Stop looking for something brilliant to say; it’s not about you.

|

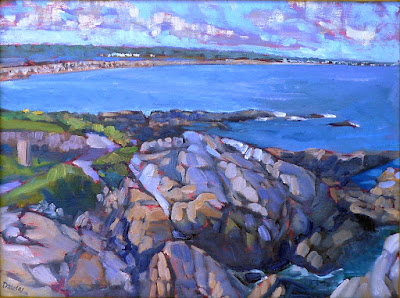

| Ogunquit, by Carol L. Douglas |

My friend likes to make “medieval” artwork through her persona in the Society of Creative Anachronism. If any activity ought to be about pure fun, this is it, but she recently told me about a terribly harsh criticism she received on Facebook. She hadn’t asked for advice, but she got it anyway. The message she heard wasn’t about something she could do better. It was that this so-called expert was a cruel jerk.

In general, this is my rule for critiques over the internet: don’t. Comments are irrevocable once they’re out there in cyberspace. Your tone can’t modify or soften your words. You can’t really see the work, and while a thumbnail may tell you a lot about composition, it is silent about paint handling, mark-making, and scribing.

|

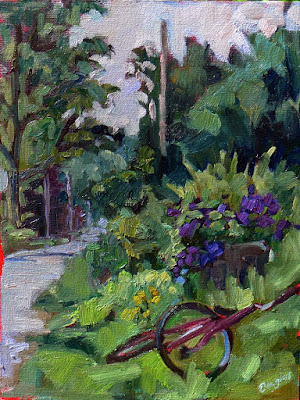

| Historic Fort Point, by Carol L. Douglas |

When I am asked for a comment, I talk about what I admire, reserving more thoughtful critiques for my classes and workshops. However, someone will occasionally press and want more specific criticism. At that point, I take the conversation to private messaging or email. It’s too easy for public internet conversations to devolve into a cruel pile-on.

We use the “sandwich rule” in our class. We begin by pointing out something the person did well. We then discuss what might have been handled differently. We finish by pointing out something else that the person did well, so that each session ends on a positive note.

|

| Lunch break, Castine, by Carol L. Douglas |

This method has been mocked as “fluffy bun—meat—fluffy bun,” but that misses the point. Most people are all too aware of their failures and not aware of their strengths. Their own self-doubt gets in the way of seeing what is successful in their painting. That needs articulation as much as the negatives do.

St. Paul was one of the most influential people of antiquity. Philippians 4:10-20 reveals a teacher who is affirming, content, flexible and confident. He exhorts, he talks freely of his own challenges, and he’s optimistic. That’s a great model on which to base teaching and criticism.

People are capable of wonderful things, but our society routinely discourages us from daring to be great. When someone disregards all the voices telling them they can’t do something, and they challenge themselves with hard work and dedication, they ought to be encouraged.

| Kaaterskill Falls, by Carol L. Douglas |

I’m up at Schoodic Institute teaching my Sea & Sky workshop. On Thursday evening, we’ll have a critique session. This isn’t about learning what’s wrong with our paintings. It’s also about learning to read artwork and learning to write artwork that is readable. To this end, we’ll ask some general questions, such as:

- “What do you notice first? Second?”

- “Why did you see those things in that order?”

- “Does this evoke a feeling or response in you?”

- “What is the point of this work?”

Frankly, there’s enough negativity in this world. If we err, let us err on the side of kindness.