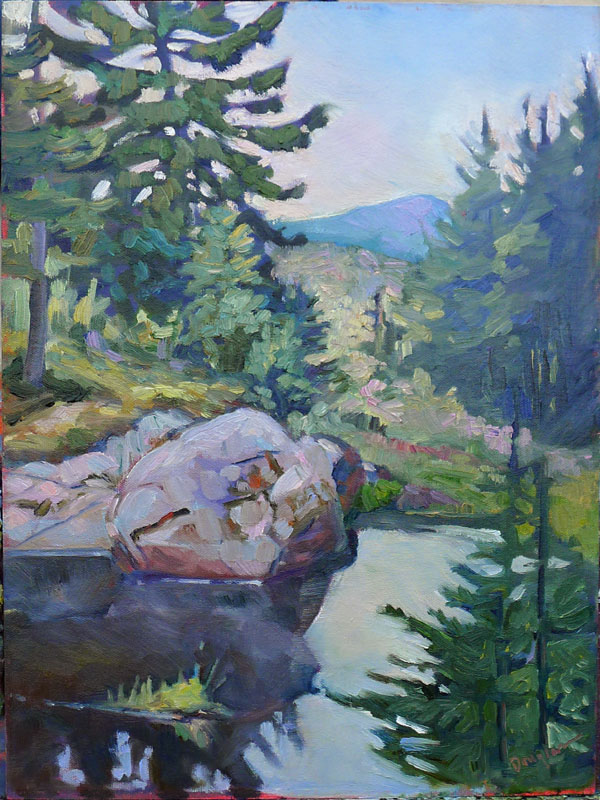

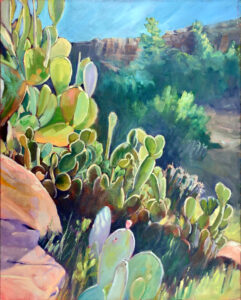

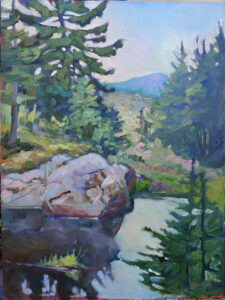

A well-known western painter sent me three images: her own reference photo, her watercolor, and a copy made by another artist. The copier had posted it on social media, cheerfully outlining her process with no hint of credit to the original artist. “She even copied my mistakes!” sputtered my correspondent.

Luckily, this resolved without lawyers. When challenged, the infringer agreed to take the work down and never sell it. That’s the only reason I’m not calling her out here.

Is it OK to copy artwork?

My correspondent was right in not asking the infringer to destroy the work. It’s legal to copy other work. It is illegal to sell, publicize or publish that copy without permission from the copyright owner.

Many artists over time have copied others’ work, including Vincent van Gogh in his time in the asylum. This is a way to deeply engage with the original artist’s technique and intentions. Many teachers-including me-set our students to copying masterpieces. But this is a learning exercise only, and the work is never intended to be shown or sold, even when the original is out of copyright.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder churned out several copies of his own Massacre of the Innocents. It must have been very popular because his son made more copies of it. That made perfect sense at a time when the only way to reproduce a painting was to copy it brushstroke by brushstroke.

But that was then, and this is now. Copyright in the US is strict and enforceable. It’s there to protect creators, but, equally, you don’t want to get on the wrong side of it.

What is copyright?

Copyright is an inherent state that occurs at the time the work was created; registering it just provides one form of legal evidence that you created the work. For visual artists, registering every painting or photograph would be absurdly expensive and unnecessary; you would only do it if you needed to sue someone.

That means any photo or illustration you find in books, magazines, newspapers, and even on the internet is automatically protected by copyright law.

Protect yourself

The best way around this is to take your own reference photos. That’s important for more reasons than just copyright, starting with the greatly-expanded understanding we all have of places we’ve been to and people we’ve known.

Sometimes that’s impossible. You’re on the other side of the country or the boat has sunk. If a client sends you their own photo for a painting, you can presume permission. If it’s not their own photo, do some investigating. “He said he got the photo from his cousin,” is no defense.

If you use a third-party’s photo, protect yourself by obtaining written permission from the photographer.

You can use photos that are in the public domain. Copyright expires when the original creator has been dead for more than seventy years. Just google “public domain images” and the word for which you’re searching, like “clouds” or “Grand Canyon.” Creative Commons is an excellent source for public-domain images.

What if someone copies your work?

What if it’s your work being copied without permission? My correspondent contacted the infringer and asked her to withdraw the painting from the marketplace. She could have done this more formally through a cease and desist letter, but it turns out that she’d done all that was necessary.

If the infringer doesn’t agree to take the work down, it’s time to call a lawyer. In the US, copyright holders can sue content infringers for damages. Hopefully, it will never go that far, but it’s nice to know you have that tool at your disposal.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.