Is there a right or wrong way to do art? That’s a question that artists have debated for centuries. Just to be slippery here, there’s no right or wrong answer.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres would have been baffled by Tracy Emin’s My Bed, which was shortlisted for the 1999 Turner Prize. It’s just a dirty, unmade bed, surrounded by feminine detritus. (For the record, a quarter of a century later, I’m annoyed that it sold at auction for £2,546,500 when paintings by Great Britain’s greatest late-20th century painter, James Morrison, could be had for a few thousand pounds.)

For Ingres and other Neoclassical painters, My Bed would definitely be considered the wrong way to do art. To be fair, they would also have thought that Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh were short of art technique.

Aesthetics is a moving target. But that doesn’t mean that art operates in a value-free world, although some of the art world’s excesses might have you believe otherwise.

The creative side of the argument

Art is ultimately a form of expression and communication, and each of us has a specific viewpoint and our own voice. Art history is full of rule-breakers who changed the direction of the visual arts.

In terms of personal expression, the only unbreakable rule is honesty in intention. Ironically, that’s one rule I find myself breaking all the time. It’s easy to give lip service to intellectual and emotional transparency, but just when I think I’ve gotten there, I realize I’ve thrown up another wall.

The technical side of the question.

Within specific disciplines, there are standards of craft and technique. These include the fundamental elements of design, the practical business of getting your ideas from concept to execution, and theoretical aspects like color theory. I’ve had the occasional student who believed that learning these things limited their range of expression. In fact, not knowing art technique left them flailing around. The learning curve can be steep when you’re teaching yourself by experimenting.

Different disciplines suit different purposes, audiences and intentions. You wouldn’t play Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto in D minor at your local dive, and Proud Mary wouldn’t go over too well at the Metropolitan Opera. Likewise, it would be peculiar to do encaustic in a plein air event, or completely abstract a portrait commission.

Where does that leave you?

First, learn the rules, so that when you break them, you do so intentionally and with purpose. That means understanding why people have traditionally done things in the order they’ve done them. When you do break rules, understand the consequences.

Stay open to growth. We never want to become parodies of ourselves, and that requires accepting change.

I had an epiphany this week, which was that sometimes you have to wait a long time for epiphanies. They simply can’t be rushed. The only way through the drought is to keep thinking and working. Sometimes I just hate that.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

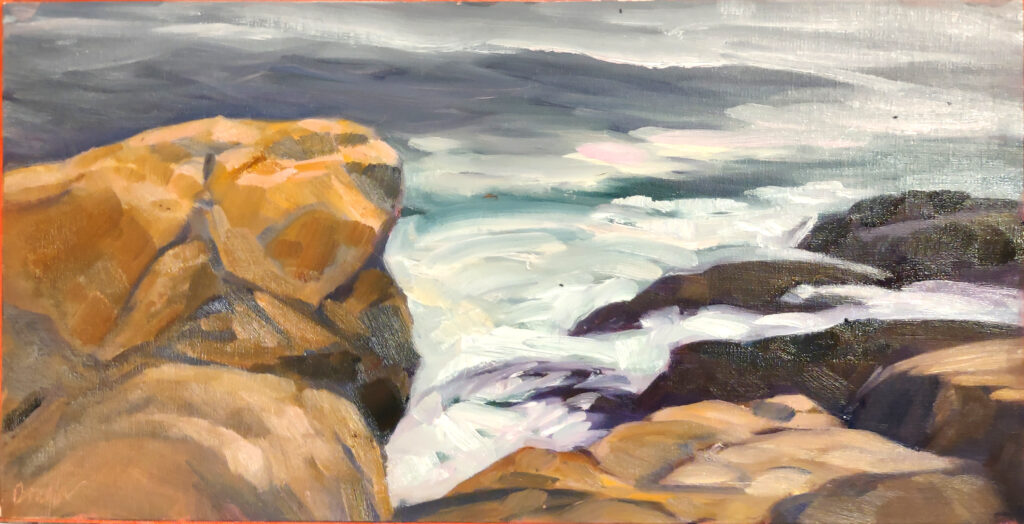

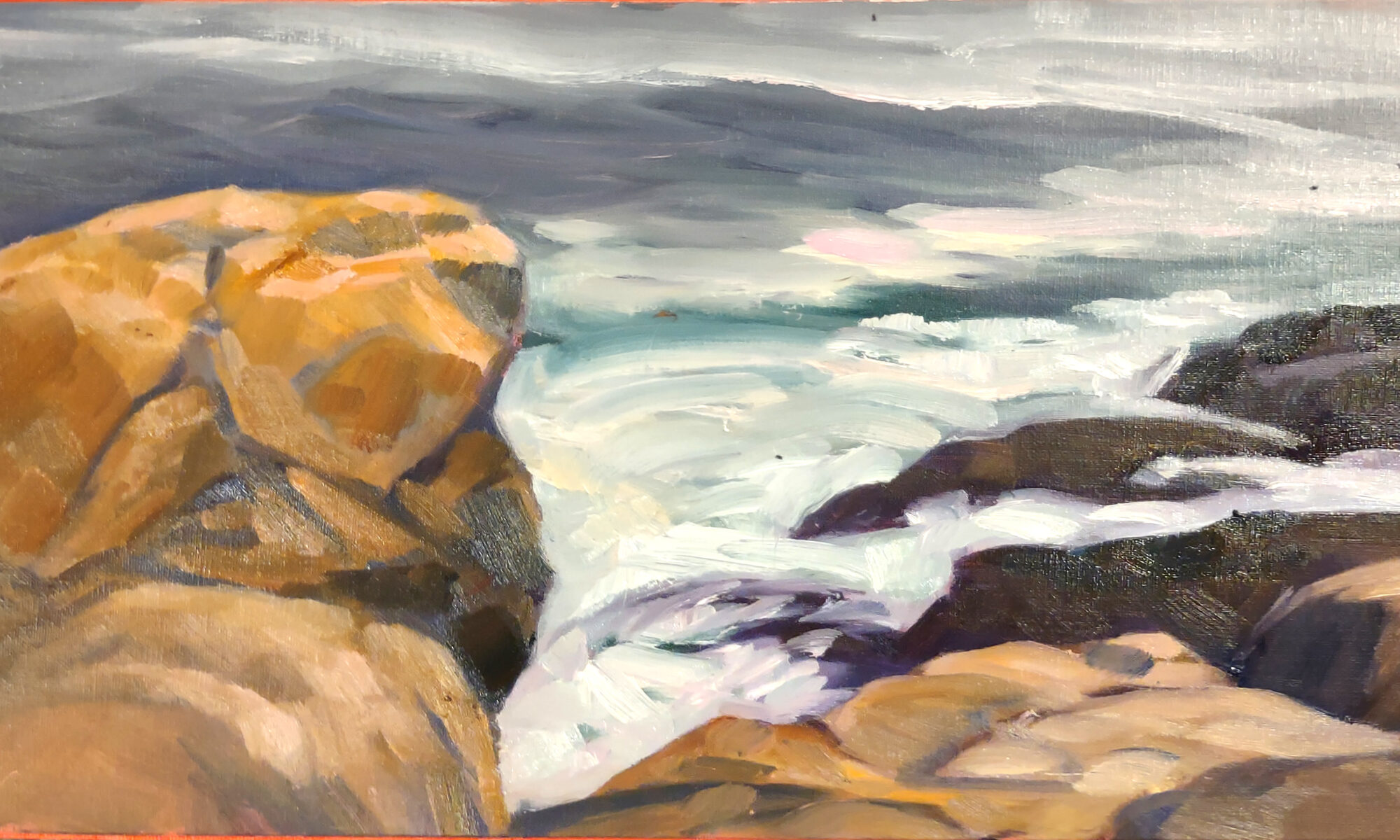

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

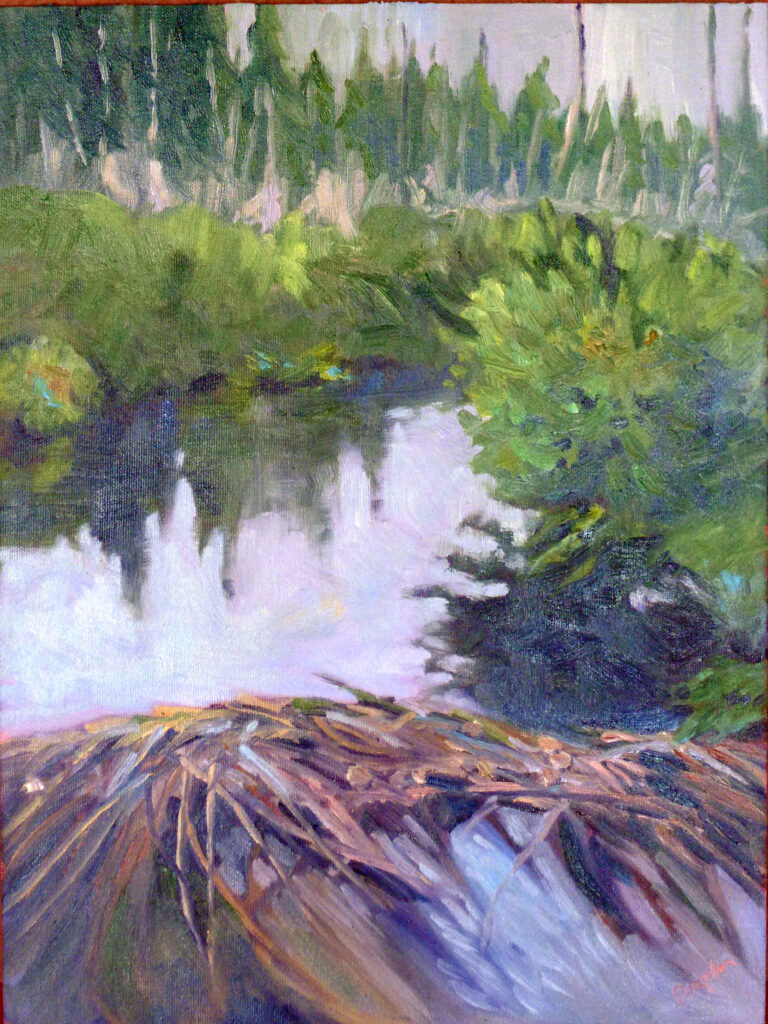

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

Love this 🙂

Add feeling to thinking and working… a trifecta

Love the Bunker Hill Overlook