In our impecunious youth, bar owners were notorious for offering bands the ‘opportunity’ to play for exposure (and maybe a free beer). According to my bass-player husband, it’s a practice that continues to this day. “All you need is to learn three chords and you can call yourself a blues band,” he said. “And 90% of the people in the audience won’t know the difference.”

Of course, art buyers are not usually as drunk (or rowdy) as a Saturday night crowd in Buffalo. But the basic mechanism is the same. We’re often asked to give away the very thing that is our livelihood. If we don’t, some other artist—hungry for success—will step in to do so. Since the audiences for these events are not art-centered, they often can’t tell the difference between a masterpiece and something that will look good in their bathroom.

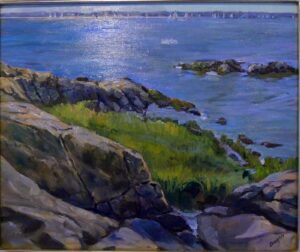

General auctions are not to be confused with events where a non-profit organization mounts an exhibition or plein air event, such as Cape Elizabeth Land Trust’s Paint for Preservation. These are generally well-run and pay both the artists and organization.

If the organization can give an artist exposure to the kind of people who will be future art buyers, it’s not a bad business plan to occasionally give away a painting. This introduces the emerging artist to the world of selling art and helps them learn to price their work. But the value to the artist is extremely limited.

You won’t be able to deduct the value of the painting on your taxes. Artists are not entitled to take deductions on charitable donations of artwork. In fact, the IRS limitations on donating art are extremely restrictive.

Non-profit organizations are perpetually fundraising, and general auctions are a favorite way of doing it. They assign a committee to gin up donations, and one or two people always seem to know artists. When it was my late friend Dean and the organization was Ducks Unlimited, I said sure. I like conservation and I loved Dean.

Believing in the mission of the organization isn’t enough. Often, your artwork is not a good match to the audience, so the work sells for a fraction of its value. A fisheries organization used to ask artists to paint wooden buoys for an annual fundraiser. I believe in their mission, so I participated. It was an interesting challenge, but also a lot of work. The buoys sold at such a discount I would have been far better off just writing them a check.

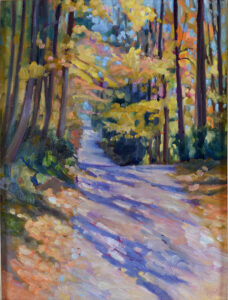

Colin Page is doing a similar fundraiser for the AIO food pantry in Rockland. It has a much greater chance of success. Artists painted wooden bowls that are available through silent auction at the Page Gallery at 23 Bay View Street in Camden from September 3-10. Colin’s a local celebrity, the cause is critical, and—most importantly—the venue is art-centered. It’s an example of how to do this right.