When I’m teaching workshops and classes, I frequently ask students, “What’s your takeaway lesson here?” Last week my workshop students got a deep dive into two artists’ working method: Andrew Wyeth‘s, through a guided tour of the Farnsworth Art Museum, and Colin Page‘s, from the maestro himself.

“Painting is easy,” Colin said. “It’s the preparation that’s hard.” I smiled, because that’s something I frequently say as well. Wyeth didn’t whisper it from beyond the grave, but his methodology is spelled out in the museum. For his studio paintings, he was a consummate draftsman who made many sketches and paid meticulous attention to detail.

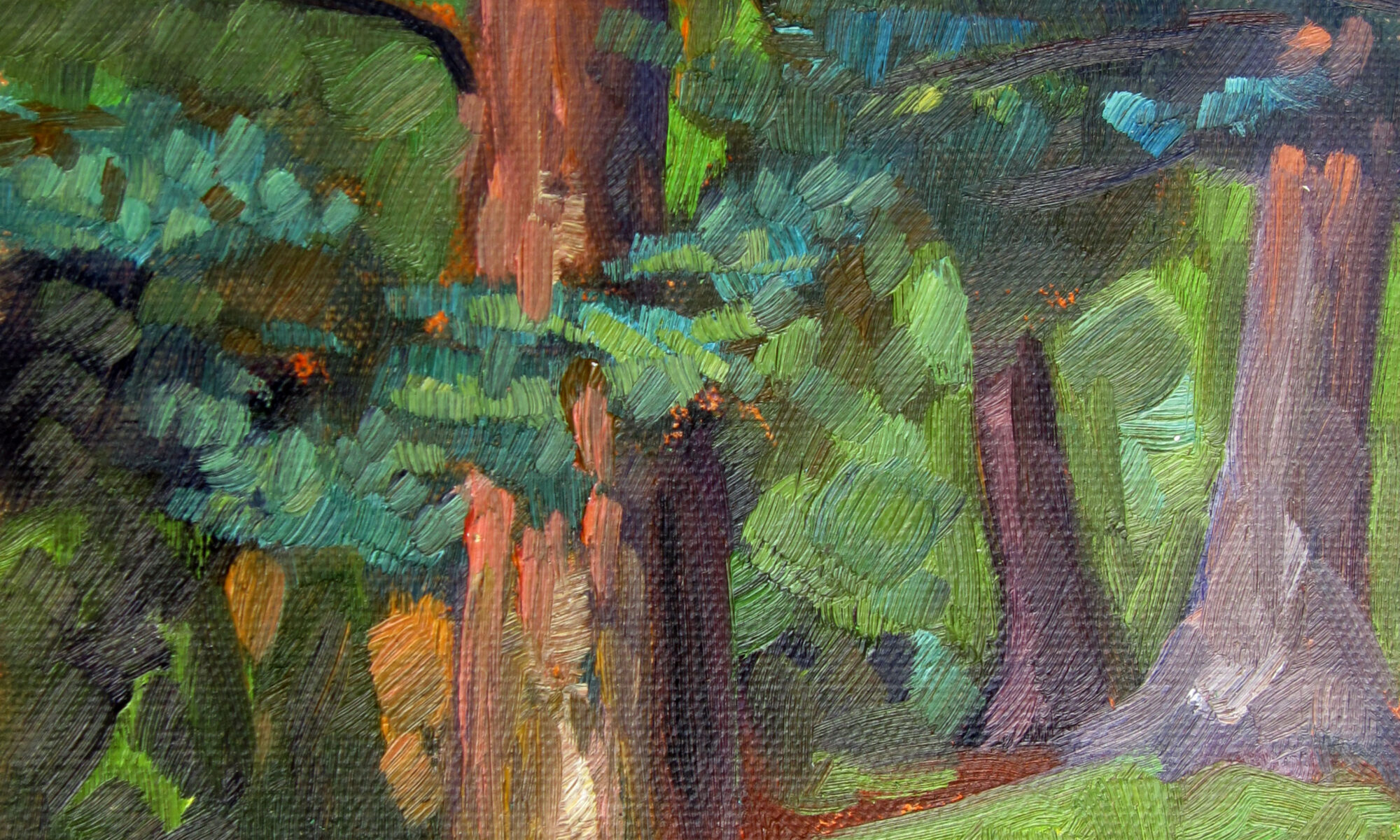

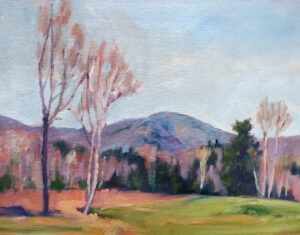

Students frequently ask me how to achieve loose brushwork. My first question is why they want that, as it’s not a universal value. Rather it’s a question of style. Linear painting is based on line and boundary; the artist sees in clear shapes and outline. Painterly painting focuses on the interactions of masses, shadows, and merged shapes. An example of a contemporary linear landscape painter is Linden Frederick. An example of a contemporary painterly landscape painter is Kevin Macpherson. Neither style is ‘better,’ they’re just different. And there are many painters (including me) who work in the middle somewhere.

When Arthur Rubinstein was asked if he believed people when they told him he was the greatest pianist of the 20th century, he replied, “Not only I don’t believe them, I get very angry when I hear that, because it is absolute, sheer, horrible nonsense. There isn’t such a thing as the greatest pianist of any time. Nothing in art can be the best. It is only… different.”

What is a universal value in art is assurance, and that rests on the back of solid preparation. Rubinstein joked that he was lazy and didn’t like to practice, but he still spent 6-9 hours a day at the piano. “And a strange thing happened. I began to discover new meanings, new qualities, new possibilities in music that I have been regularly playing for more than 30 years.”

The same thing is true of painting, as is its obverse-the less preparation you do, the more you’ll fumble in performance. And the more you must redraw, reposition, reset values, or restate, the less immediate and assured your brushwork will be. That’s as true in oils, acrylics and pastels as it is in watercolor.

What does that mean for the emerging artist? At a minimum, you should do a carefully-realized sketch, considered in terms of compositional patterns of darks and lights. This sketch should be moved to the canvas or paper accurately; if that requires gridding, then you should grid. Colors should be tested first for value, and then to how they relate to the overall key of the painting.

Yes, I know artists who don’t do these things. They can be sorted into two groups. The first are those who are very experienced. They’ve learned what corners they can cut (which are not the same for everyone). The second are impatient beginning and intermediate painters. They almost always fail in the preparation, and then they wonder why they’re flailing around in the painting stage.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.