On Wednesday, I wrote, “Not creating is a safe position from which to operate. Your talent is inviolable, protected, a seed not open to criticism… That gives you the latitude to criticize other creators, as you are protected from criticism yourself.”

That relationship between nonachievement and criticism is famous in art schools, where bitchiness itself is often raised to a fine art. This video was a one-hit wonder but it captures the experience.

The best painters I know are also the most generous critics. They’re courteous and supportive of even the most tentative of efforts. They understand how murky and undeveloped radical new ideas can be, and they’re as curious as anyone as to how they will turn out.

“Put down the red pen,” is an editing maxim (from when writers used pens). It means that the editor should read through a piece first, with an open mind, before starting to make corrections. By coming at a piece flourishing your metaphorical red pen, you’re inclined to start rewriting the piece as you would have written it. That leaves no room for the writer’s own voice or goals.

The same is true with painting. We need to first step back and look and think. When we intervene too forcefully at the beginning, we supersede the artist’s ideas, style and voice. We take on the responsibility for refinement without asking whether that’s helpful or not. ‘I know better than you’ becomes our primary message. That might feel good (temporarily) to the critic, but it can be paralyzing to the painter.

Hostile input shuts us down

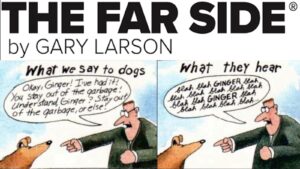

There’s plenty of science to tell us that the brain just shuts off at the first hint of stress. Comments that are perceived as personal attacks can set off a cascade of chemical events that weaken our impulse control or paralyze us with anxiety. We’ve all seen the Gary Larson cartoon (above) about what dogs hear when we yell at them. The same is particularly true of teenagers, and to a lesser degree, everyone else.

At my age, I don’t need to be diplomatic, but I do need to be kind. That’s not a moral imperative; I just want my students to hear me. One important way forward is to divorce feelings from criticism. I dislike comments that start with, “I feel…” What you feel about the artist’s use of line, color, shape and form is immaterial. What matters is what you think about those things.

Objectivity is our goal

Here is a framework for objective criticism. These aren’t my ideas; they’re standard criteria for design. Obviously, there’s room in critique for the subjective, since art is ultimately a personal expression. However, these questions can also be framed in non-inflammatory ways. “Does this evoke a response in you,” is a very different question from, “is this painting boring?”

It’s far healthier to learn to apply these standards of criticism to your own paintings than to cast around for approval from your peers (although we’ve all done it). Learning to critique your own work as you go will save you a lot of flailing around.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.