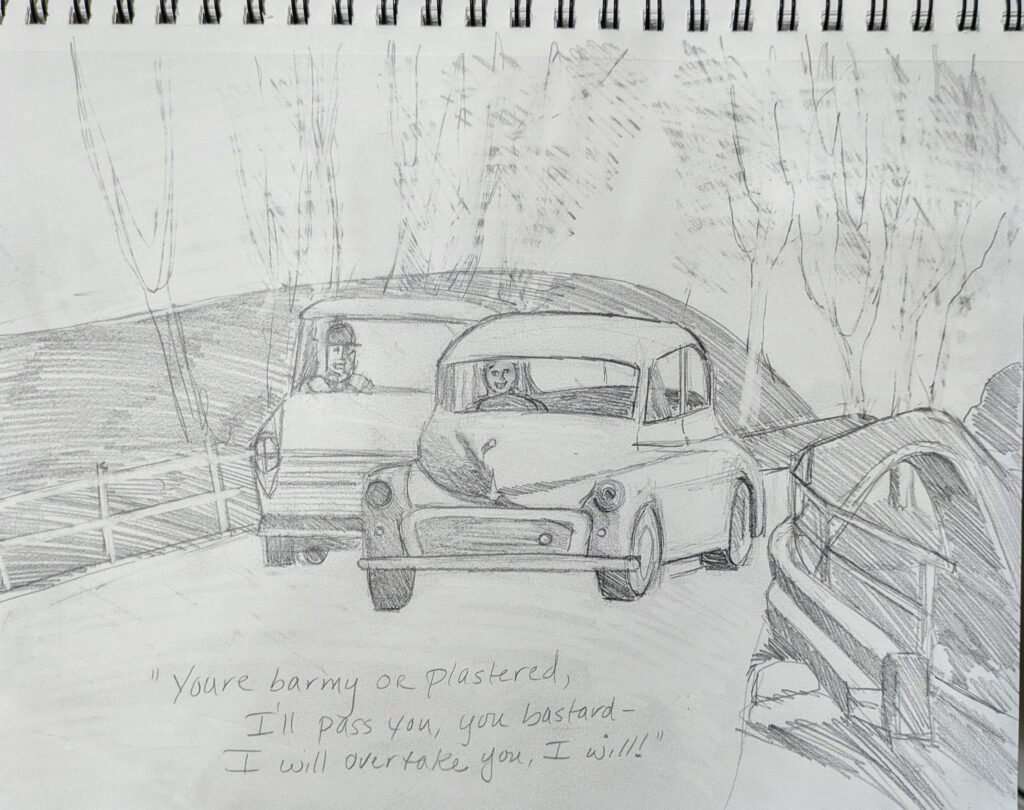

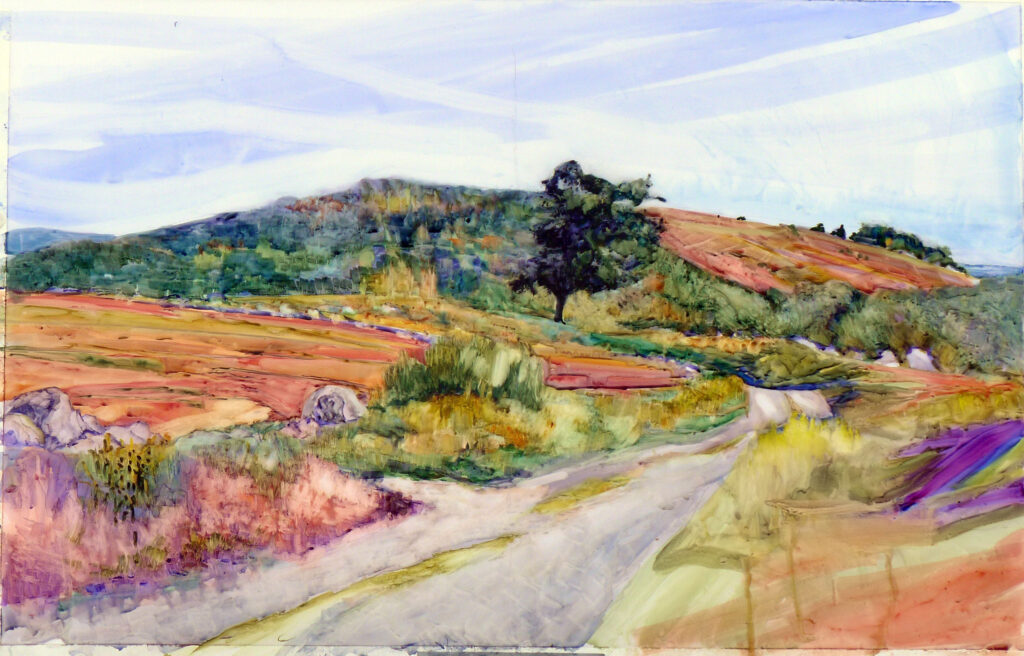

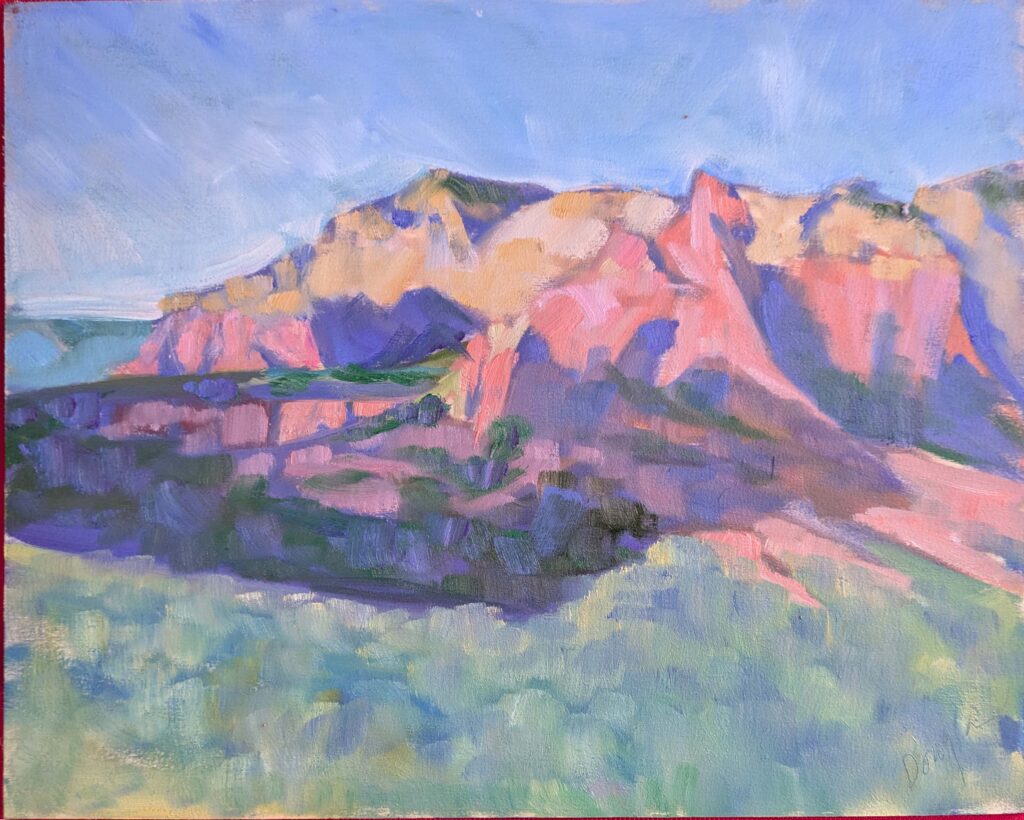

There is something about Casey Cheuvront and Upper Red Rock Loop Road. Last year, a woman parked herself in front of Casey and gave her clients a long spiel about the magnetic energy of the rocks, while rolling magnets around on a metal plate. Another guide occupied the same spot to talk about ley lines. It’s distracting to have people looming in front of you, obscuring the view.

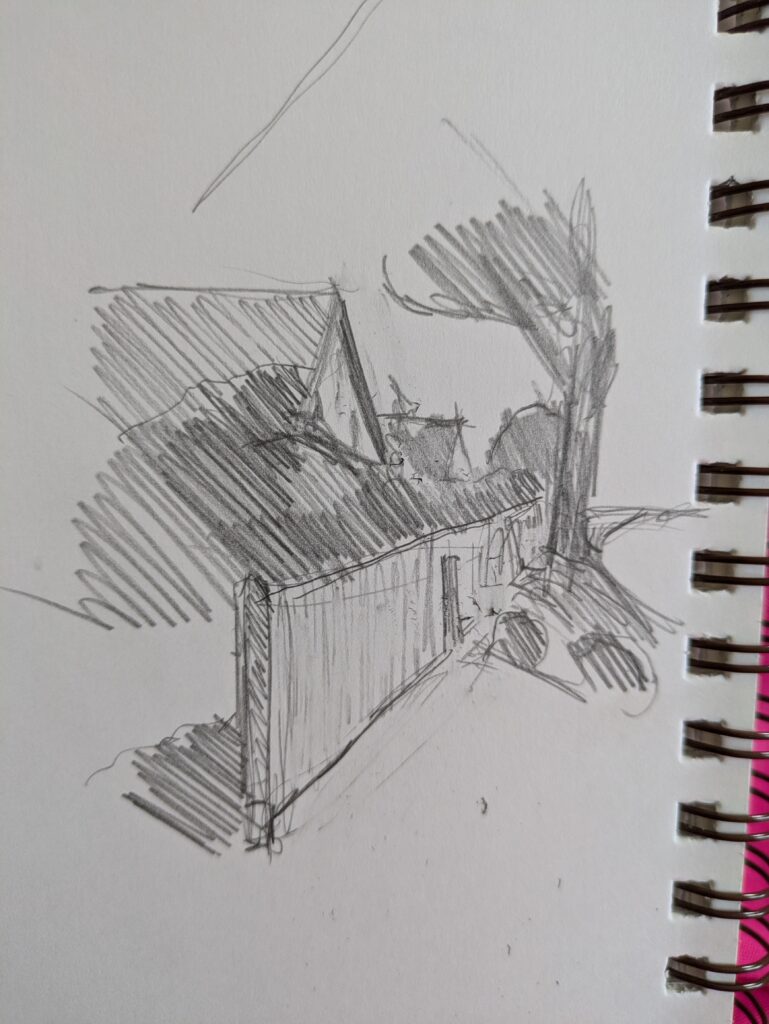

On Saturday evening, Casey, Ed Buonvecchio and I set up to paint the sun dropping over Sedona. We were careful to follow the etiquette of a plein air festival, which includes:

- Respect the venue, and follow any rules;

- Don’t disturb others’ enjoyment of the natural surroundings;

- Don’t plant yourself in the middle of a path;

- Clean up after yourself;

- Engage with interested passers-by;

- Be considerate of other artists. This means giving fellow artists space to work, and not getting in their sightlines.

Casey was tucked into the shadow of a juniper, painting the sunset. A swarm of photographers suddenly surrounded her. It was a workshop. Despite there being tens of thousands of acres of open land around us, and paths leading in every direction, they were packed so tightly around Casey that she didn’t have room to move.

“Do you mind?” the instructor asked. “We’ll only be a few minutes.” Forty minutes later, they finally shoved off, but the light, and the moment, had passed.

It all starts with drawing

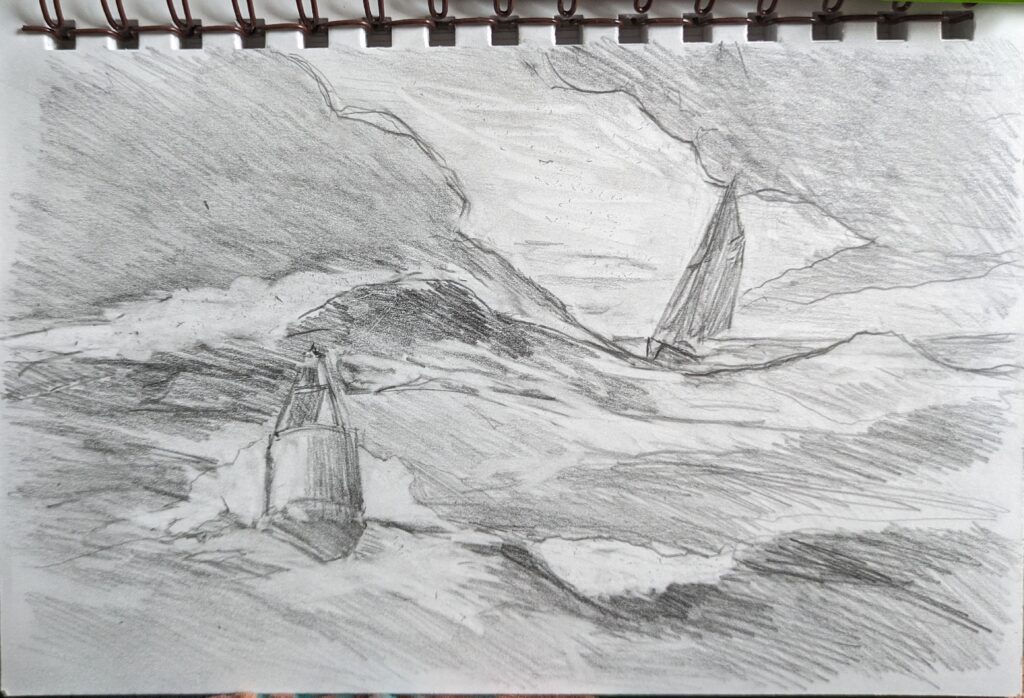

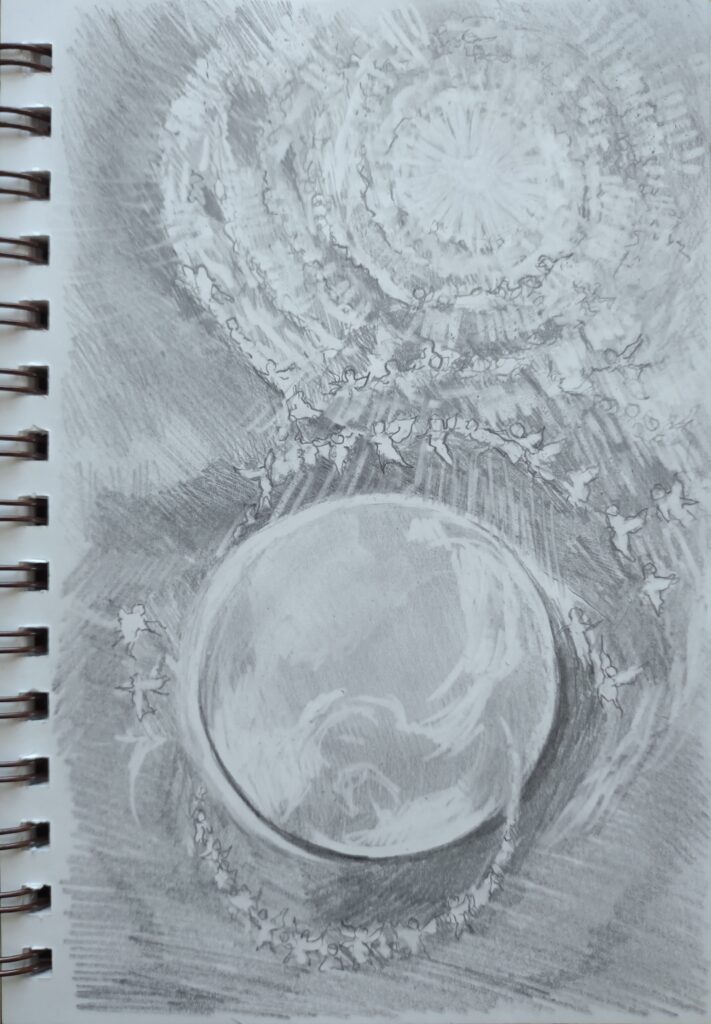

“You don’t always do a value drawing, do you?” Ed asked me. On the rare occasions when I skip one, I regret it.

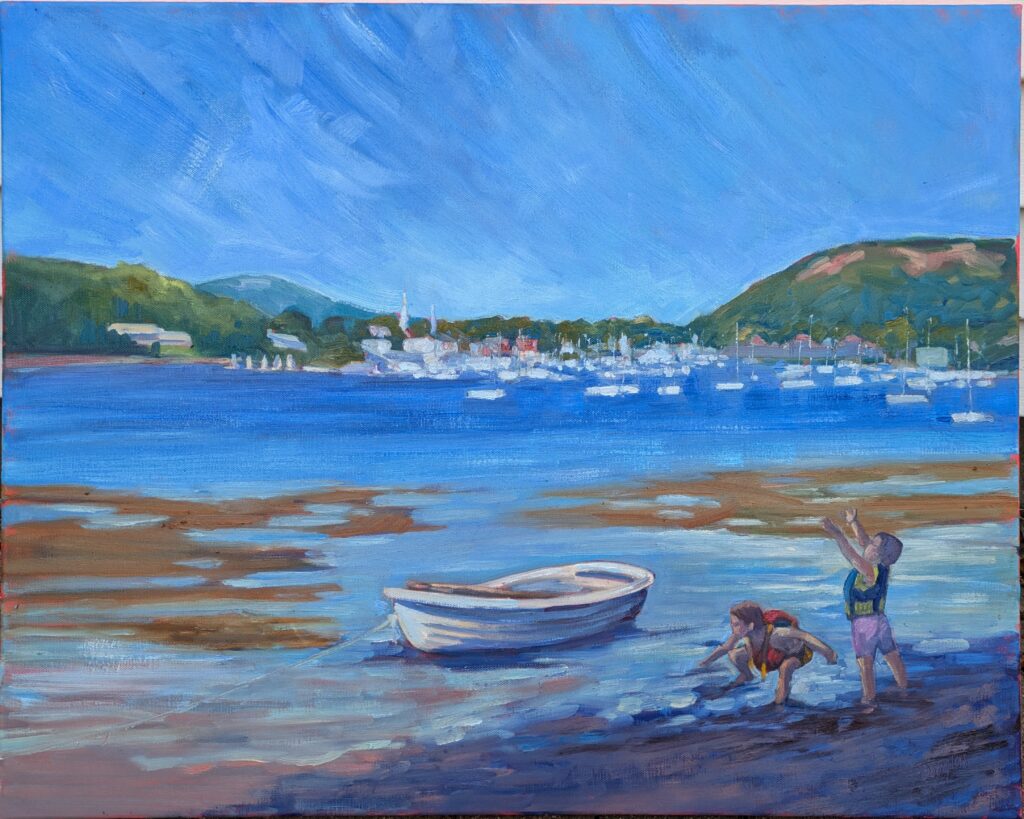

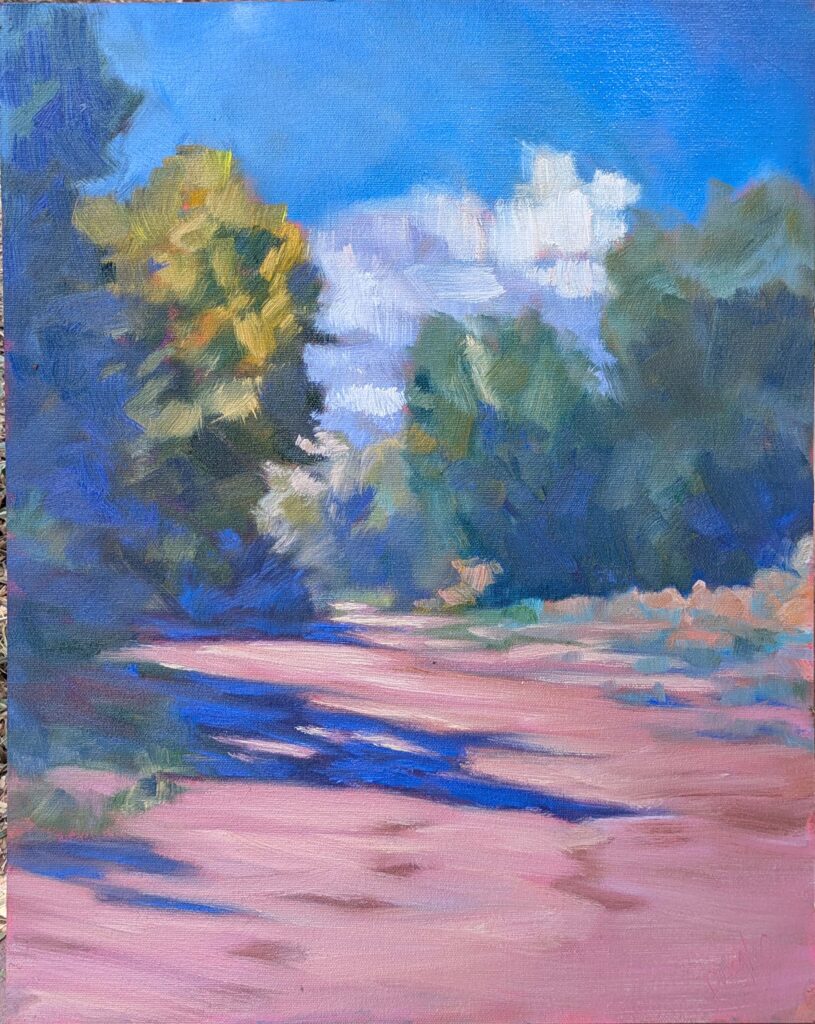

I’ve been going out at 6 AM to paint the dawn. In two days, I’ve done several sketches and gotten my final idea transferred to canvas. (I still have some foreground issues to work out.) My canvas is gridded because, yes, I do a value drawing and then transfer it to my canvas.

That proved very handy last evening as the shadows changed by the minute. I was able to reference my drawing when the light had gone. When you think you don’t have time for a value drawing is when you need it most.

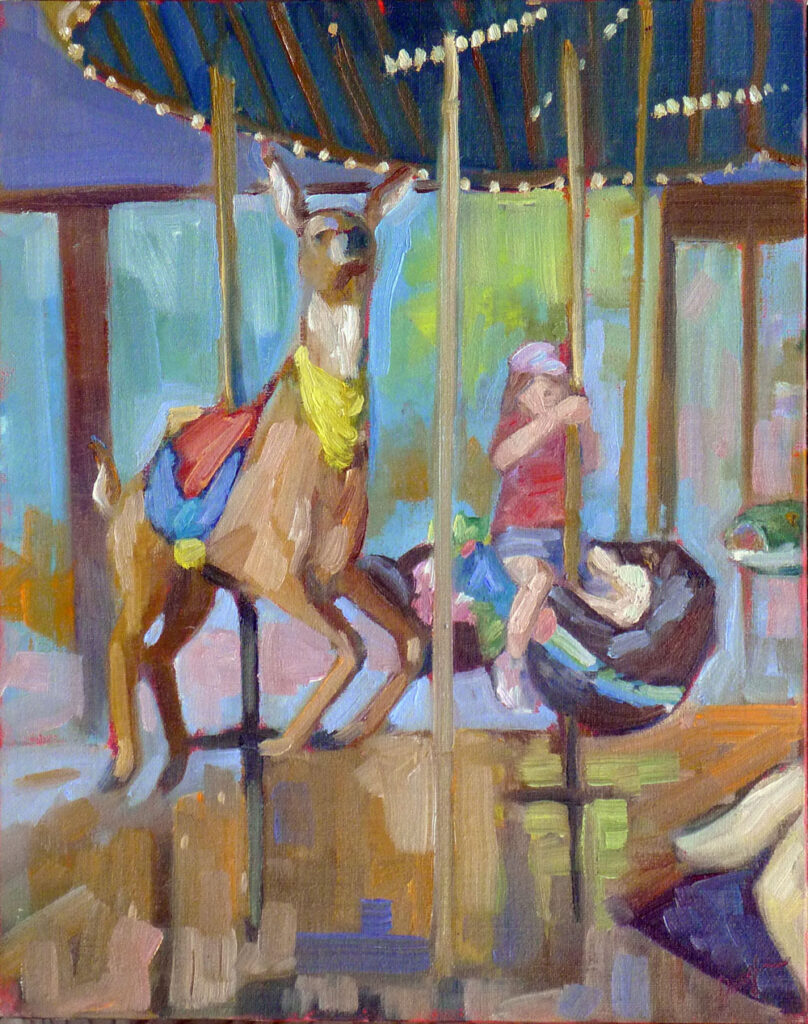

Show ponies

Hadley Rampton and I were sitting on a fence watching the scrum at our first quick-draw. “I think plein air festivals are like the rodeo,” I mused. “We all know each other, we all go around the same circuit, we compete for the same prizes.”

“I’ve thought about that,” she responded, “but I think we’re more like show ponies.”

And on that note, I’m off to paint the dawn again. I’m sorry these missives are so brief, but plein air festivals mean long days of painting.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

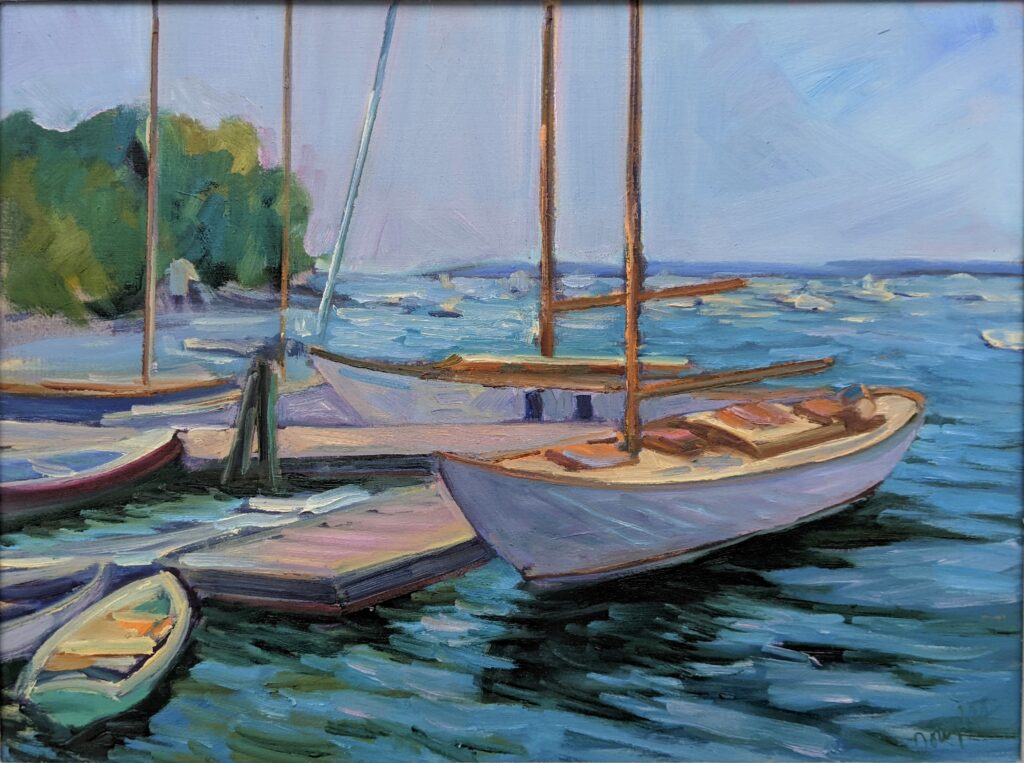

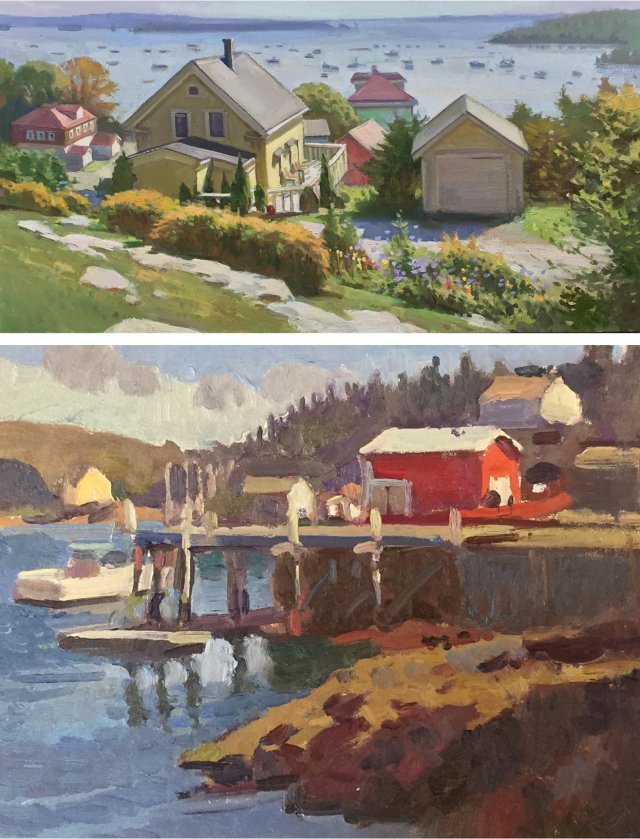

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

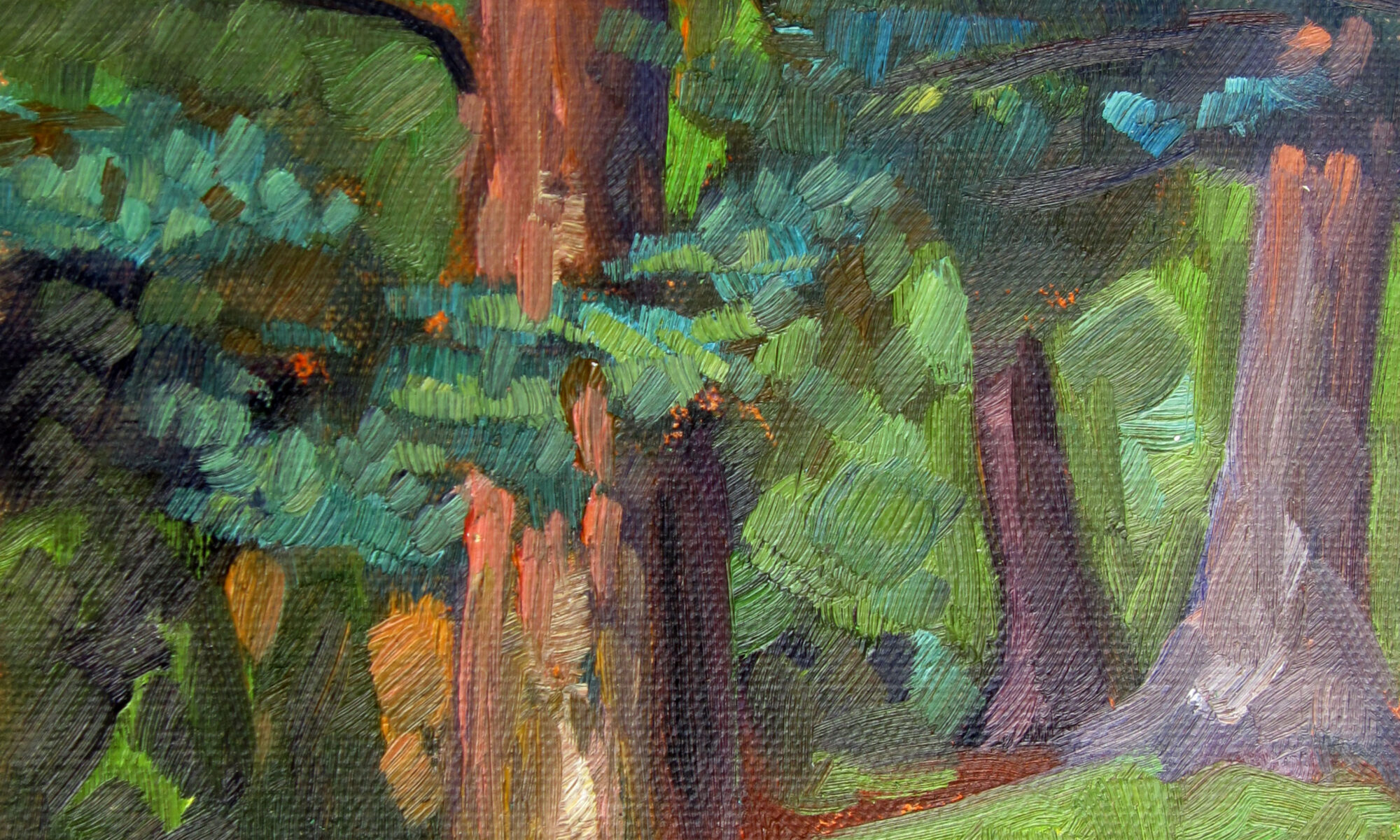

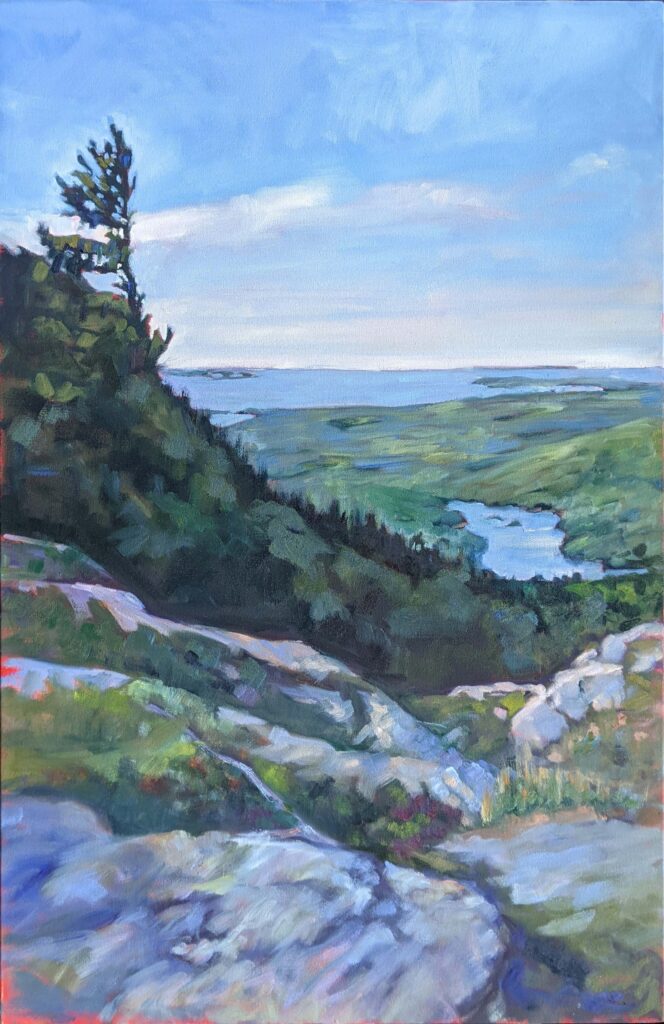

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.