of our eye’. Peripheral vision helps us perceive sudden changes, like cars veering into our lane of traffic. More importantly, we ‘know’ what’s happening in our peripheral vision because we know what the images on the edges ‘mean’ without needing to focus on them. Our brains interpolate and fill in the information. When they can’t, we turn our heads and figure it out. It’s an irresistible impulse.

When we look at a painting in real life, we’re using every part of our visual field-both the focus and the periphery. We flick through the painting’s focal points with our tunnel vision, just as we would flick through a natural scene. That gives us a sense of reality. That’s far different from when we look at a painting on a screen, especially when the screen is tiny, as on our phones. Then we’re just seeing it with our narrow tunnel vision. We lose the spatial sense that our eyes are designed to use.

That’s not even considering the color inaccuracies and loss of detail that are inevitable in photographs. Large canvases can look overworked and stilted in photographs even when the brushwork is lyrical in real life. A small photo reduces brushwork to an afterthought.

The 21st century artist must constantly think of his work in relation to the small screen, in addition to its real-life appearance. In some ways, that’s healthy, because it drives good composition. But it does change our approach to painting. How would Monet’s Water Lilies series have turned out had he had one eye on our phone screens?

I love living in a time where I can tour the world’s museums at a click of a mouse, but that should never be confused with the tactile experience of paintings.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

This brings up the question: what’s the difference between a painting and a mural? Is it merely that the mural is painted in a wall?

Finally, a question I can answer! A mural is any piece of two-dimensional artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. That includes fresco, mosaic, graffiti and permanently affixing a painted canvas. The definition isn’t about the size, but the substrate.