Last week in my Color of Light class, the conversation turned to water-miscible oils. I haven’t used them in years, and only to test them to see if they were a reasonable alternative to conventional oils (yes, although I don’t like their hand-feel). It’s your turn to teach me, and answer the question raised by my students: do miscible oils hold up over time?

Several of my students described problems with cracking, inner layers that didn’t cure, paint surfaces sticking to other things, or paint softening after varnishing with Krylon Kamar Varnish. “But the color is so much better when the painting is varnished,” said the person who’d used the Kamar.

Since I’m a novice on the subject, I’m hoping that those of you with extensive experience with water-miscible oils can share that, good or bad

Kamar is, according to its material safety data sheet (MSDS), full of solvent. At least two of these—heptane and acetone—can dissolve oil paint, so I’m not shocked that Kamar could loosen up the surface of a painting. I’m no chemist and I’m not interested in reading MSDS for every spray varnish, but it makes sense that spray varnish needs plenty of solvent to be sprayable. On the other hand, I’ve used spray damar varnish on conventional oil paintings with no softening of the surface.

Winsor & Newton makes a line of brush-on varnishes for their water-miscible oils, in matte, satin and gloss. I recommend my student try one of those.

Miscible oils are oil paints that are engineered to allow them to be thinned and cleaned up with water. The idea is to avoid using volatile organic compounds like turpentine, which are harmful when inhaled. A disclaimer, however: we haven’t been using turpentine as a solvent in this country in this century; it’s been replaced with odorless mineral spirits, or OMS. In a sense, miscible oils are fixing an obsolete problem.

The typical way of making oil and water mix is to add a surfactant. That’s how detergent works to remove oils from your clothes and dishes. For water-miscible oils, the end of the oil medium molecule is rejiggered to help it bind loosely to water molecules. The key here is loosely; you want the water to evaporate.

The top-tier oil paint manufacturers, such as Gamblin or Michael Harding, do not offer miscible oils. Rather, they have solvent-free systems for working with regular oils. To me that indicates that miscible oils cannot yet be made to the highest standards of oil paints. In fact, the biggest complaint I hear about miscible oils is that their pigment load is lower. I don’t have enough experience to answer this with authority. Do you?

The issue of paintings not setting up or cracking is far more serious. This may be a simple fat-over-lean question. (I think that’s why my Kamar-using student’s paintings were dull and lifeless in the first place.) Fat-over-lean is every bit as true for miscible oils as it is for conventional oils.

In addition, miscible oils can crack is too much water is used, for the same reason that acrylics degrade if excessively diluted. There must be enough medium present to form a bond.

That’s all I know about the subject, so I’d love to hear from you painters with experience with miscible oils: do you like them? What problems have you had with them? Do you have paintings a decade or more old, and if so, how is the finish holding up?

My 2024 workshops:

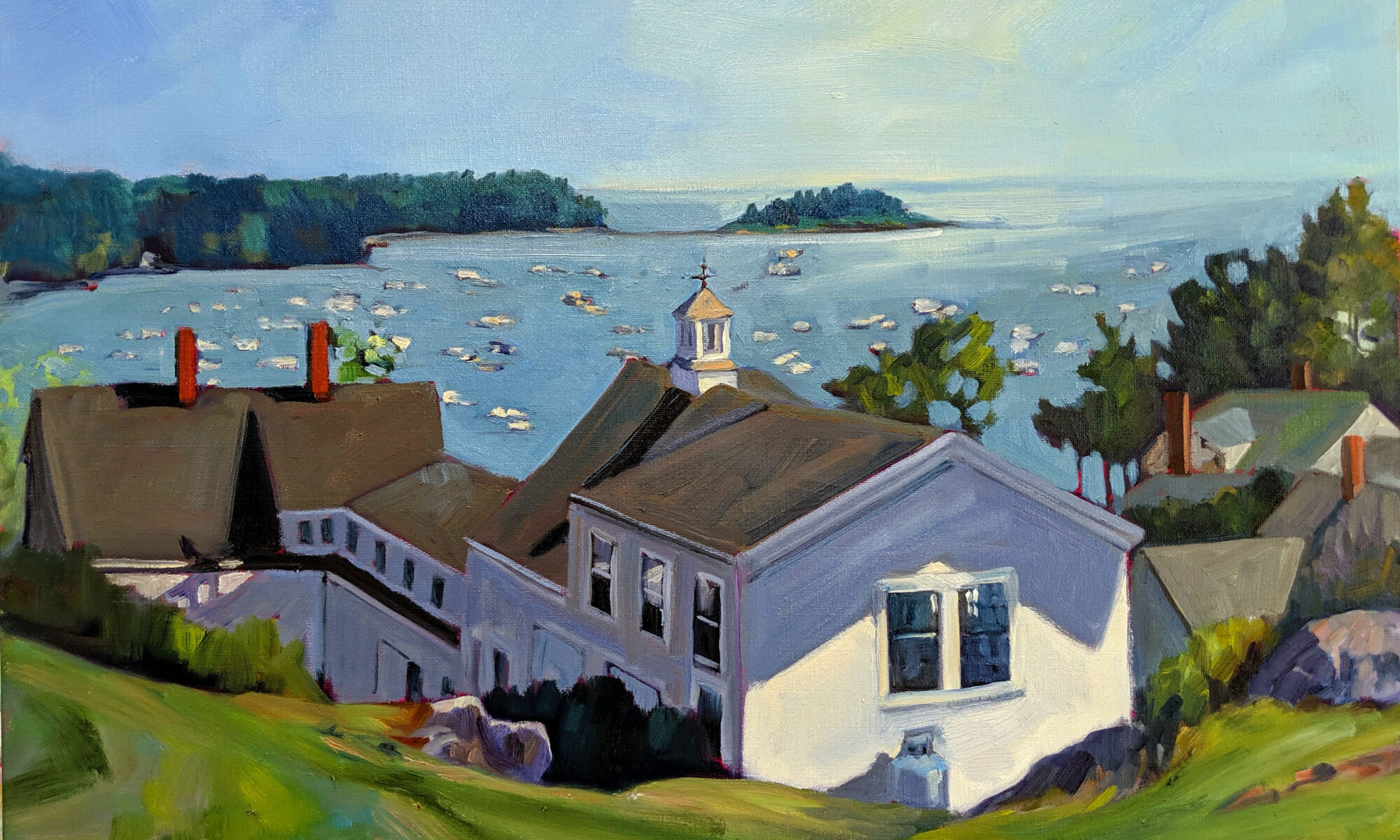

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

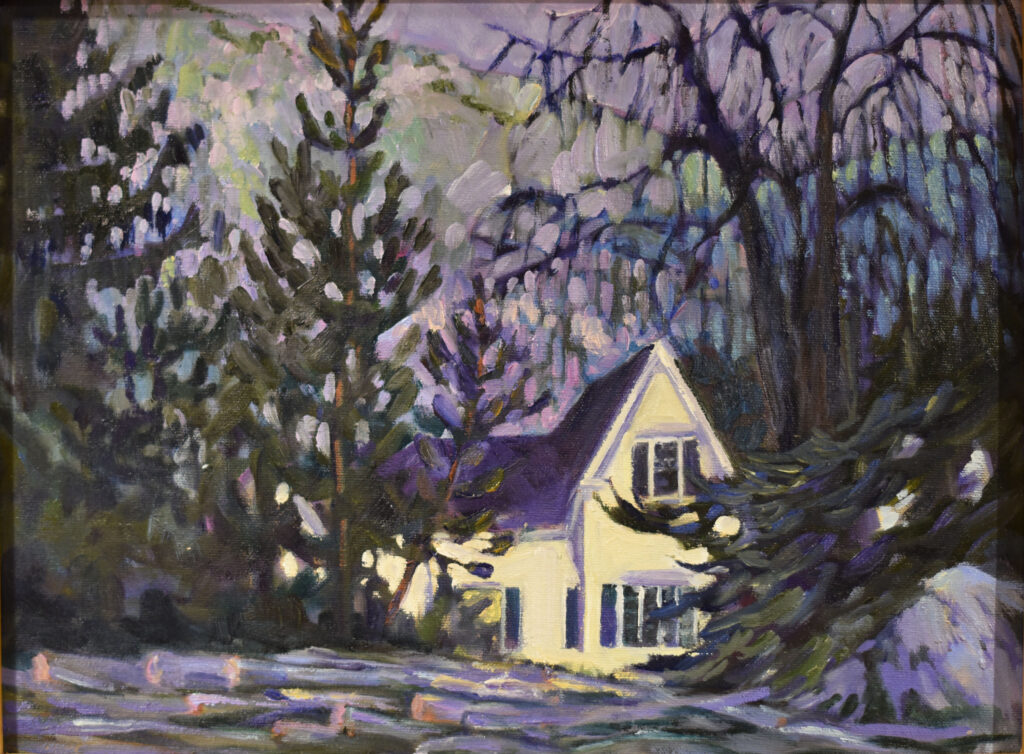

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.