No, not the G7—that’s the forum of world’s biggest economies. They’re politically important, but nowhere near as important as the Canadian painters by that name.

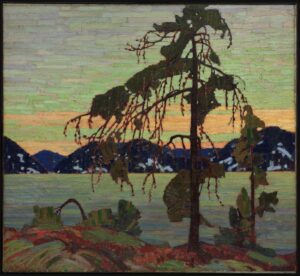

- The death of Tom Thomson is one of art’s enduring mysteries. Although the Group of Seven didn’t formalize until after his death, he was one of the painters who gathered at the design firm Grip, Ltd. He was arguably the most famous of them all.A dedicated woodsman and fisherman, he loved heading into the wilds of Algonquin Provincial Park to paint, as he did one July afternoon. He was found drowned eight days later, a four-inch bruise on his temple. Did he capsize, did he commit suicide, or was he murdered by a jealous husband? We’ll never know.

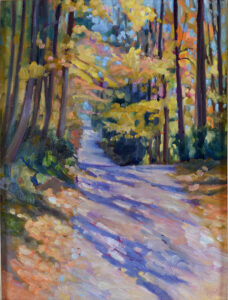

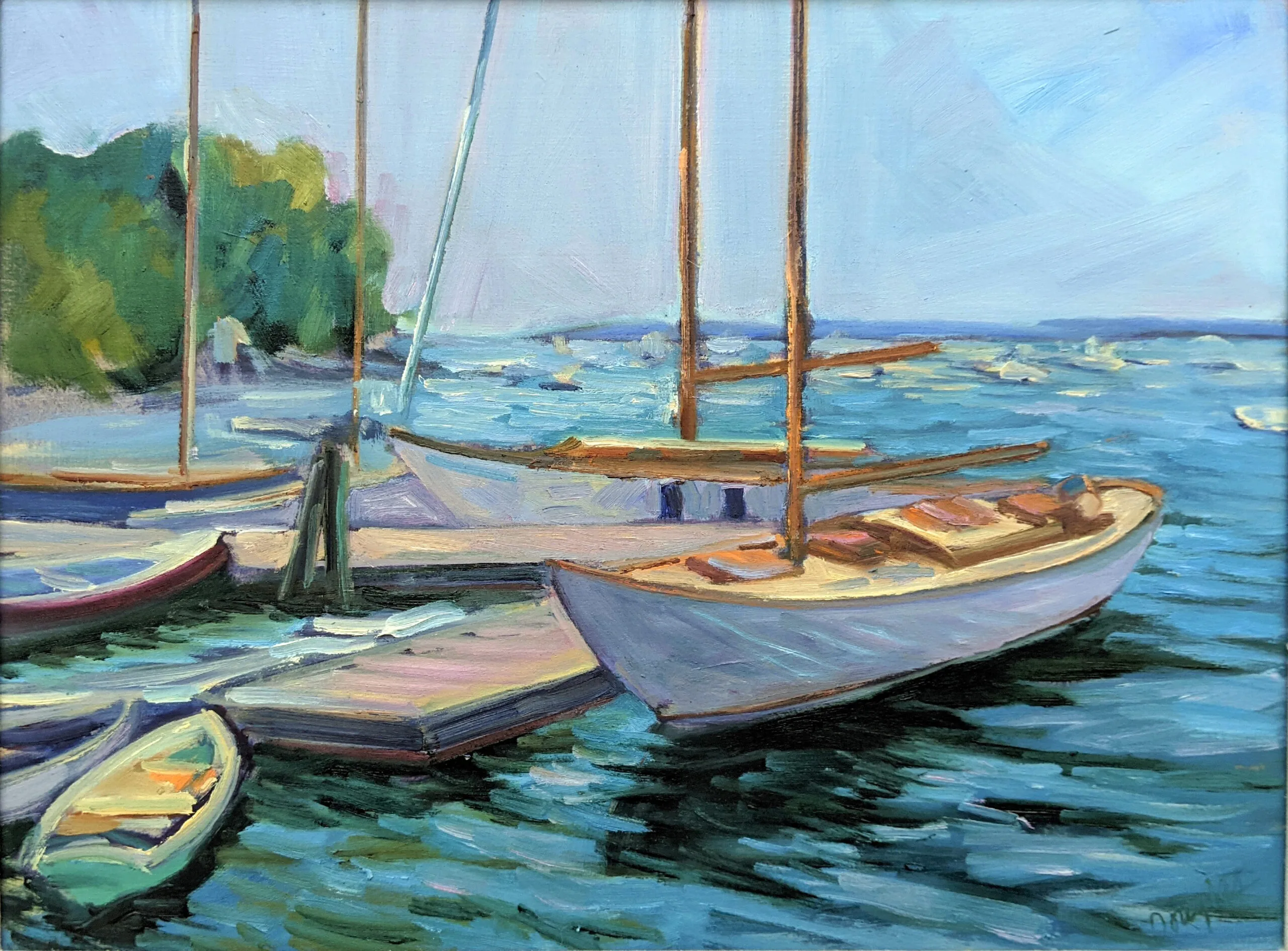

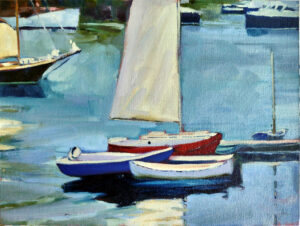

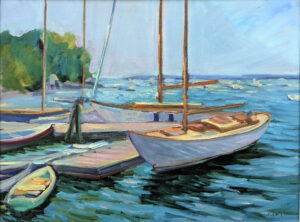

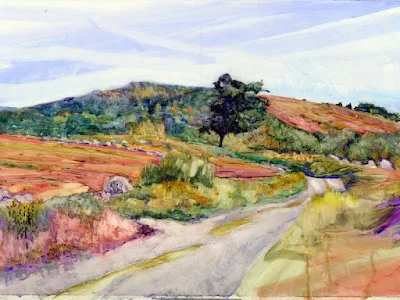

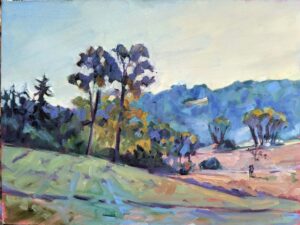

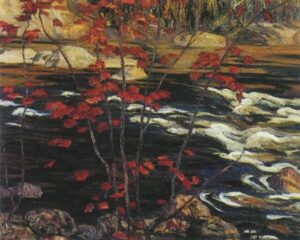

Red Maple, 1914, by AY Jackson, courtesy National Gallery of Canada - The Group of Seven were realists in the age of abstract art.They passionately clung to plein air in defiance of a world culture that was veering off toward abstraction. They felt the spirit of Canada was best understood by painting in direct contact with nature. Instead of huddling in Toronto studios massaging their angst, they rode the rails to some of Canada’s most desolate and difficult-to-reach spots.

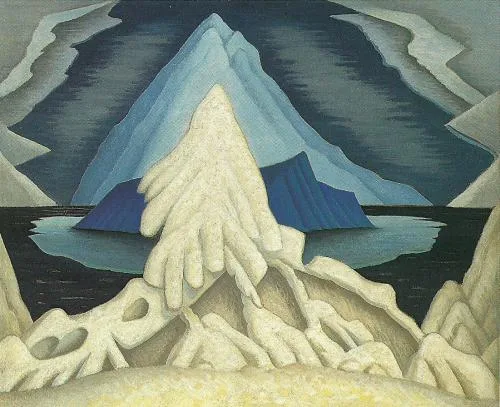

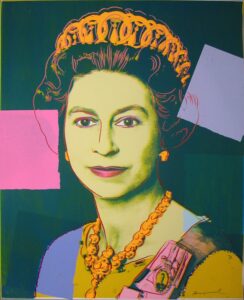

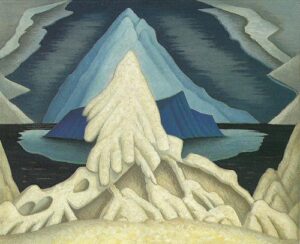

Winter comes from the Arctic to the Temperate Zone, 1935, Lawren Harris - They invented the idea of the Great White North.Lawren Harris believed the desolate north was the seat of Canada’s economic and spiritual power. His scenes of the cold, majestic, and empty northland defined Canada’s essential self-image. This was a land of black spruces, isolated peaks and dark water, lit by fantastic skies.This started out as nationalism, but transformed into a more universal paean to the power of nature. As much as he abstracted the landscape in later years, he always told this story.

Gas Chamber at Seaford, 1918, by Frederick Varley, courtesy Canadian War Museum - The Great War temporarily derailed them.The First World War had a profound effect on Canada. Out of an expeditionary force of 620,000, 39% were casualties. AY Jackson, Arthur Lismer and Frederick Varley enlisted as official war artists. Jackson served in France and was seriously injured. Lawren Harris enlisted in 1916 and was discharged in May 1918 after a nervous breakdown. Tom Thomson’s death in 1917 was another blow to the group.

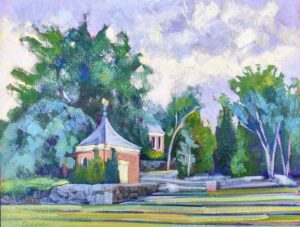

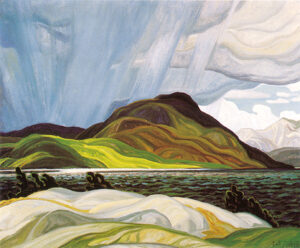

Lake Wabagishik, 1928, Franklin Carmichael, courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection - In the early years, the group was supported in part by tractor money.Lawren Harris was the son of Thomas Harris of A. Harris, Sons & Company Ltd., farm machinery merchents. This merged with the Massey company and later became known as Massey Ferguson. Harris's share of his family fortune enabled him to partner with James MacCallum to build the Studio Building in Toronto, where his fellows could rent studio space cheaply. Together the two men bankrolled the Group of Seven during lean periods. Harris took them on boxcar trips to Algomaregion north of Lake Superior and elsewhere.

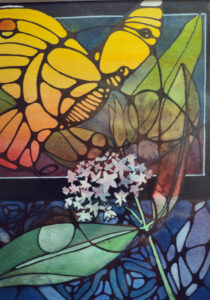

A Northern Night, 1917, Franz Johnston, courtesy National Gallery of Canada - They developed a distinctive Canadian style.Group of Seven paintings are instantly recognizable by the fusion of graphic design and Impressionism. However, they were always driven by what was actually there. The screen of trees and the view down into the deep woods are recurring motifs. This is not a grand, golden view in the style of the Hudson River School painters, but a deeply honest view of what the northeastern part of North America looks like. It requires embracing chaos in a totally new kind of composition.

RMS Olympic in dazzle at Pier 2 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Arthur Lismer, courtesy Canadian War Museum - The Group of Seven is not without controversy.They’ve been criticized for depicting northern Canada as a no-man’s-land, or terra nullius, when it’s been lived in for centuries by indigenous people. However, the goal of plein air has primarily been to capture the landscape, not human activity.Having painted across Canada myself, I can say that much of it seems empty a hundred years later. In any case, they’re among the best painters North America has produced, and that’s the real reason to study their work.