Think of it as getting a painting lesson from the masters.

|

|

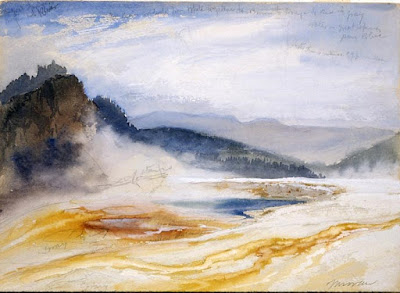

Great Springs of the Firehole River, by Thomas Moran, 1871, is one of the paintings my students will be copying this week. Courtesy National Park Service. |

If you visit art museums regularly, you may have seen students set up to copy masterpieces. Or, you’ve seen copies made by great artists of other artists’ work. What were they trying to accomplish?

Vincent van Gogh admitted himself to the Saint-Paul asylum in May, 1889. He painted around 150 canvases there, including the iconic The Starry Night. He also made about thirty copies of masterworks of others.

“I started making them inadvertently and now find that I can learn from them and that they give me a kind of comfort,” he wrote. “My brush then moves through my fingers like a bow over the strings of a violin – completely for my pleasure.”

|

|

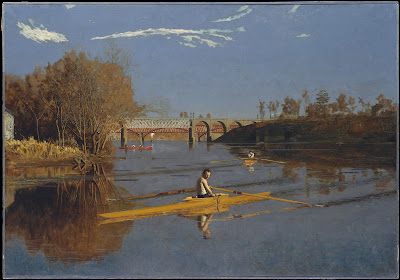

The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull), by Thomas Eakins, 1871, is one of the paintings my students will be copying this week. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum. |

Copying masterworks is a time-honored way of learning, both in western traditions and in others. Transmission by Copying is one of the six principles of Chinese painting laid down by the Chinese art historian Xie He in 550 AD.

“Nobody is born with a style or a voice. We don’t come out of the womb knowing who we are. In the beginning, we learn by pretending to be our heroes. We learn by copying,” wrote Austin Kleon.

|

|

The Pine Tree at Saint Tropez, by Paul Signac, 1909, is one of the paintings my students will be copying this week. Courtesy Pushkin Museum. |

Copying is a way to study and evaluate a painting that’s far more immersive than simple looking. It enables us to understand another artist’s process. It forces us to consider what we find admirable in art in general. And it teaches us brushwork.

Most importantly, it sets aside our own need to tell a story. That liberates us from the frustration of our own limitations. We can concentrate on composition and color instead of being fully engaged in the problem-solving of unique subject matter.

It makes sense to copy works you admire. If you’re drawn to the paintings of the Canadian Group of Seven, don’t copy a Titian. You’re going to be paying a lot of attention to the painting you copy. It should be something you really love.

Today, we have a technical advantage over Van Gogh, locked up as he was. We can easily retrieve high-quality images from the internet. Many museums even have scalable images on their websites.

You must be able to see the brushwork to fully immerse yourself into the work. (Of course, if you’re copying a linear painter like Bronzino, there may not be much visible brushwork to copy.)

|

|

Woman with a Parasol, Turned to the Left, by Claude Monet, 1886, is one of the paintings my students will be copying this week. Courtesy Musée d’Orsay. |

What you can’t see on the internet is the dimensionality of the painting, its impasto, so that is one area where you’ll have to interpolate.

“I was surprised at how small the Mona Lisa is,” is a common sentiment about one of the world’s most-copied paintings. It’s important to know how large the work you’re copying is, even if your copy is going to be very small. The brushes appropriate to a massive painting are not appropriate to a miniature, and that will affect your interpretation.

Mona Lisa shows that paintings can undergo significant changes through restoration, fading, or the appearance of pentimenti. She once had eyebrows and eyelashes and was lighter in color; all those changes have occurred in the 500 years since Leonardo set down his brush. That doesn’t mean we can’t learn from copying her, but it’s something we should be aware of.