“Who are your favorite painters?” a reader asked. That’s an impossible question. Instead, here are some painters who I profoundly admire and you should too.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder was the most significant of the Dutch/Flemish Renaissance painters. Among the first generation to paint other than religious scenes, he was a great landscape artist. His paintings, especially genre paintings, are a whirl of human activity. But what I admire the most is his ability to hide the focal point, or multiple focal points, in insignificant corners of his paintings. His figures are as fresh and realistic as when they were painted.

Albrecht Dürer was a great painter, but I admire his engravings, woodcuts and drawings most. He was a superlative draftsman, particularly in perspective. It’s his simple, profound understanding of the Passion that moves me most. He did at least three versions, and they’re the visual equivalent of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion.

Peter Paul Rubens may have been intellectual, classically trained, and the favorite painter of the Counter-Reformation, but to me, he’s the progenitor of comic-book art. I draw a direct line between his dynamic canvases and the work of the late Steve Ditko. Both dealt with cosmic issues in a restless, complex way.

John Constable is best known for his great set-pieces like The Hay Wain, but he is also the (largely uncredited) inventor of modern plein air painting. In place of a classical education, he spent his youth wandering the fields of his native Essex. This “made me a painter, and I am grateful,” he said. By the time he convinced his father to let him study art, the damage was done—he was a fresh, observational painter in an age when classicism was king.

Édouard Manet is known as a pivotal painter in the transition between Realism to Impressionism., but his importance to me is his surface treatment. He was the first painter to eschew sparking bright lights and a superlative finish in favor of his own, raw, handwriting. He is, in this sense, the father of Modernism.

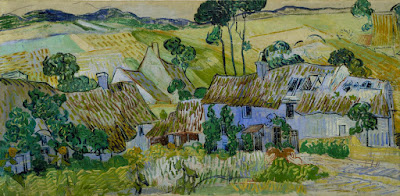

Vincent van Gogh hardly needs any introduction, being one of the most influential painters in art history. His importance to landscape painters can’t be overstated. He was the precursor to Fauvism, and that, far more than Impressionism, is what speaks to our own times.

Tom Thomson and the Group of Sevencame into being across Lake Ontario from my hometown of Buffalo, but I didn’t really learn about them until adulthood, since realism was so out of favor in my youth. Still, these painters did more than any others to apply the principles of Impressionism to the North American landscape. They vary greatly in style, but they were united by their love of the Great White North and the wilderness. They were intrepid extreme plein air painters.

Rockwell Kent was eulogized as “a thoughtful, troublesome, profoundly independent, odd and kind man” by the New York Times. That’s all true, but he was also terrific painter, aggressively simplifying his subjects to their essence. His subjects—concentrating on the Adirondacks, Alaska and Monhegan—are all about the ever-changing light of the north.

Lois Dodd could be admired just for her tenacious success in the male-dominated New York art scene. Her credentials are as sterling as any of her male peers, but she had her first career museum retrospective in 2013, when she was already in her eighties. That would mean nothing if she weren’t also a superlative, self-directed painter. She ignored Abstract-Expressionism and Pop Art to forge her own, realistic way.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.