Bob the Builder was making humorous suggestions about how a surgeon might fix my husband’s spine. A little expanding foam, some nuts and bolts strategically deployed…

“Ah, thinking outside the box, are we?” Doug laughed.

“Nope, just being silly,” Bob answered. “Unless you can build the box, define the box and work inside the box you're not thinking outside the box. You're just being random.”

Albert Einstein challenged classic Newtonian physics by arguing that time and space are relative, but he did so after earning a doctorate in physics. Elon Musk is a business disruptor, but he holds degrees in physics and business (from the Wharton School). Warren Buffett acquired an incredible $121 billion with value investing but he’s another Wharton School (and Columbia Business School) graduate. And the list goes on and on.

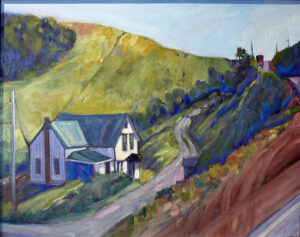

There are two kinds of behavior that aren’t thinking outside the box. The first is excessive orthodoxy. In investment, medicine and—yes—painting, that’s a strategy that inevitably leads to failure. “No change is itself change,” my friend Lois Geiss was fond of telling me.

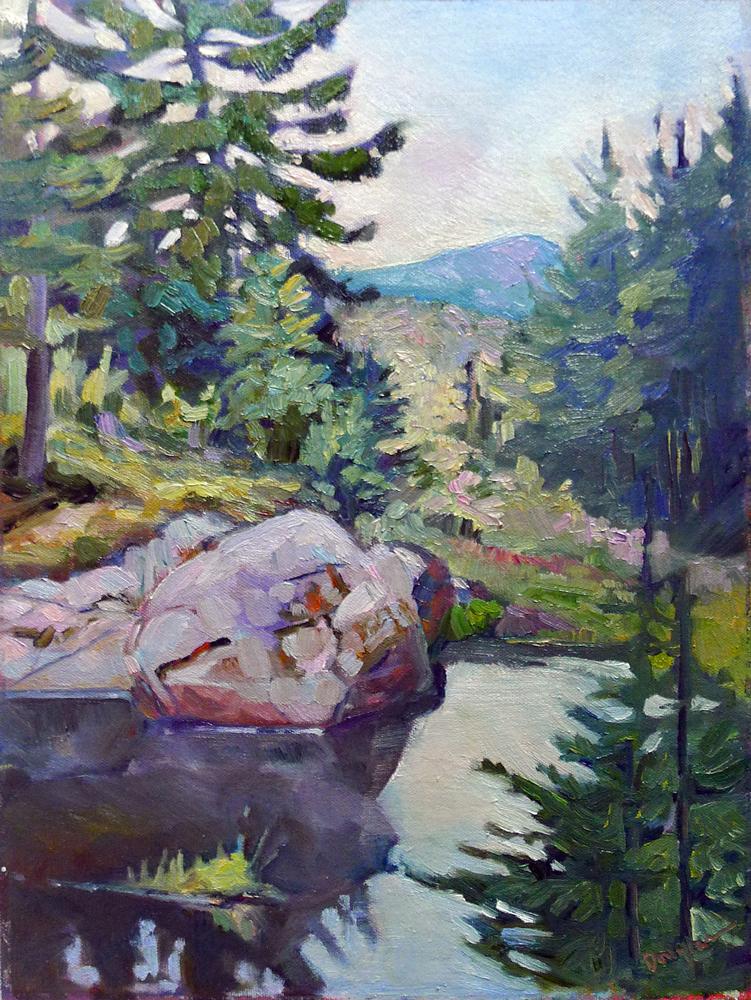

The second problem is more common among artists, and that’s confusing technique with hidebound conservatism. Those who’ve made the greatest intellectual leaps in painting, like Einstein, Musk, and Buffett, first learned the conventional way it’s done.

I’m not advocating for a college degree in art here—in fact, with prices as they are I think private art colleges are bad value for money. But I am advocating for learning traditional technique.

Creativity rests on technique

Once a friend was fretting about how she couldn’t find an uncomplicated muffin recipe. “But they’re all just lists of ingredients,” I said. “You always assemble them in the same order: sift the dry ingredients together, beat the wet ingredients together, and then fold the two mixtures into each other.”

I mentioned this to Jane Bartlett, who remarked that when she taught shibori she frequently told her students that nobody owns technique. This is a very apt observation for both baking and the fine arts. There is nothing one can patent about artistic technique, any more than one could patent the order of operations for baking.

Painting is so straightforward that departing from the accepted protocols is often foolish. For example, there’s excessive oiling-out or painting into wet glazes. The tonalist Albert Pinkham Ryder did something similar in the 19th century, and his works have almost all darkened or totally disintegrated.

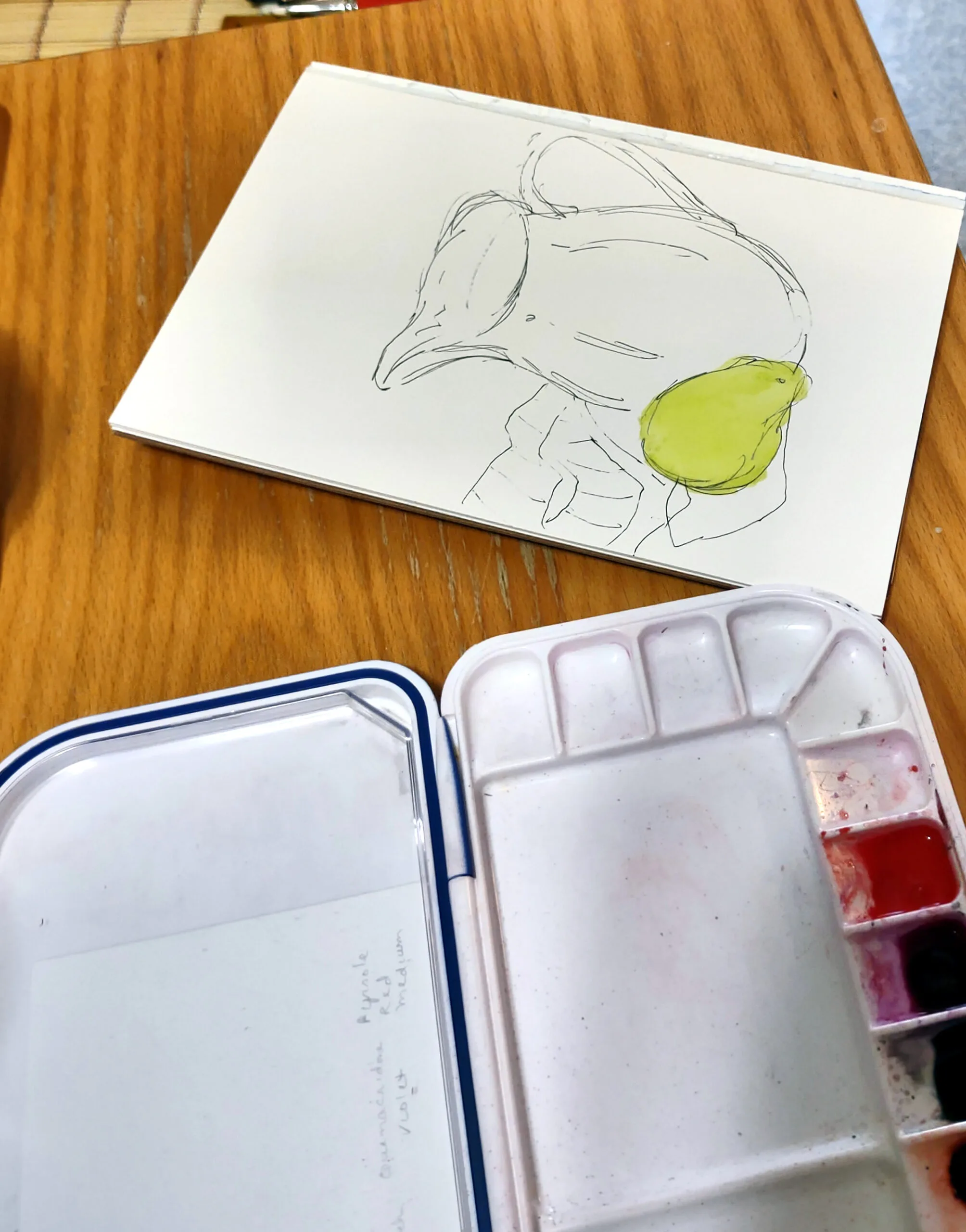

One can learn a lot from books, but one can’t learn everything. A decade ago, my goddaughter told me she was going to make an apple pie. Her parents ran a Chinese restaurant, so all of them are excellent cooks. However, pie wasn’t in their repertory. Imagine my surprise when this was what she came up with:

Ten years later, Sandy’s helped me make many apple pies. She knows what one looks like and tastes like. It helps to have assembled an apple pie under someone else’s tutelage. The same is—of course—true of painting and drawing. Yes, one can learn a great deal about technique from books, videos, and visits to art galleries, but a good teacher really does help.