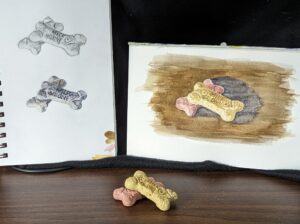

On Wednesday, I mentioned our late Jack Russell Terrier (or Terror, depending on the day). Above all, Max was a fearless hunter, a skill that often got him in trouble. He was capable of snatching a songbird in midflight, and squirrels and chipmunks stayed away when he was outdoors.

Sadly, he seldom got an opportunity to exercise that skill in a positive way. However, he’d periodically grow restive, whining and pointing at some blank section of wall. I learned to recognize that as a sign we had invaders in the house. Most commonly they were mice, which are easily dispatched. Memorably there was once a rat behind the dishwasher.

It was an old house with nearly a century’s worth of paint on the moulding. One day I noticed that a cold air return was shining silver. It had been licked and chewed clean. “Oh, dear, it’s lead paint,” I thought. “Max is going to lose whatever little sense he started with.” I watched him carefully and realized he spent his whole day hanging around that duct.

Then I opened the basement door. Max flew down ahead of me. There was an opossum on the top of a shelving unit where we stored extra glassware, appliances and other things that no longer brought us joy. Max went berserk trying to climb the shelf. The opossum retaliated by throwing things down on Max. Together they made a terrible mess. The good news was, I had lots less to get rid of when it came time to KonMari my life.

At the time, we had a young lady named Abi living with us. Abi really, really wanted to keep the opossum. “They make good pets,” she insisted. I might have tried had Max and Mr. Opossum not been sworn enemies. Plus, he had very sharp-looking teeth, and opossums have opposable thumbs on their hind legs. That could only lead to trouble.

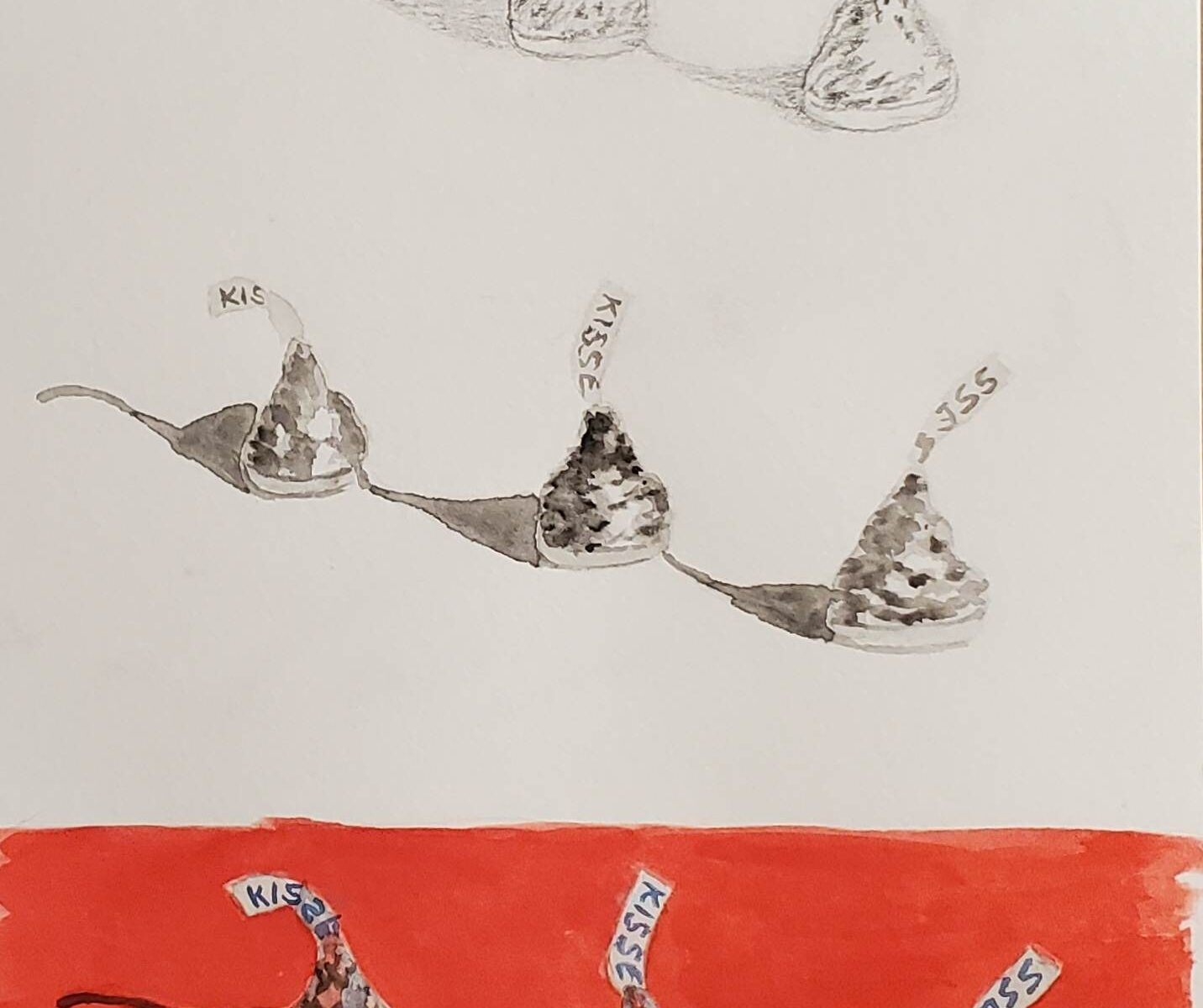

For a while, it was a stalemate. We put delicacies in a trap; he ignored them, or worse, fished them out. It was nearly Thanksgiving and I kept my pie plates in the basement. That’s how I finally won. Mr. Possum found my piecrust irresistible. (The recipe is here.)

Our good friend did not go gently back to nature. We drove him to a county park on the other side of the Genesee River, which is wide, deep and fast as it enters Rochester. He didn’t like the idea and hissed all the way. With one final scowl in my direction, he ambled off into the shrubberies. I’m not sure Abi has ever forgiven me.

My 2024 workshops:

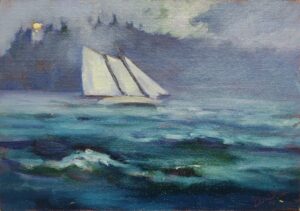

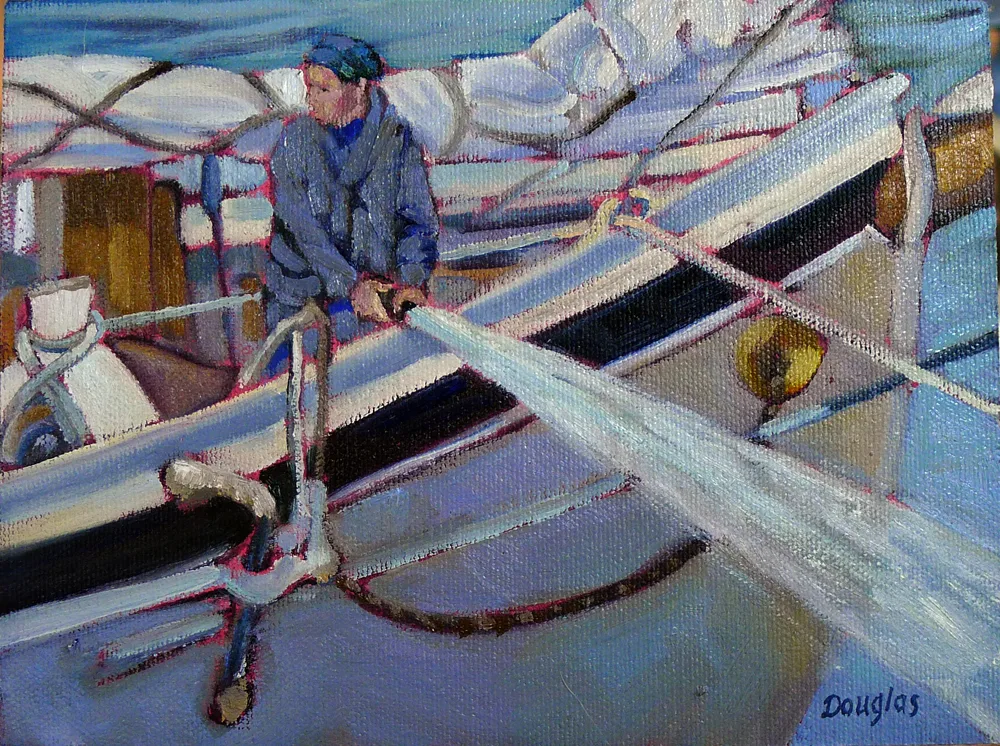

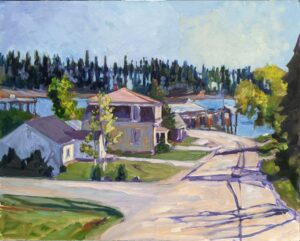

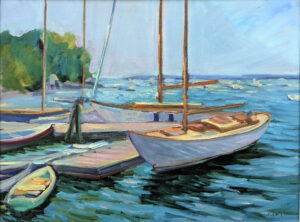

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.