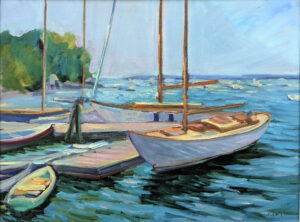

I’ll be painting next weekend in Camden on Canvas. I’m a little rusty because my time right now is being taken up by things that have nothing to do with painting. While I can’t go out and do a full plein air painting, I’m taking an hour a day to practice. These little ditties have no higher-level thinking and the subject is unimportant. For example, yesterday I painted a basket of beach toys.

I don’t worry about finishing these sketches. To paint like that occasionally is a relief, for style can be a trap and a delusion.

A reader told me yesterday, “My goal this summer is to get closer to a point of view and/or style.” I’m all for understanding point of view; it’s the deepest discipline in painting (and life). But style is something that should develop naturally. Forcing it stymies development.

Style is the mark-making, composition, color palette and other attributes in a finished work. Style ties an artist’s work together in one body, and it ties that artist to a specific time and place. It’s the art historian’s best tool for classifying artwork.

I can never be a Scottish colourist, any more than I can be Wayne Thiebaud. We’re each tied to our own specific moment. Imitating the style of Dead Masters is a sure path to irrelevance (while copying them is a great learning technique).

Great painters choose beauty over stylishness, even to the point of seeming awkward to their contemporaries. The difference is depth and staying power. It takes some scratching to get down to fundamental truth.

A good artist investigates thorny questions, not just about the world, but about painting itself. When they are answered, he moves on, just like Omar Khayyam’s moving finger. Often, by the time we get through the cycle of making and mounting a body of work, we’re no longer that interested in it. We’ve moved on to another struggle.

Each time we pick up the brush, there’s variation in how we approach painting problems. I might use a palette knife for a sky, even though palette knife painting is not part of my regular repertoire. I’ll occasionally revert to painting the way I first learned, with lots of detail and modeling. I refuse to box myself in by saying that a technique is inappropriate because it isn’t my style. ‘Embracing your style’ is a trap that painters may not be able to escape.

There’s a difference between style and being stylish. I enjoy Olena Babak’s ability to describe reflections in a single, fluid brush line. That’s not styling; it’s self-confident skill that results in stylish brush work.

Sometimes, what people call style is just technical deficiency. For example, some painters separate their color fields with narrow lines—white paper in watercolor, dark outlines in oils. I’d like to know that they embraced this voluntarily, not because they never learned how to marry edges.

I do not admire painters who use the same scribing or pattern-making on the surface of every painting. It’s style for its own sake, and it often is just a ruse to cover up badly-conceived paintings.

Mature artists don’t generally think about style. At that point, style is the gap between what they perceive and what comes off their brush. That’s deeply revelatory, and it can be disturbing when we see it in our own work.

Some of us try to cover that up with stylings, not realizing that those moments of revelation are what viewers hunger for. They—not the nominal subject of the piece—are the real connection between the artist and his audience.

Brilliant!

This is the right webpage for anyone who hopes to understand this topic. You realize so much its almost tough to argue with you (not that I actually will need toÖHaHa). You certainly put a brand new spin on a subject that has been discussed for many years. Excellent stuff, just wonderful!