“Art is eternal,” read yet another meme on Facebook. Not surprisingly, artists like to repeat this. But art is no more eternal than any other handiwork of man.

History is replete with examples of art that is gone. The Colossus of Rhodes. The Great Library of Alexandria and all it contained. The Great Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Karnak. The 69 ancient Greek bronze statues of Olympic victors that once graced the sanctuary of Olympia. The menorah from the Second Temple, which was stolen when the Romans sacked Jerusalem; then it disappeared from Rome. The Imperial Seal of China.

Whole cities have been sacked, like Athens, Constantinople, or Kaifeng. Their art was destroyed with them. Insurgency and war destroy art, as in the French Revolution. Conquerors loot and lose it; Napoleon and the Nazis are just two examples.

This fall we had a massive fire in Port Clyde, ME. It destroyed several historic buildings and paintings by Jamie Wyeth and Kevin Beers. They were gone with sudden finality, and we were shocked and grieved.

There are spasms of iconoclastic fury that convulse humankind. The Beeldenstorm of the 16th century is the most well-known. The Reformation wanted to purge Northern Europe of Catholic ideology. What better way to attack it than through art? In England, 90% of religious art was destroyed. The percentages were probably similar in Germany and the Low Countries.

Occasionally, great works are saved from iconoclasm by very brave people. The Van Eycks‘ Ghent Altarpiece, is an outstanding example of Early Netherlandish painting. It was already famous in August of 1556 when the Beeldenstorm hit Ghent. The first attack on the Cathedral was repelled by guards. On the second try, the rioters used a tree trunk to batter through the doors. But by then the panels and the guards had been hidden on a narrow spiral staircase within the tower. They were eventually moved to a new hiding spot in the town hall, but the original frame, itself a work of art, was destroyed.

To put that in context, imagine trying to stop the Taliban as they blew up the Buddhas of Bamiyam.

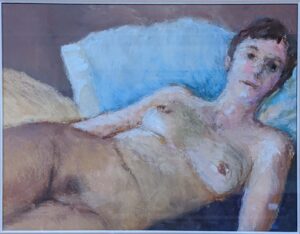

Art isn’t even above fickle fashion. It’s easy to date paintings because every era has its tropes. Right now, we’re in a long period where color is ascendent over detail. To the next generation, that will look as old-fashioned as leg o’ mutton sleeves look to us.

I told my daughter that when I die, AI should be able to reproduce me well enough to go on teaching my classes without me. “I won’t do that,” she said. “Your paintings will go up in value when you’re dead.” That is probably, true, but I’m not painting to impress people after I’m gone. Nor should you.

Our job as artists is to speak to the living. The Beeldenstorm happened because Protestants knew how powerful art is. The Nazis destroyed ‘degenerate’ art for the same reason. That’s what motivated the Taliban.

Of course, art can reach across the centuries to speak to us. Consider paleolithic cave art and its makers. We know almost nothing of their culture: we have no dishes, spears, firepits, foods, dwellings or traces of language. All we have is art: figurines, bone carvings, a few decorated tools and lots of cave paintings from all over the world. These speak to us powerfully but wordlessly. I don’t care if my own painting lasts 500 years, let alone 35,000 years, but I’m sure glad their art has.

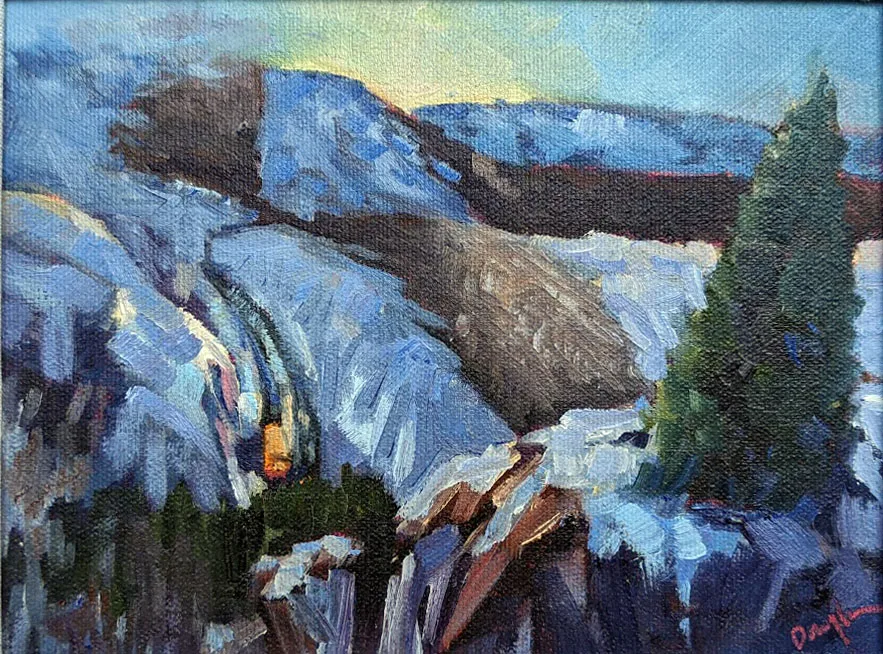

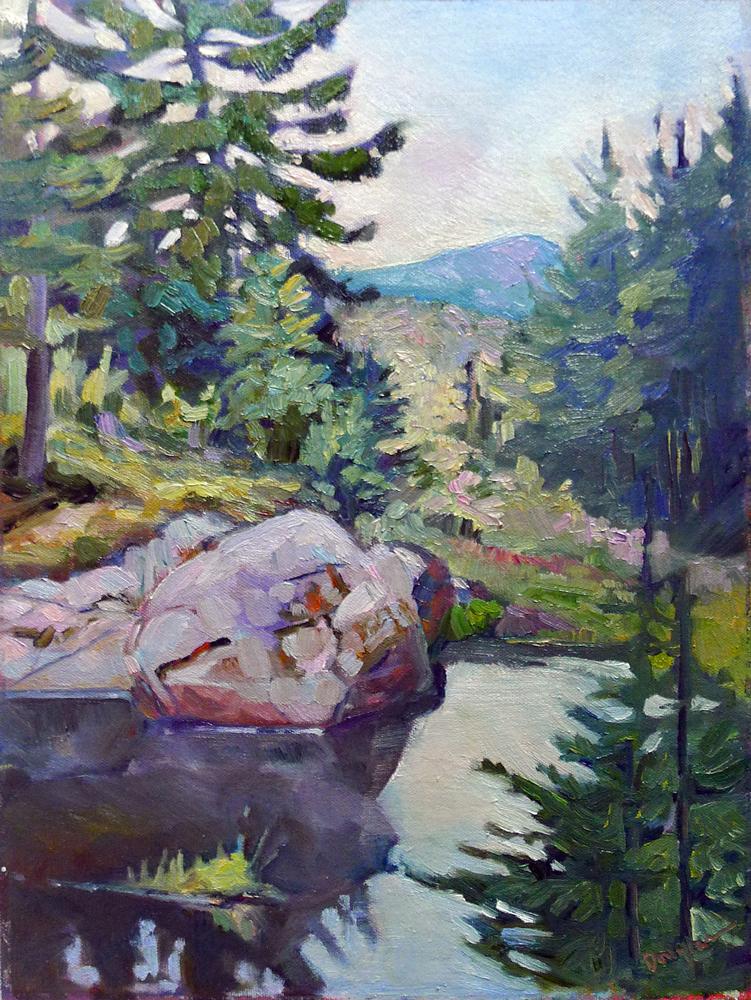

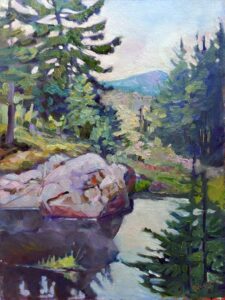

Until the first of the year, you can use the discount code THANKYOUPAINTING10 to get 10% off these or any other painting on my website. Shipping and handling are always included within the continental US, but I’m afraid I’ll no longer be able to get them to you by Christmas.

My 2024 workshops:

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.