T. is the only artist I’ve known who’s ever retired. Most of them paint their way forward into extreme old age. And T. couldn’t stay retired-in the last year she’s picked up her brushes again, done a solo show, and sold a few pieces.

“Why would I stop doing what I love?” asked pastellist Diane Leifheit in response to Transcending Popular Culture.

Old age often produces great work

By modern standards, Rembrandt didn’t live long, but 63 beat his contemporary odds by a long shot. His last self-portrait, painted the year of his death, is both technically confident and psychologically insightful.

Norman Mailer finished his last novel, The Castle in the Forest, right before his death at the age of 84. It was both very long and very good, and was the first volume of an intended trilogy.

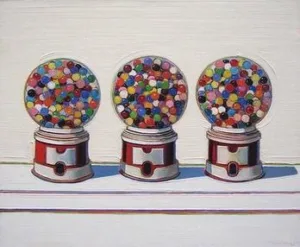

The superstar of working into extreme old age was American pop artist Wayne Thiebaud, who died on Christmas Day 2021 at the age of 101. Earlier that year, he recorded a conversation with curator Karen Wilkin and Lois Dodd, about working into old age.

“It has never ceased to thrill and amaze me,” Thiebaud said, “the magic of what happens when you put one bit of paint next to another. “I wake up every morning and paint. I’ll be damned but I just can’t stop.”

Lois Dodd, of course, we claim as Maine’s own favorite daughter. She’ll celebrate her 96th birthday this year, as will her fellow modernist Alex Katz.

Carmen Herrera didn’t have her first solo show until she was in her mid-50s, although she’d sold her first work while in her teens. She was almost 90 when she was ‘discovered’ by the New York art scene. She lived until age 106.

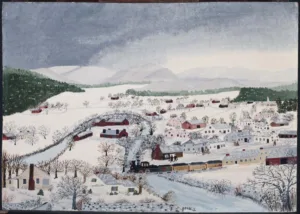

A list of major artists who’ve reached their centenary is too long to reprint here, but mention must be made of Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses. She was a hardscrabble farmer’s wife who didn’t start painting until her mid-70s. She died at age 101, having carved out a second career that was far more successful than her first one.

“I look back on my life like a good day’s work, it was done and I feel satisfied with it. I was happy and contented, I knew nothing better and made the best out of what life offered,” she said.

Science says

The anecdotal evidence I’ve related above is supported by science. British researchers found that people over 50 who regularly engaged in the arts were 31% less likely to die during a 14-year follow-up than peers with no art in their lives. A World Health Organization review found that both passive engagement with the arts (like visiting a museum) and active participation (making art or music) had health benefits.

Why don’t more people engage in art, then? We start devaluing it in school, where it’s the first thing cut, despite manifest evidence of its health and intellectual benefits. It’s no wonder that by middle age, most of us are more likely to be watching TV than picking up a brush or singing in a choir.

But as Grandma Moses demonstrated, it’s never too late to start painting. Or singing, playing the harmonium, or taking up interpretive dance. Why not give yourself a health boost, and have fun at the same time?

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.