Some people are “just born with talent”

One of the most pernicious lies about art is that people are either born with innate talent for art, or they’re not. While some people may show early aptitude, art is a skill that requires practice, dedication, and continuous learning. I’ve taught for a few decades now, and some of the people who’ve gone the farthest would surprise you.

The starving artist

The ‘starving artist’ is a fiction of popular culture. As in every entrepreneurial career path, there are people who will be successful and those who won’t. Some will work second jobs to support their families, but I know many people surviving and prospering as artists.

Artists are loners

Art is communication, and the people who do it have something to say. While some need solitude, many collaborate and work best in social settings. Online groups, workshops, cooperative studios, and classes provide social opportunities and support for solo artists.

Art is not a “real” job

At the end of 2021, the arts and cultural sectors made up 4.4% of the nation’s economy. That was more than a trillion dollars. Between 2020 and 2021 the economic value of the arts grew by 13.7%, a disproportionately large increase when compared to the wider economy.*

Oil paint is toxic

The binder for oil paint is linseed oil, which comes from flax seed. That’s the same stuff I put in my oatmeal every morning. The pigments in paints can be toxic, but it’s easy to choose a non-toxic palette these days.

[Fill in the blank] is the easiest medium

Every medium has some maddeningly difficult technical issues and things that are easier than in other mediums. In the end, they balance each other out pretty evenly. And, anyway, once you get past the question of how to get the paint where it belongs, most of the difficulties of painting are true across all media.

Art is easy

Creating good art demands dedication, practice, and continuous improvement. It’s not merely about inspiration striking; good artists put in years of effort to develop our skills.

There’s an ‘arty personality’

Probably, but that person is probably a poseur. Most working artists are no different from their neighbors. You might actually be living next door to an artist and not even realize it.

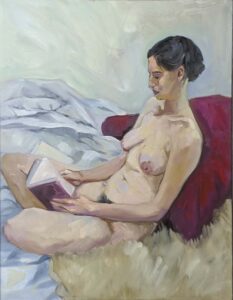

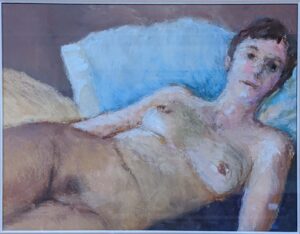

Figure is the highest expression of painting

Artists used to believe in a hierarchy of genres, but that ship has sailed. Done well, all styles and genres have their value and their challenges. Often the simplest work is, paradoxically, the most difficult.

Art doesn’t require education

There are excellent self-taught artists, but they’ve spent a lot of time studying others’ technique. Artistic practice rests on two millennia of technical skill, carefully passed along from masters to students. You don’t learn that by just thinking about art.

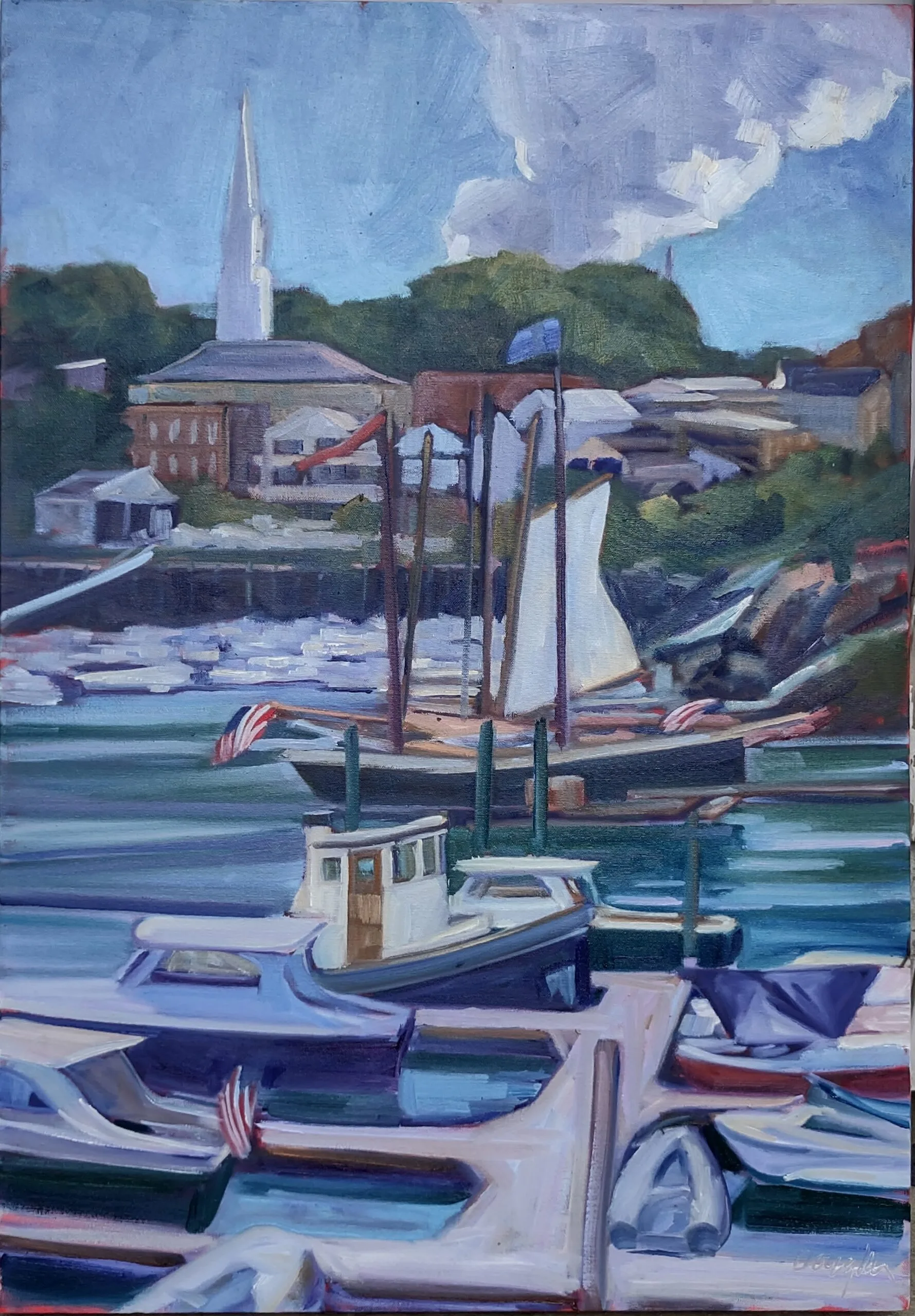

My 2024 workshops:

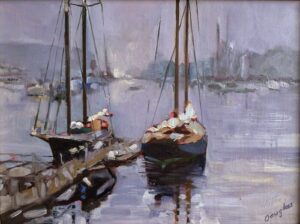

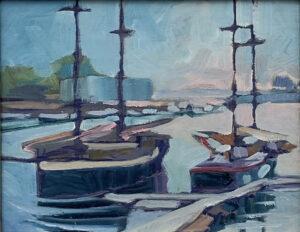

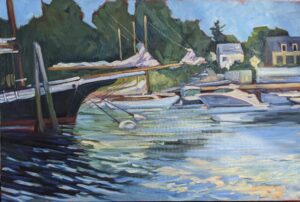

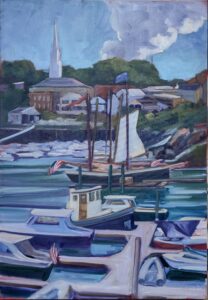

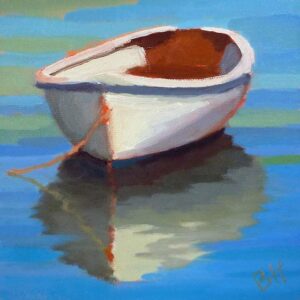

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

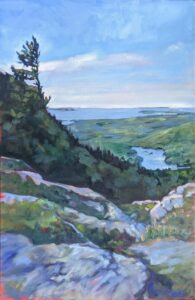

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

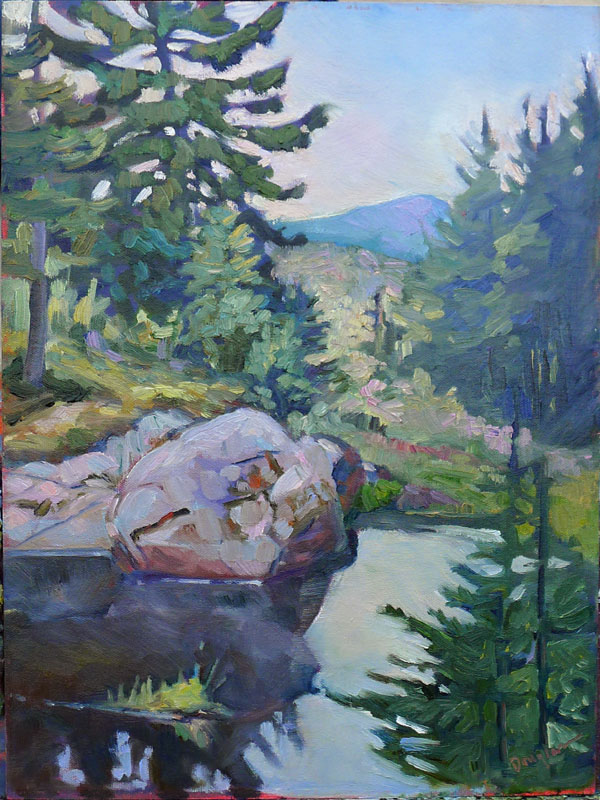

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.