I watched eagerly as Cardinal electors arrive for the Papal Conclave in Rome, which starts today. Although I’m not Catholic, the Papal Conclave is a fascinating glimpse into history. The College of Cardinals have been doing this (with periodic irruptions) since 1059 AD. Only four have been held in my adult lifetime.

Much hay has been made recently about the late Pope Francis’ love of Caravaggio, in particular The Calling of St Matthew. Michelangelo, painter of the Sistine Chapel, is the artist most associated with the Vatican, but so also are Raphael, Caravaggio, Bernini, and Leonardo da Vinci.

The difference between those others and Caravaggio isn’t his chiaroscuro, as radical as it is. It’s the humanity of his figures. Although his figures are dressed in late 16th century finery, there’s an everyman quality to them that we recognize immediately.

Francis’ love of Caravaggio is ironic, considering the difficulties the artist had with his sometimes patron, Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese. Borghese was the nephew of Pope Paul V. When Paul V was elected Pope, Borghese was made a Cardinal, the papal secretary and the effective head of the Vatican government. Of course, he amassed great power and wealth. With that came the capacity to steal vast collections of art.

Included were several Caravaggios. Among them, Borghese appropriated Caravaggio’s Madonna and Child with St. Anne, commissioned in 1605 for a chapel in the Basilica of Saint Peter’s. It was rejected by the College of Cardinals, allegedly because of its earthly realism and unconventional iconography. However, archives show that Borghese rigged the deal from the start so that the altarpiece would end up in his own collection.

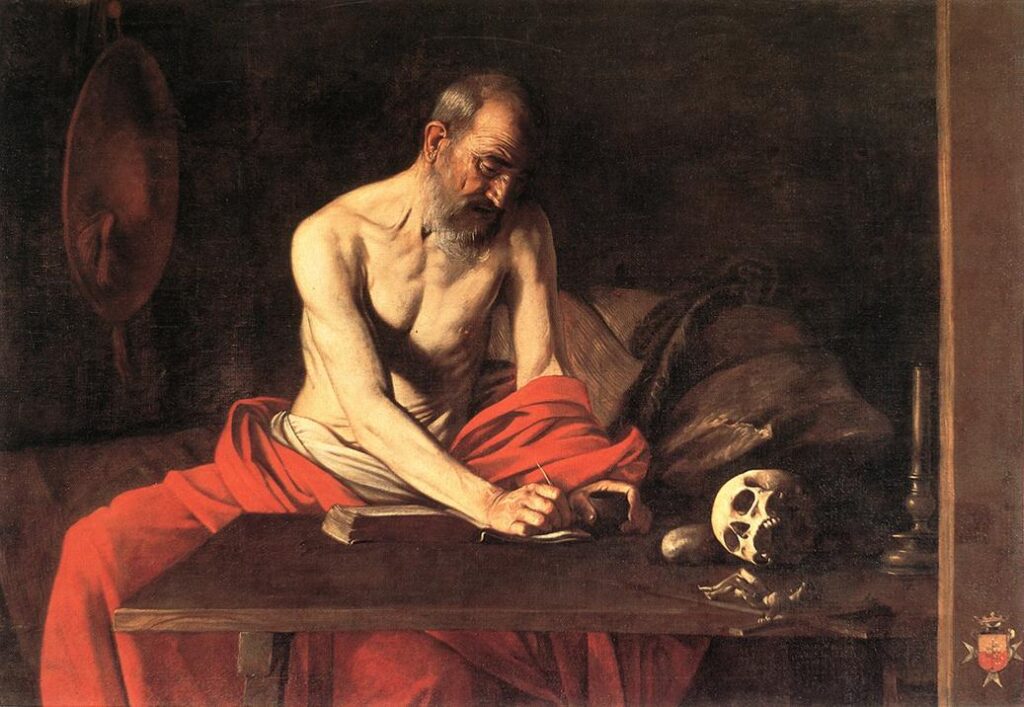

Caravaggio was temperamental to start with, but his treatment by Borghese couldn’t have helped. In 1606, he fled to Malta after murdering a gangster in a street brawl. I recently saw two of his paintings there: The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (which is enormous and dark) and Saint Jerome Writing (which is intimate and accessible). These are in St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, which was one of many exuberantly-Baroque churches, basilicas and cathedrals we toured. At the end of my visit, I felt if I spent much more time in all that gilt and paint, I’d be an atheist.

This is of course, unfair. I’m a New England evangelical, which means my church style is austere.

Having said that…

I’ve heard people say that the gold in St. Peter’s should be melted down and the money given to the poor. That’s absurd on the face of it, since every bit of gilt there is in the form of artistic masterpiece, worth many times the nominal value of the metal.

The truth is that without the church, there would be no western art. All artistic expression from the Middle Ages until the Enlightenment hangs from the power and energy of the church. The church created modern western art as we know it, including that which followed the church age.

The Reformation unleashed a wave of iconoclasm across Northern Europe and England in the 16th century. The result was the destruction of more paintings than were ever saved. The church not only commissioned great art, it has preserved it. That was sometimes in the face of danger, as in the case of the Ghent Altarpiece.

Let the games begin

Meanwhile, the Papal Conclave begins its stately procession to elect the 267th recognized pope. Let the intrigue, speculation, false starts, and rumor begin!

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

As I have stated earleir, I was most interested in seeing this painting by Caravaggio…so when we arrived in Rome, we stayed at a hotel very close to the little church it was supposed to be in…however there was construction going on in the church and it was unfortunately not available to view! 🙁

I found this history of the painting to share though…

This painting by Caravaggio of the The Conversion of Paul from Persecutor to Apostle is a well-known Biblical story. According to the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus was a zealous Pharisee, who intensely persecuted the followers of Jesus, even participating in the stoning of Stephen. He was on his way from Jerusalem to Damascus to arrest the Christians of the city.

As he went he drew near Damascus, and suddenly a light from heaven shone around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute Me?” He said, “Who are You, Lord?” The Lord said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.”[10]

Saul is almost embracing his vision

The painting depicts this moment recounted in the Acts of the Apostles, except Caravaggio has Saul falling off a horse (which is not mentioned in the story) on the road to Damascus, seeing a blinding light and hearing the voice of Jesus. For Saul this is a moment of intense religious ecstasy: he is lying on the ground, supine, eyes shut, with his legs spread and his arms raised upward as if embracing his vision. The saint is a muscular young man, and his garment looks like a Renaissance version of a Roman soldier’s attire: orange and green muscle cuirass, pteruges, tunic and boots. His plumed helmet fell off his head and his sword is lying by his side. The red cape almost looks like a blanket under his body. The horse is passing over him led by an old groom, who points his finger at the ground. He had calmed down the animal, and now prevents it treading upon Saul. The huge steed has a mottled brown and cream coat; it is still foaming at the mouth, and its hoof is hanging in the air.

The scene is lit by a strong light but the three figures are engulfed by an almost impenetrable darkness. A few faint rays on the right evoke Jesus’ epiphany but these are not the real source of the lighting, and the groom remains seemingly oblivious to the presence of the divine. Because the skewbald horse is unsaddled, it is suggested that the scene takes place in a stable instead of an open landscape.[11]

This painting has helped form the myth of Paul being on a horse although the text does not mention a horse at all. Rather in Acts 9:8 it says that afterwards “Saul got up from the ground and opened his eyes, but could not see a thing. So they took him by the hand and led him into Damascus.”

As I have stated earlier, I was most interested in seeing this painting by Caravaggio…so when we arrived in Rome, we stayed at a hotel very close to the little church it was supposed to be in…however there was construction going on in the church and it was unfortunately not available to view! 🙁

I found this history of the painting to share though…

This painting by Caravaggio of the The Conversion of Paul from Persecutor to Apostle is a well-known Biblical story. According to the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus was a zealous Pharisee, who intensely persecuted the followers of Jesus, even participating in the stoning of Stephen. He was on his way from Jerusalem to Damascus to arrest the Christians of the city.

As he went he drew near Damascus, and suddenly a light from heaven shone around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute Me?” He said, “Who are You, Lord?” The Lord said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.”[10]

Saul is almost embracing his vision

The painting depicts this moment recounted in the Acts of the Apostles, except Caravaggio has Saul falling off a horse (which is not mentioned in the story) on the road to Damascus, seeing a blinding light and hearing the voice of Jesus. For Saul this is a moment of intense religious ecstasy: he is lying on the ground, supine, eyes shut, with his legs spread and his arms raised upward as if embracing his vision. The saint is a muscular young man, and his garment looks like a Renaissance version of a Roman soldier’s attire: orange and green muscle cuirass, pteruges, tunic and boots. His plumed helmet fell off his head and his sword is lying by his side. The red cape almost looks like a blanket under his body. The horse is passing over him led by an old groom, who points his finger at the ground. He had calmed down the animal, and now prevents it treading upon Saul. The huge steed has a mottled brown and cream coat; it is still foaming at the mouth, and its hoof is hanging in the air.

The scene is lit by a strong light but the three figures are engulfed by an almost impenetrable darkness. A few faint rays on the right evoke Jesus’ epiphany but these are not the real source of the lighting, and the groom remains seemingly oblivious to the presence of the divine. Because the skewbald horse is unsaddled, it is suggested that the scene takes place in a stable instead of an open landscape.[11]

This painting has helped form the myth of Paul being on a horse although the text does not mention a horse at all. Rather in Acts 9:8 it says that afterwards “Saul got up from the ground and opened his eyes, but could not see a thing. So they took him by the hand and led him into Damascus.”