Before I get into this, we’ve updated all our 2024 workshops. We’ll be sending out coupons with discount codes soon; if you’re not on my mailing list already, sign up in the box to the right.

Each week until the end of the year I’ll be giving you a behind-the-scenes look at one of my favorite paintings. These are paintings that are available for you to purchase unless otherwise noted.

Plein air painters sometimes avoid work by endless texting about possible locations. Or, we can get into our cars and drive around, but with gas hovering at $4 a gallon that hasn’t been practical. A good artist can make a painting with the thinnest tissue of material, so you know that when we do that, we’re ducking something.

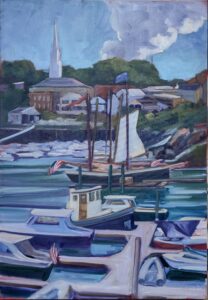

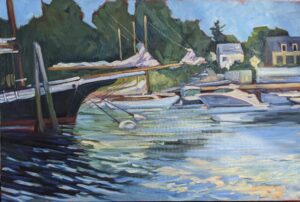

I can almost always persuade Eric Jacobsen to come out to Owl’s Head. It has great fishing shacks and a stellar working harbor. The tiny hamlet of Owls Head has resisted the tarting up that’s marred parts of midcoast Maine. Plus, the Owl’s Head General Store has reopened and my sources say it is as good as ever.

There’s a house in Owl’s Head that’s been empty for around eight years (I heard it recently changed hands again; may this time be the charm.) I don’t know its specific story, but the phenomenon of the abandoned house has always bothered me. Sometimes it’s about lack of jobs in an area, or getting behind on taxes. Equally, it can be caused by friction between heirs, divorce or other ructions, which tear away at property as much as they tear away at human beings. But a house is a middle-class person’s biggest asset, so letting one moulder seems all wrong.

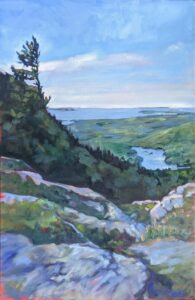

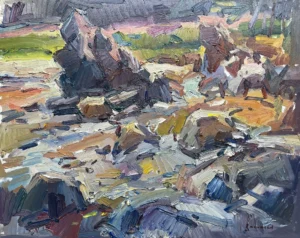

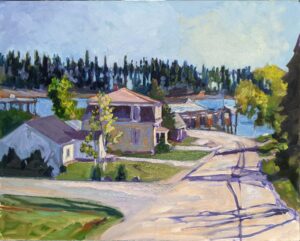

This is not a painting of that abandoned house. Rather, I painted it from that house’s front yard. I’d intended to paint the house itself once again, but as Eric and I stood scoping our vistas, I realized that I’d always wanted to paint the view downhill. That hip-roofed foursquare house is a coastal Maine gem, and its owners have carefully preserved its charm.

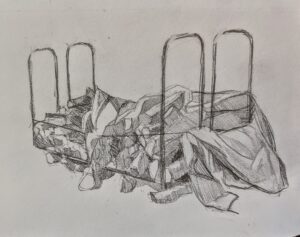

Eric set up looking uphill, and I set up looking downhill. This is where I developed my own version of Ken DeWaard’s Park-N-Paint, where I sit in a lawn chair in the bed of my truck with my feet up on a box. It’s so relaxed that Colin Page once asked me, “Carol, can’t you at least look like you’re working?”

That illusion of inertia must work, because when I was done, Eric said, “that’s great, Carol.” For once I agreed with him. It remains one of my favorite paintings.

Main Street, Owl’s Head is 16X20 and available for $1623. The whiff of seawater and sunlight is included free.

My 2024 workshops:

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.