A grisaille is a monochromatic painting. In oil painting, it forms the first step of underpainting. In watercolor, it’s a separate reference to check values.

There are a few painters I know who skip the grisaille step entirely. (I’m not one of them.) The only ones who are successful at it are so experienced that they can integrate hue, value and chroma simultaneously. Even then, they’re still working dark to light and being careful not to misstep and put gobs of white or light paint where it doesn’t belong.

Eric Jacobsen is one of these outliers, and he graciously offered to demo his underpainting technique for my newest online class, The Essential Grisaille. (Appearances by his dog Sugar and his chickens were completely unscripted – but cute.)

As we filmed, I kept thinking, “Kids, don’t try this at home!” Eric isn’t skipping the grisaille step so much as integrating it with his initial color notes. That’s very difficult for all but the most experienced painters.

Why grisaille?

The human mind sees value before hue or chroma. The arrangement of rods and cones makes us more sensitive to value shifts when scanning a vista. We also have a wide dynamic range. Both were awfully convenient for our hunter-gatherer ancestors, and they influence how we see paintings.

In the brain, processing starts with low-level information like brightness and contrast. That’s processed more quickly and efficiently than higher-level color information, which requires additional signals from the eyes.

In a nutshell, that means the viewer will see your value structure before he or she sees anything else. A painting that fails on its value structure will just fail, period. Arthur Wesley Dow, who wrote the definitive 20th century composition book, is the guy who gave us the notion of notan. He taught students to restrict the infinite range of tonal values to specific values. He wanted students to realize that all compositions are, underneath, a structure of light and dark shapes. That’s a critical insight that influences all modern painting.

What is grisaille?

Grisaille just means a monochromatic painting. I teach both oil and watercolor students to do this preparatory step. In watercolor, it’s a monochrome study on a separate page that guides the color choices for the finished painting. For oil painting it’s the underpainting step before we start adding color.

In oils, it’s done in a dark tone that relates to the overall color scheme of the planned painting-if the shadows are cool, the grisaille should be cool, and if the shadows are warm, the grisaille should be warm. That’s because the grisaille will be part of the finished painting, sometimes visible with no covering whatsoever.

The paint is thinned with odorless mineral spirits (OMS) and no white or light colors should be introduced. A brush and a rag are both used to get the full range of values.

Simple, right?

I’ve just spent about six weeks writing and filming The Essential Grisaille*, and thinking through all the ways it can go wrong. Julie Hunt, who is a very good student and painter, told me, “There were beginning things I fudged with little instruction that I remember.” She has now carefully worked through every step of The Essential Grisaille to really master the subject. I’m excited to see how her painting changes.

Julie has put her finger on the difficulty of all classes, online or in person. There’s so much to take in that nobody gets it all the first time they hear it. And we can fill in the gaps with inspired guesses or just wrong-headed mistakes. It all comes down to being ready to hear, grasshopper.

Which is why Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painters is designed to be open-ended. You can go back and revisit them… as long as I pay my internet bill.😊

*I’m talking about both watercolor and oils in this post, but The Essential Grisaille is intended for oil painters.

My 2024 workshops:

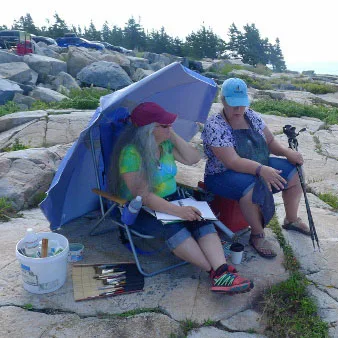

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.