Each week until the end of the year I’ll be giving you a behind-the-scenes look at one of my favorite paintings. These are paintings that are available for you to purchase unless otherwise noted.

This is a portrait of lost time, both my own and my hometown’s. I was born in North Buffalo in 1959; I lived with my grandmother in South Buffalo for my last year of high school. My bus ride took me down South Park Avenue past the notorious Commodore Perry Projects, right through the First Ward where the rebranded Silo City is located. That’s on the verge of being hip, and a state park has made the grotty old waterfront into something beautiful. The nearby area now called Larkinville is a true success story. Restaurants, offices, shops and condos now fill an area that was once a terrifying post-industrial, apocalyptic wasteland. I don’t miss it a bit.

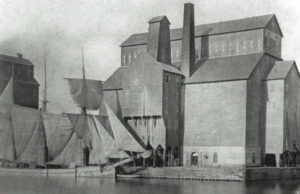

Buffalo was built on the back of the grain elevator. It was invented there by Joseph Dart and Robert Dunbar in 1842-1843. Before that, grain was handled in bags, which were wrestled off lake freighters (schooners and brigantines) and moved to canal boats to head down the Erie Canal. Dart and Dunbar’s elevator scooped loose grain out of the holds of the boats and lifted it to the top of a tower. It could then be dumped directly into canal boat or rail car, oldest product first. Think of it as the earliest example of cross-docking.

At the start of the 20th century, Buffalo was the fifth-largest city in the US and the largest grain port in the world. Much of the grain harvested in the Midwest was shipped through Buffalo. Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence Seaway are separated from the other Great Lakes by Niagara Falls, which meant that lake freighters couldn’t go any farther east than Buffalo.

That problem wasn’t really solved until 1932. The Fourth Welland Canal meant grain could just float right out from Minnesota to the Atlantic Ocean and beyond. That was the death-knell for Buffalo’s grain elevators, although their demise was slow.

My uncle Bob had a job as a night watchman in Silo City when he was a college student. Whenever I waxed lyrical about the elevators, he talked about the rustle and squeak of thousands of rats along his beat. Uncle Bob and my husband and I canoed up the Buffalo River once. It was completely industrial, with Pratt & Lambert still dumping pigments into the water.

The siloes still crowd the river on both sides, but they’re mostly empty now, a decaying reminder of the past. Only the General Mills elevator still accepts freighters, because they’re still manufacturing in Buffalo.

Buffalo loves its grain elevators but can’t quite figure out what to do with them. I feel exactly the same, but I’m a landscape painter. I painted the view from the Ohio Street Bridge. That’s the Standard Elevator on the left, and the Electric Elevator and Perot Malting on the right.

My challenge was to illustrate the worn surfaces of the elevators from a distance. I like cold wax medium. It can be brushed or troweled on, depending on how it’s thinned, and it can be burnished, scraped, sanded, or abused in a million different ways once it’s in place. I used it in the sky, applying it in thin, pigmented layers, and then buffed and burnished it so it had the character of the elevators’ own old brick walls.

That’s the Buffalo of my youth, but it’s not the Buffalo you’ll see today, much of which has had a facelift in the ensuing decades. “The reuse projects are really cool but they’re only cool in light of where the city is coming from,” a Buffalonian told me.

Last week I wrote about how you can’t go back and recapture lost memories. This painting is of something that still exists, but in a city that has changed beyond all measure. It’s 18X24, in a handmade cherry frame, and it’s available for $2318. It’s a bargain compared to what an historic elevator will cost you, and sized to fit in a living room to boot. Click here to purchase online.

My 2024 workshops:

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.

Paintings (and poems!) do capture memories, but you’re right, you have to capture them while they live . . . but, captured, they live and live and live, just moments of them, as fresh as can be. Love the elevator; the sky calls attention to the rugged past of it. Also the flowers by Patricia Harrington from earlier in the week!

(little bear’s howard)