Mastering fat-over-lean will remove the need for varnishing and ensure a long life for your paintings.

|

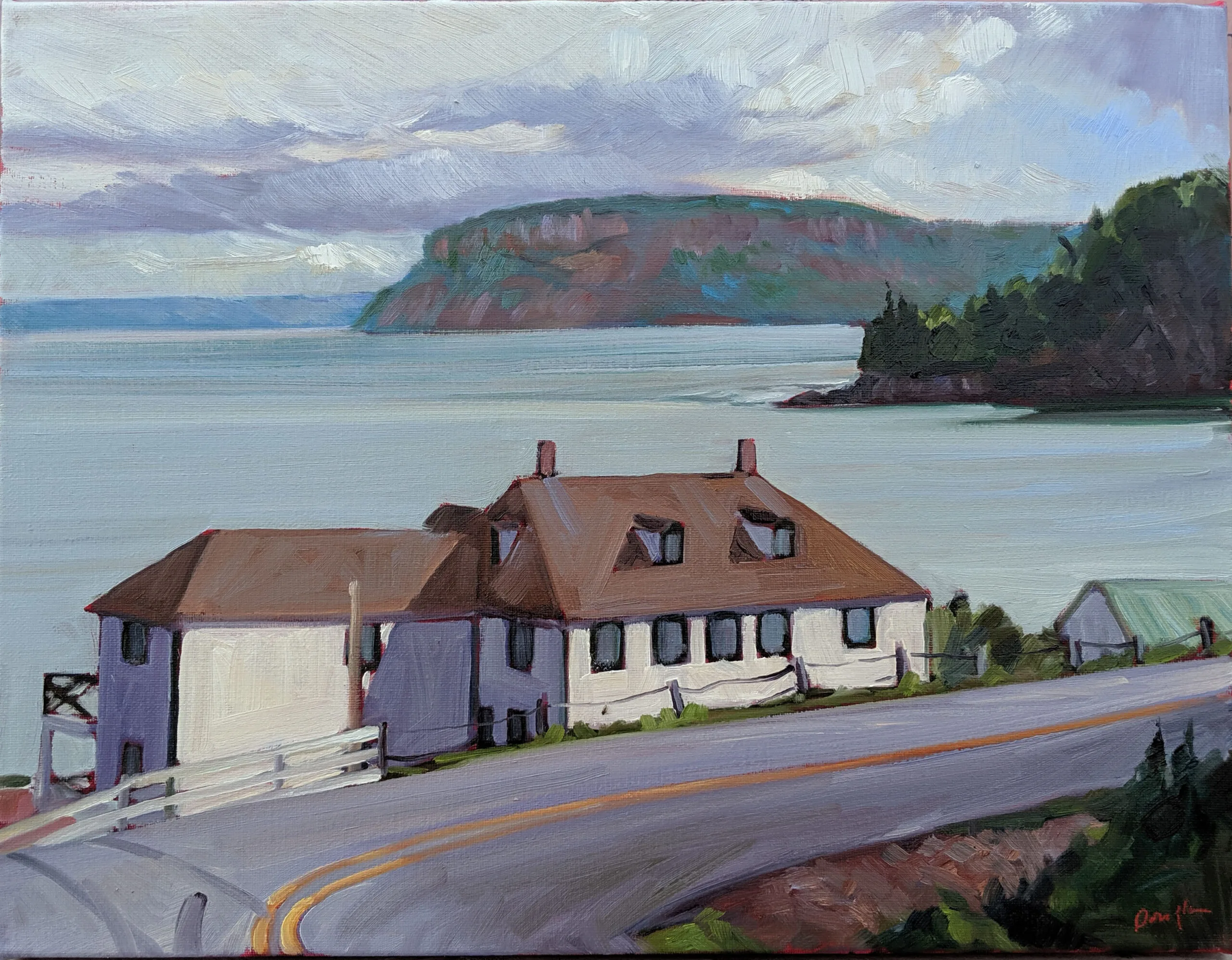

| Ottawa House, oil on canvas, available, is going in my gallery this summer. |

There are three fundamental truths of oil painting, which are:

- Big shapes to small shapes

- Darks to lights

- Fat over lean

The first one is more about how to think than about the technical aspects of oil paint. The second is a response to white paint’s infinite ability to dilute darker shades. The third is really the most difficult one to master, and the one that has long-term archival implications.

|

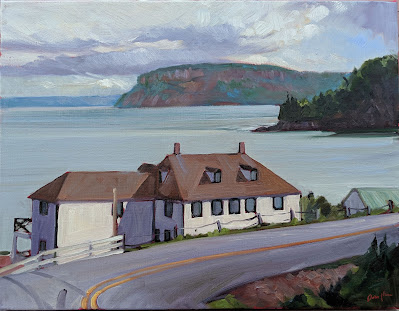

| Belfast Harbor, oil on canvas, available, is also going in my gallery this summer. |

The business of laying down paint is a craft, one that’s been developed over millennia. It’s possible to take this craft to new places, but only on a firm foundation of technique. That doesn’t mean that things don’t change; if they didn’t, we’d all be still painting encaustic funerary portraits a la the Romans. But there is still broad consensus on how oil paint is applied.

Fat-over-lean developed to prevent two problems: sinking color and cracking paint emulsion. The first is that dullish grey film that develops over paint that’s overthinned with solvent. Cracking paint doesn’t usually appear until after the artist is dead but is a major issue in some masterpieces.

Some manufacturers of alkyd mediums argue that the fat-over-lean rule no longer applies. I take this with a grain of salt. It’s a familiar argument to conservators now trying to fix 20th century masterpieces that were painted with zinc oxide, once considered a great substitute for lead white. It takes time for problems to appear in paintings, time that’s measured in decades, not years.

|

| Owl's Head, 11X14, oil on canvas, available. |

Fat over lean sounds simple, but the application is tricky. By ‘fat’ we mean the medium—either commercially-mixed mediums or drying oils like linseed, poppy or walnut. Remember that the paint itself contains some of this medium as a binder, usually in the form of linseed oil. By ‘lean’ we mean the pigment and a solvent, usually odorless mineral spirits (OMS), or, if there are unreconstructed traditionalists out there, turpentine.

The usual way to achieve this is by cutting the initial underpainting layer with OMS. Since it evaporates, it leaves a thin layer of paint on the surface. As you develop additional layers, increase the amount of paint and, ultimately, medium.

Drying oils don’t evaporate, they oxidize. That means they stay there, bonded with oxygen, creating a new chemical structure on the surface of the paint. This can be extremely durable, when done on a proper lean base.

In plein air, this process is usually cut back to two or three steps: an underpainting cut with OMS, a layer that’s pure paint, and then possibly a detail layer cut with medium on the top. However, in more complex paintings with more layers, the shift from lean to fat can be more gradual.

|

| Vineyard, 30X40, oil on canvas, available. In larger works, the shift from lean to fat is more gradual. |

Either way, you want the bottom layers to have more OMS and less oil and the top layers to have more oil and, hopefully, no OMS at all.

Another way to get there—less accepted—is to use only painting medium, starting with almost none in the bottom layers and building more and more oil into the layers as you develop the painting. However, the vast majority of painters start with thin underpainting as a means of sorting out their ideas. For them, there’s little advantage to this method.

Many painters never use medium at all. I use very little myself. I like Grumbacher’s traditional oil painting mediums (labeled I, II, and III), but the looser my method has become, the less I use at all. It’s almost always just refined linseed oil, since I can fly with it.