Don’t fall into the trap of drawing what you know instead of what you see.

|

|

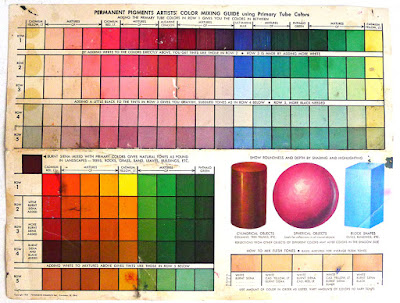

The Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874, Claude Monet. All three waterlines are parallel to the horizon.

|

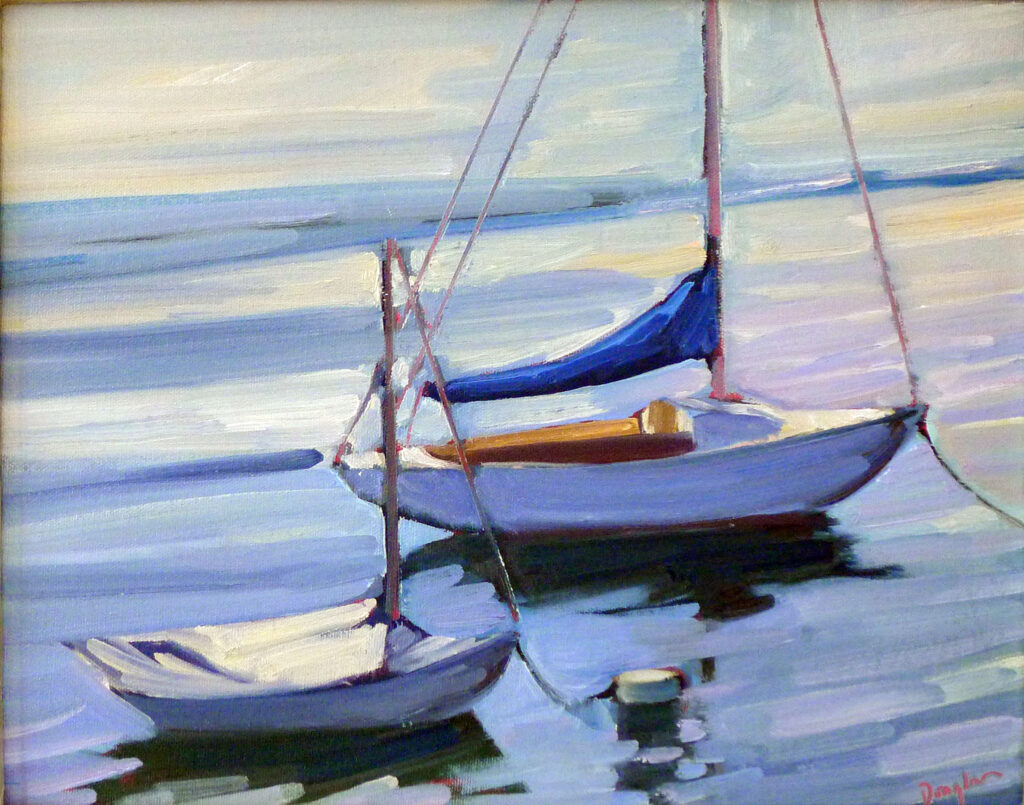

I prefer painting from a floating dock, where I’m at eye-level with the boats regardless of the tide. However, on Friday, I found myself up on the wall

looking across Camden Harbor. That creates a different perspective.

The horizon line in a drawing is the viewer’s eye level, regardless of where the viewer is standing. At the top of Mount Rainier, your horizon line is around 14,410 feet above sea level, and everything is below you. If you’re swimming in the Caribbean, your horizon line is about three inches above sea level and everything but the sharks are above you.

I explained basic perspective in

this post about drawing clouds; the exact same rules apply to boats, except that everything is flipped over. We can see down into objects that are at our feet, but not into objects at the same level that are far away. The farther away the object is, the more horizontal our gaze is as we look at it. Our measly 5 or 6 feet in height is nothing compared to the distance across.

When a boat is a few hundred feet away in the water, it’s for all intents and purposes at eye level. Its waterline is almost absolutely flat, regardless of whether you’re looking at its side, transom, or bow.

|

|

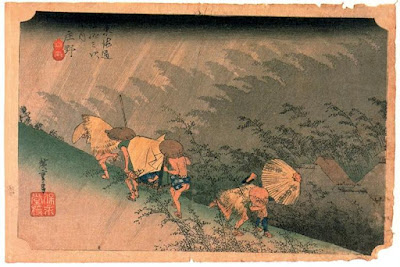

The Seine at Argenteuil, 1872, Alfred Sisley. Although it’s also from towpath height, Sisley included more foreground, creating the sense that we are looking down into the Seine.

|

During the 1870s and 1880s

Argenteuil, northwest of Paris on the Seine, became an important painting location for the

Impressionists. They immortalized its bridges and boats from every conceivable angle.

We can infer Monet’s point of view in the top painting as being about equal to the house across the river. In other words, he was standing on a towpath. That allows us to see into the boat slightly, as we’re at mast height to it and it’s close to the near bank. We cannot see into the far boats at all. Note that the far bank and the waterlines of the far boats are parallel to the horizon. The bridge, which reaches across the river to us, is not.

Alfred Sisley’s painting is from the same height, but he’s given us more foreground, and therefore the sense of looking down into the water. But while the tree in the river is definitely below us, the boats are not. Again, their waterlines are parallel to the horizon. The river bends, and the land curves away, but the curve is very gradual.

|

|

Boating, 1874, Édouard Manet. Here we’re looking straight down into the boat from impossibly close quarters.

|

We are definitely looking down into Édouard Manet’s pleasure boat in his 1872 painting done on the same river. Manet has us practically standing on the rail looking down into the well of the boat. The horizon isn’t even visible. It would be yards above the boaters’ heads.

|

| An example of incorrectly drawn boats. |

Ignoring these rules results in the most common error I see in painting boats. This is from an example I picked up on the internet. The boats are close to the horizon but we still seem to be looking down into them. In fact, the closest boat is at about the angle of Manet’s Boating. This is an impossibility, as the three masterpieces from Argenteuil have demonstrated.

This happens frequently with painters unaccustomed to boats. I think it is a case of painting what we think we know vs. what we see. We know that boats have form, therefore they must have perspective, too. Well, they do, but it’s very subtle from the distance we usually see them.