I’ve got a student who’s been waiting for a chip for his GM pickup truck for several months. “First world problem,” he says good-humoredly when I ask him about it. I get that he means it as an expression of gratitude that his problems aren’t bigger, but it’s an expression that bugs me. It rests on a logical fallacy. First-world problems are not inherently less-important than those of the developing world.

Yes, food poverty is an extreme and crushing problem, but so too are fatal drug overdoses. Affluence increases longevity, but it’s not a strictly linear relationship; otherwise, Bangladeshis (averaging 72.1 years) would not outlive Indians (averaging 69.7 years).

Obviously, I can’t speak for the developing world, but I doubt their lives are characterized by endless misery and suffering. We all have our joys and sorrows, big problems and trivial ones.

A vehicle, a reader chastised me recently, is not a necessity. “High gas prices are a good thing. We should walk more and use public transportation,” she wrote. I don’t know where she lives, but that’s not practical for most of us. Even those who live in large cities rely on internal-combustion engines. Everything they consume is delivered by truck; their trash is invisibly whisked away in trucks. Subway trains and busses are, overwhelmingly, diesel. Food is grown on farms, using tractors, powered by diesel.

A truck sitting at a dealership, undriveable, represents something more than inconvenience. It’s a major financial asset that’s depreciating without being usable. It represents trips that can’t be taken and work that cannot be done. For the dealership, not finishing the job means lost productivity.

Multiply that by 95,000 GM vehicles sitting on lots without chips, and we’re talking about billions of dollars of lost revenue. That will inevitably translate to laid-off workers. And that’s just one car manufacturer.

“First world problem” is sometimes used as a comical apology about trivial concerns. In this sense, it’s a humblebrag, since it points out that you can afford $5 for a cup of coffee in the first place, or to lose another set of AirPods. It’s checking your privilege before someone else has the chance to check it for you, and that’s where it gets really ugly.

If you complain that you spent two hours in a security line at an airport and missed your connection, and someone responds “first world problem,” they’re really just saying “STFU; I don’t care about your troubles.” Travel problems are very real; 4 out of 5 travelers this year are reporting some kind of disruption.

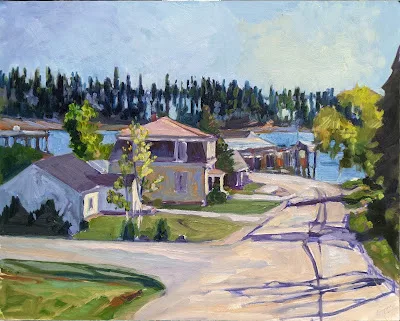

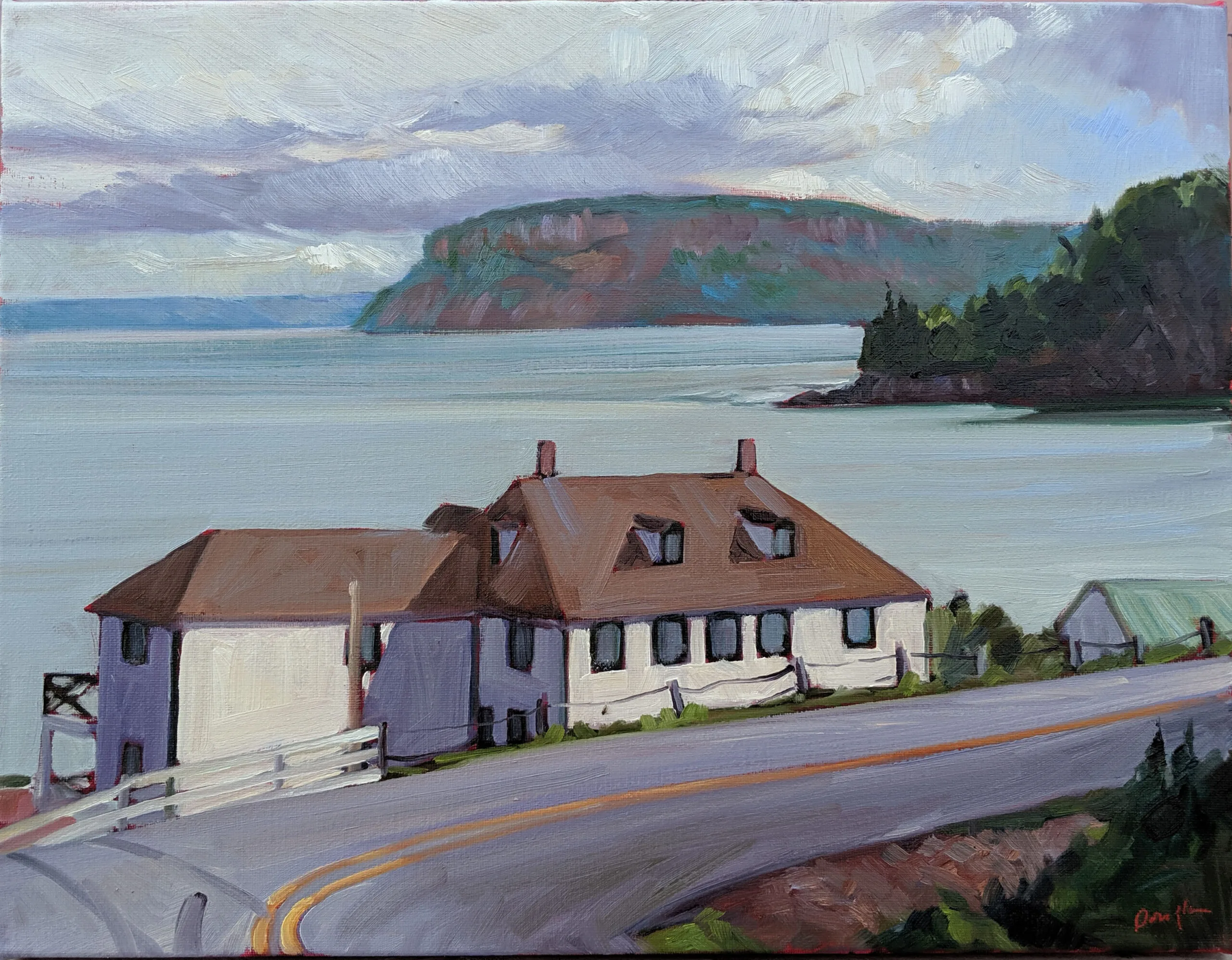

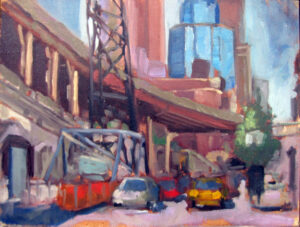

Artists are the canaries in the coal-mine of the economy, as aesthetics are pretty high on the hierarchy of human need. I’ve worked through six recessions, and they’re no fun. We’re not in one yet, but we’re in a period of economic turmoil. We’re seeing all kinds of fallout in the art business this summer. Dismiss this as a first world problem if you want, but please don’t say it within my earshot.

.jpg)

.jpg)