The ‘golden hour’ is that period after dawn and before sunset when the light is warm and the shadows are long and blue. The farther north you go, the longer the golden hour lasts. in midsummer in Maine, we have very little of that ‘dead light’ that so bedevils painters in more southerly climes.

Sunlight is composed of a spectrum of colors, which we observe when it passes through a prism, as when raindrops create a rainbow. This dispersion reveals the visible (to humans) spectrum of light. Combined equally, these colors make white light. But sunlight is seldom pure white. It is generally some tint of color – often a warm yellow, depending on the time of day and the weather.

There are instances when natural light can appear quite cool; for example, on an overcast day or at sea, when the reflected blue water and sky can tint everything blue. At midday in midsummer, when the sun is at the highest point in the sky, the light can be so blindingly white that it looks cool.

When light shines on an object, that object absorbs certain wavelengths of light and reflects others. The warmer the ambient light, the warmer the light bouncing back at us from that object.

What color are shadows?

Shadows do not have an inherent color of their own. When an object casts a shadow, it blocks some of the light from reaching the area behind it. The shadow will be a different hue than the lighted part, because the shadow is not illuminated directly by the light source. Its hue is influenced by the absence of the reflected light and by the colors of the surrounding environment.

As a matter of mental shorthand, we say that the shadows are the complement of the light source, but this is not exactly true. We think the complement of yellow light should be violet, but that’s in subtractive color (the same system of color that gives us paints and inks). The primary subtractive colors are red, blue, and yellow, and their complements are green, orange, and violet.

However, light creates additive color, with different primaries and complements. The primary colors are red, green and blue, and their complements are cyan, magenta, and yellow.

That means the complement of our yellow light is blue, and the complement of peachy light would be more on the greenish-blue side. However, there’s another aspect of light at play. Just as distant objects can appear blue-violet because of the scattering of blue light, shadows can sometimes look blue-violet due to the scattering of shorter wavelengths of light.

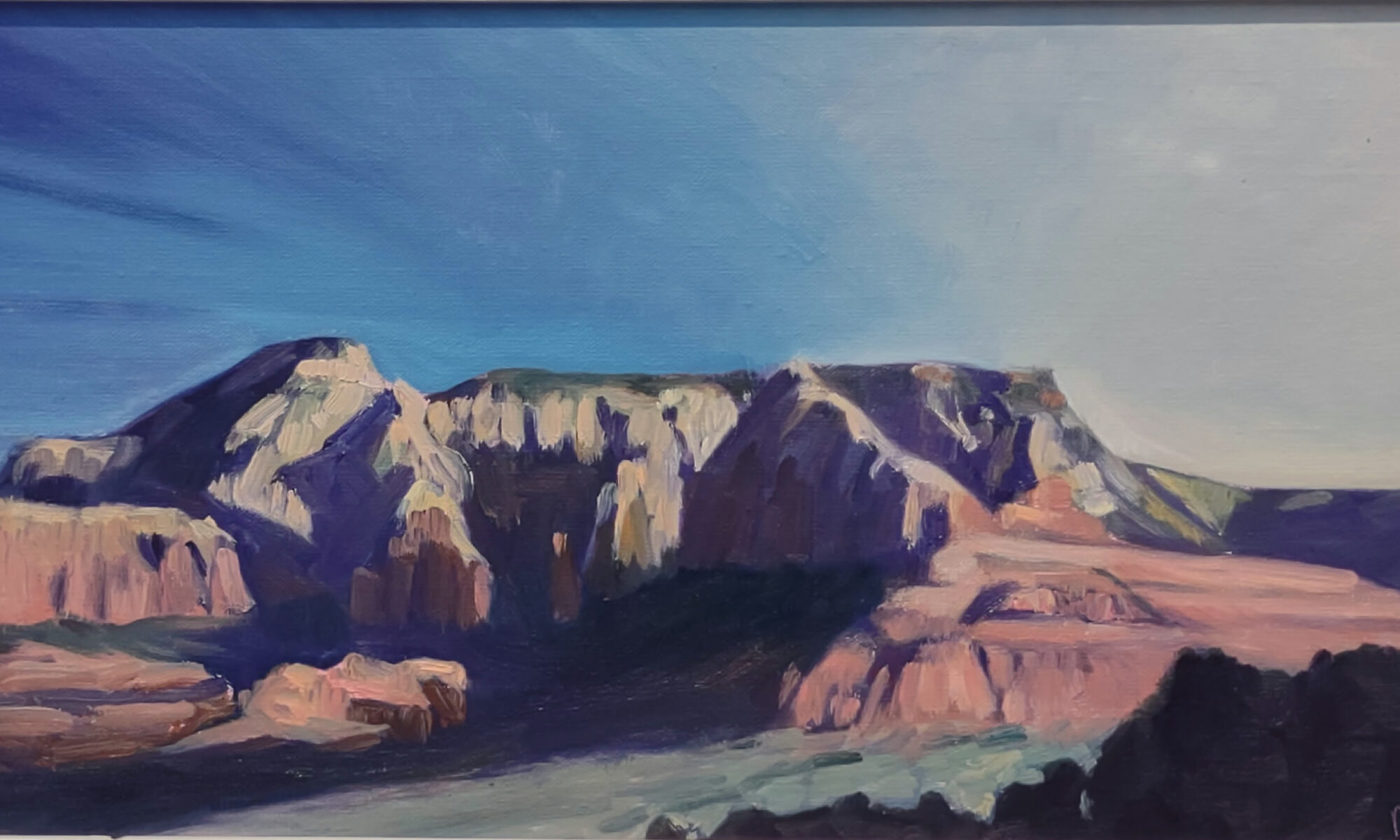

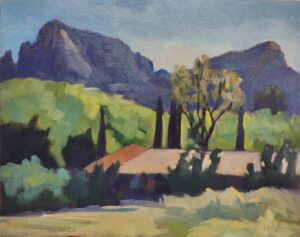

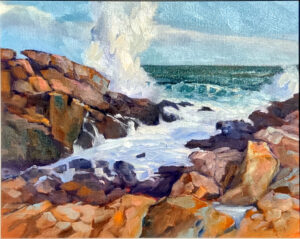

Your eye-brain connection sees things interpretively. You may see the same blue shadows in the three photographs at top, but I’ve sampled them and they’re not the same at all. In fact, they’re not even blue, but rather three variations of a soft blueish-grey. Your mind perceives the lack of warmth in the shadows as coolness. In this case it’s better to trust your mind than the hard ‘facts’ of camera and laptop.

You’ll outsmart your audience if you just remember that if the light is warm, the shadows will be cool, and vice-versa. Landscape painting tends to have warm light and cool shadows, while figure and portrait painting tend to use cool light and warm shadows. (There are of course many examples disproving this general rule.)

The exception to this is filtered light. Its shadows and lighter passages will be variations of the same color temperature. This is how we instinctively know that something we’re seeing is under an awning, for example.

Study the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla to understand the color of light. He was the master of warm and cool passages.

My 2024 workshops:

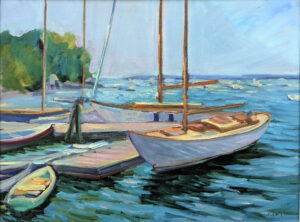

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.