I used to be a terrible abuser of paintbrushes. That’s a bad mistake, because brushes are expensive. If I wasn’t forgetting them in my plein air pack, I was dropping them overboard. And although I spent lots of time while cleaning them, I seldom managed to get them completely clean.

I’m reformed now, ever since my daughter Mary started making brush soap for me.

Before I talk about how to clean a paintbrush, let’s talk about what you shouldn’t do to them.

The Seven Deadly Sins of Paintbrushes:

- Not cleaning brushes immediately after use.

- Not cleaning all the paint out of your brushes. Cleaning is easy for watercolorists, but with oils it means making sure the paint deep inside the ferrule is removed, or the brush will splay. That’s not fixable.

- Using anything but clear, cool water to rinse your watercolor brushes. They don’t need or like soap.

- Letting brushes stand in solvent or water while painting. It’s not just bad for your brushes, it’s bad for your technique.

- Using brushes to scrub, dab, or any other motion that puts undue pressure on the bristles.

- Storing brushes in a way that distorts their bristles.

- Mixing oils and acrylic paints with a brush rather than with your palette knife. Not only do you not mix enough paint, mixing with a brush forces paint up into the ferrule, where it is hard to remove.

How to clean a paintbrush

Watercolorists have it easy. Simply rinse in clear, cool water, shake out the excess water, wipe down the handle, shape the bristles with your fingers and allow the brush to dry before putting it back in its case.

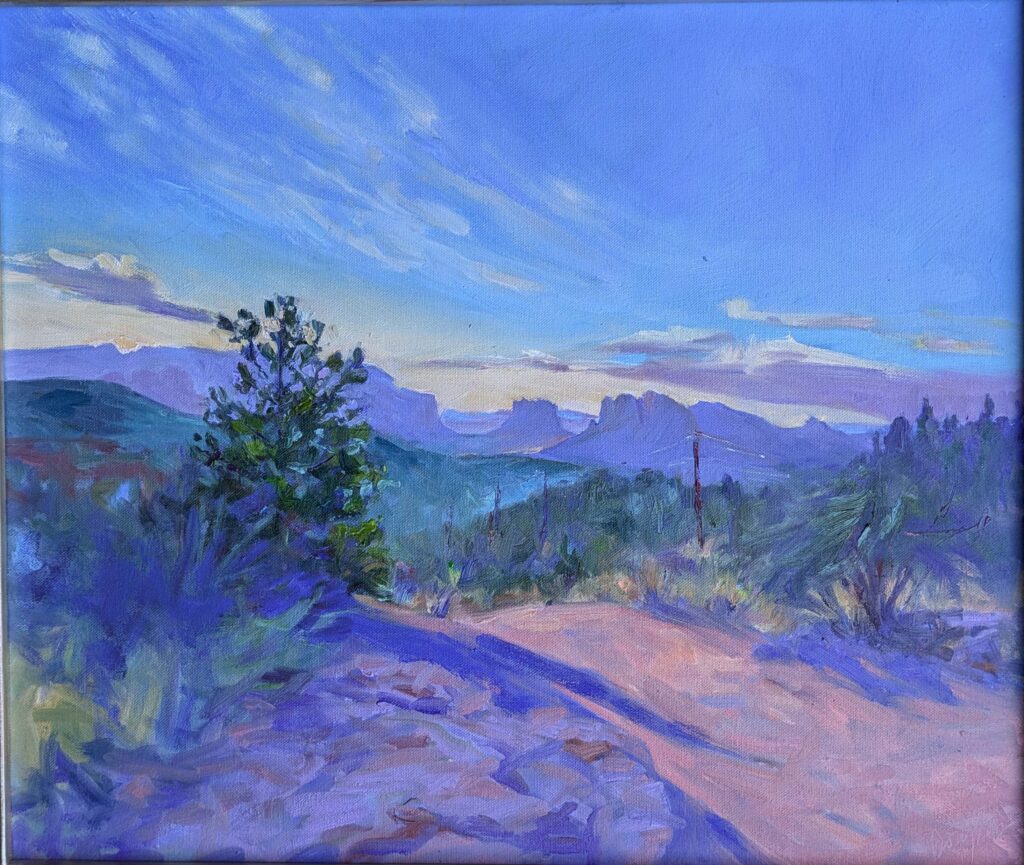

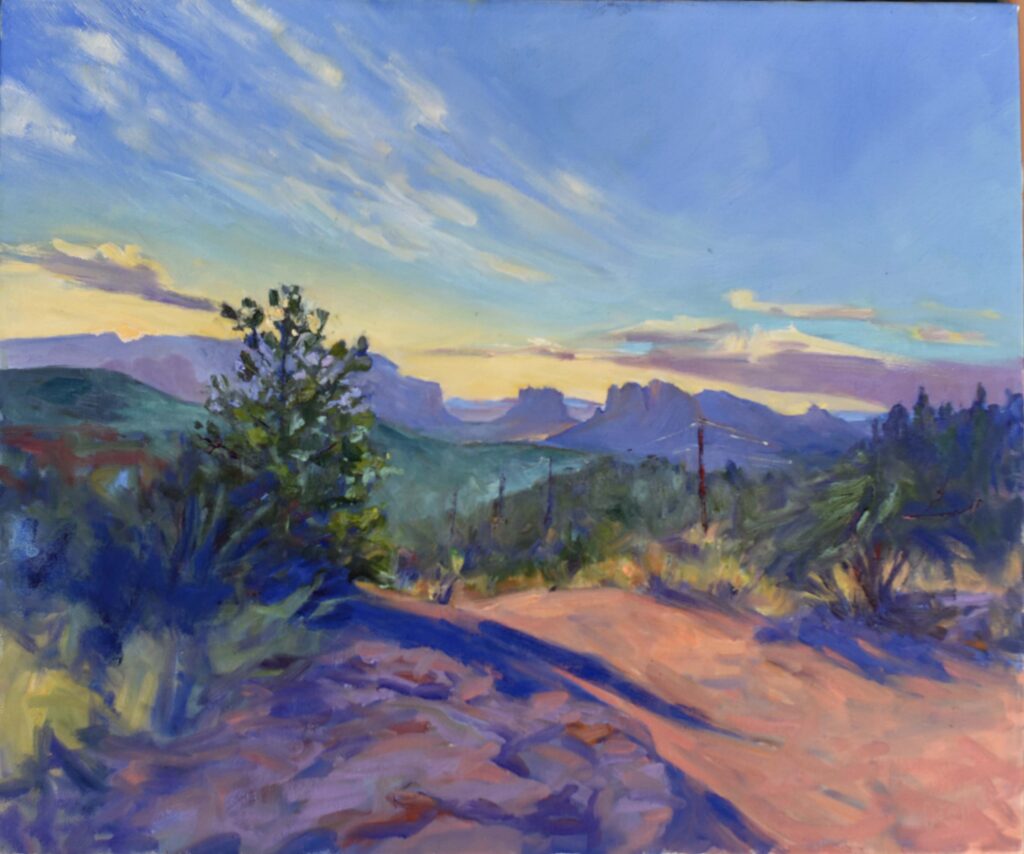

For oil painting, it’s easier for me to just show you:

Can you wash paint brushes in the sink?

“Will cleaning oil painting brushes clog up my sink?” a reader asked. I addressed that question in the above video, but the short answer is, you must remove all the solids from your brush with odorless mineral spirits (Gamsol or Turpenoid) first. If you do that, you’re fine. Otherwise, the soap and oil paint will form a thick emulsion that can, indeed, clog sinks.

A word about Rowan Branch Brush Soap

Our Rowan Branch brush soap is a vegan, oil-blend natural cleaning agent. It includes coconut oil, which I’ve found to be a particularly effective brush cleaner. My daughter Mary makes it for me in small batches, and we’ve just restocked, so it’s now available again for mail order.

“Your brush soap is seriously great. Better than Murphy’s or the pink stuff from Jerry’s. I can always get a little more out with yours,” said Mark Gale.

Mary has a small shop (the room behind her kitchen) and for a while, we’d run out of stock. However, she’s resupplied our inventory, so you can order new brush soap now.

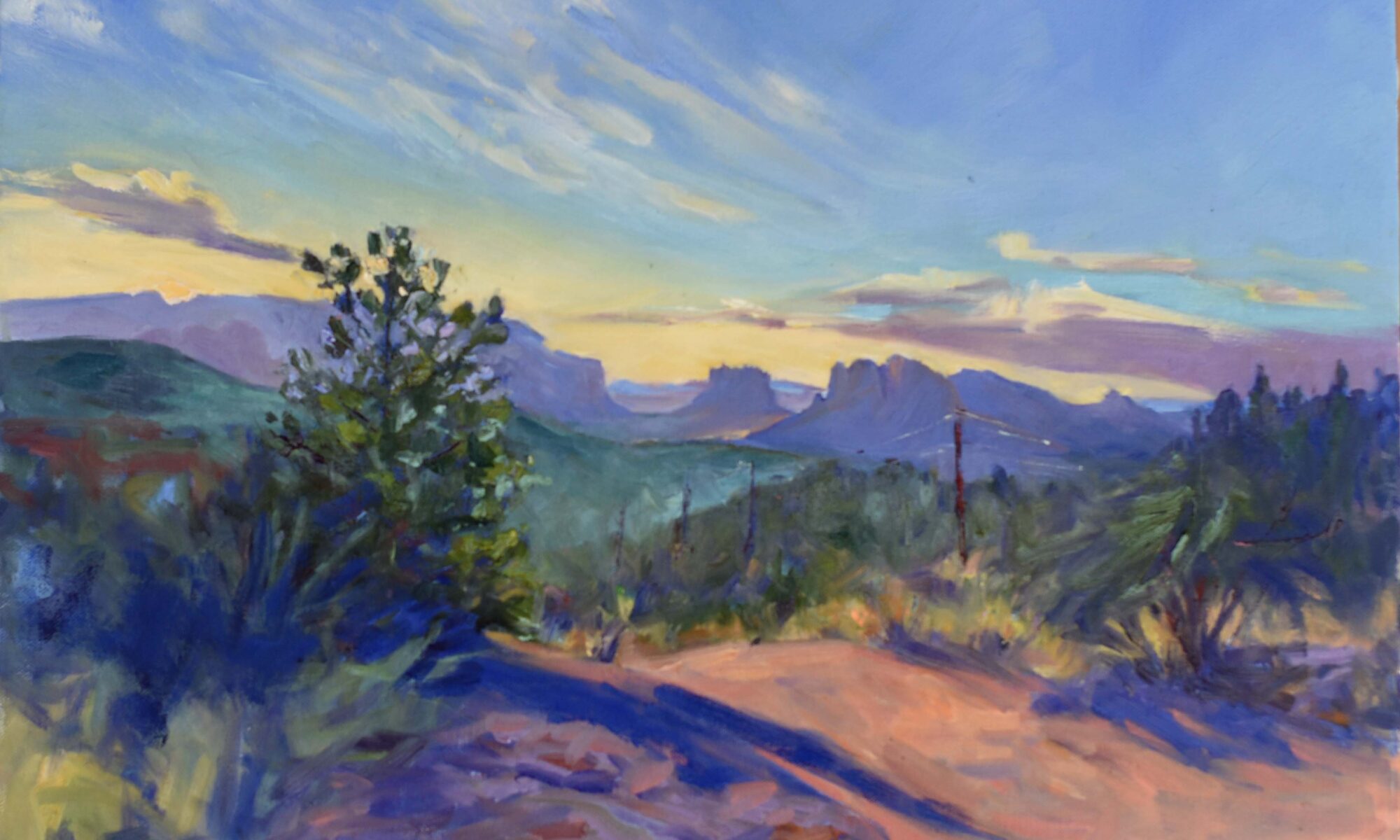

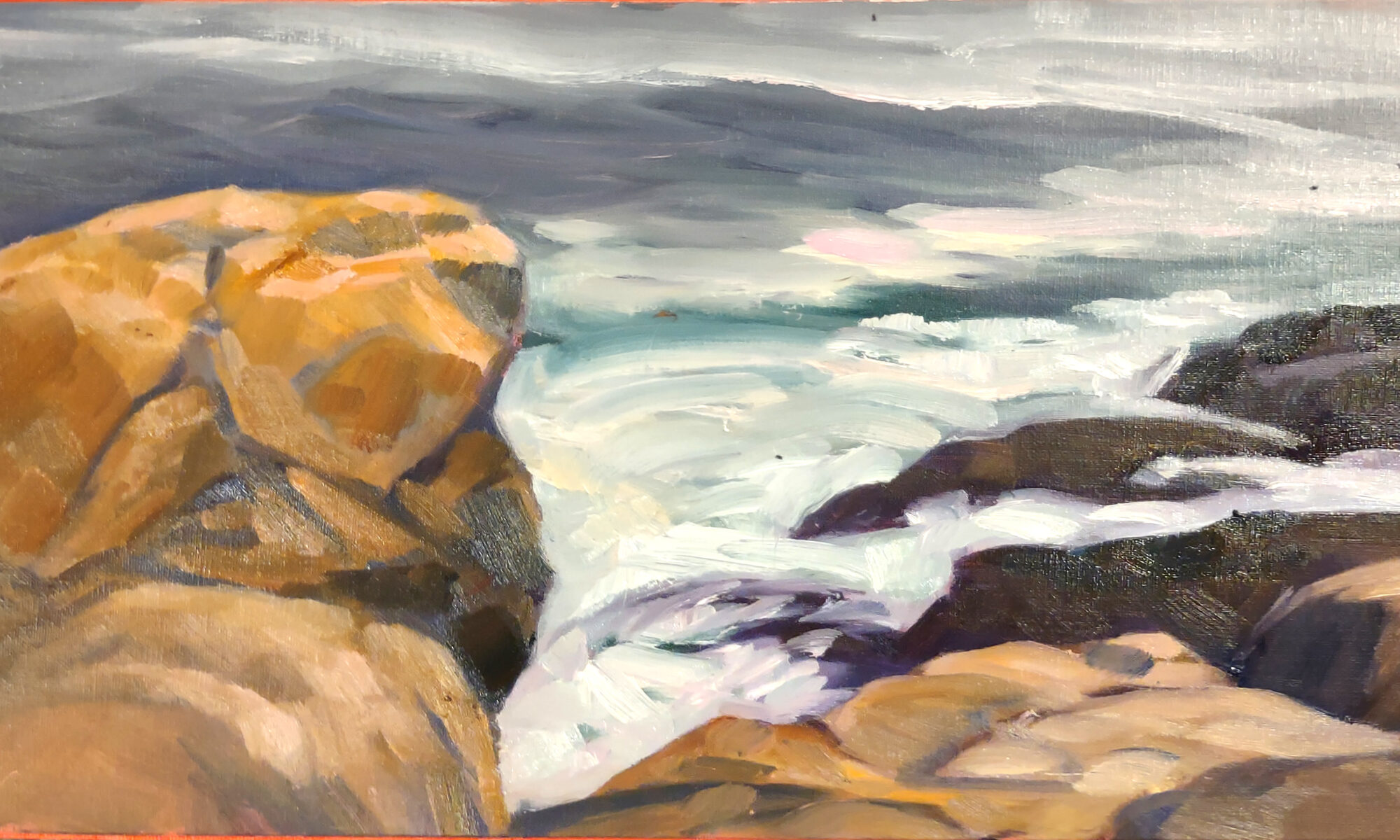

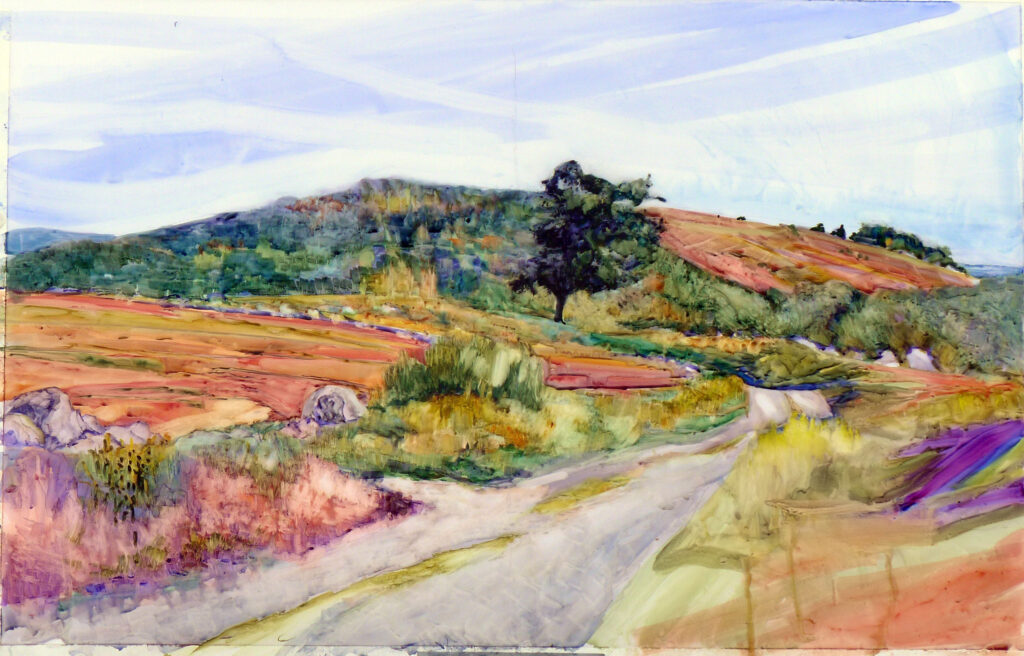

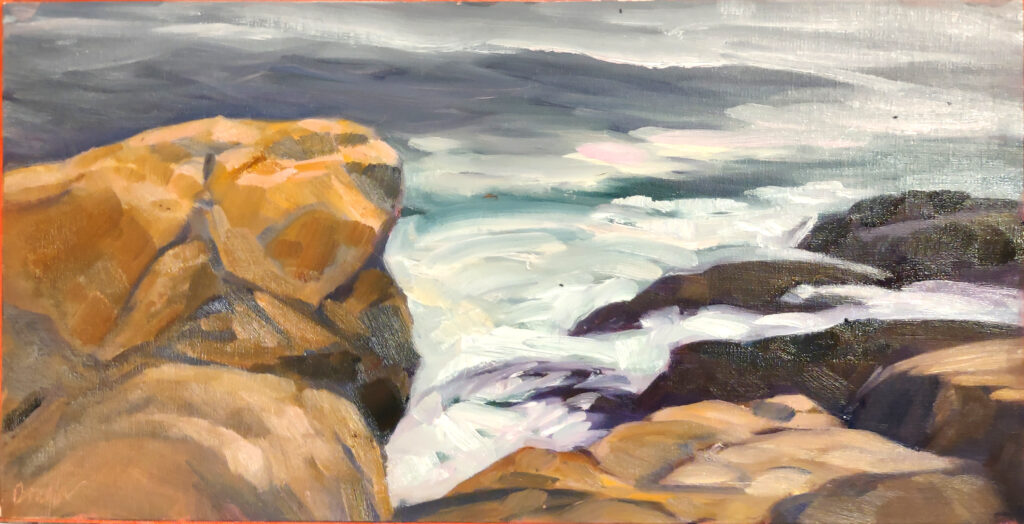

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.