My father was from the west side of Buffalo and my mother was born in the first ward of Lackawanna, NY. Although they were both thoroughly urban, they bought a farm in Niagara County, NY in 1965. We had cattle, horses, ducks, and a hundred feeder chickens every spring. It was a well-ordered farm when it was established in 1861, and it’s maintained its good bones right up until the present.

Although I couldn’t wait to get away, I realize now that the countryside was a great place to grow up. Most of my practical skills came from growing up on a farm.

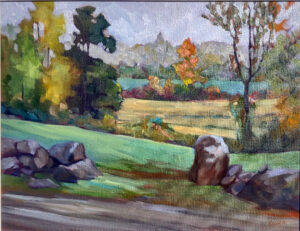

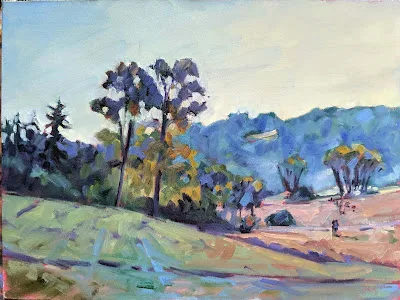

On Monday, I taught at Undermountain Farm in Lenox, MA. It’s got 23 horses, two sheep and two goats. The sights, the smells, and even the clatter of my shoes on the wooden barn floors were a powerful nostalgic kick.

Undermountain Farm’s horse barn has restrooms, a real step up from my childhood, where we had an external well with a pump that froze every winter. There are two horses at Undermountain Farm who are free to wander. As horses will, they really just want to scarf food the easy way. They found a broken bale directly under the hay chute, which happened to be directly in front of the restroom doors.

Their need was not greater than my need, but they outweighed me. I pushed their noses; they pushed back. Docile they might be, but they were blocking my way. Finally, I thought, ‘just move the hay.’ Problem solved.

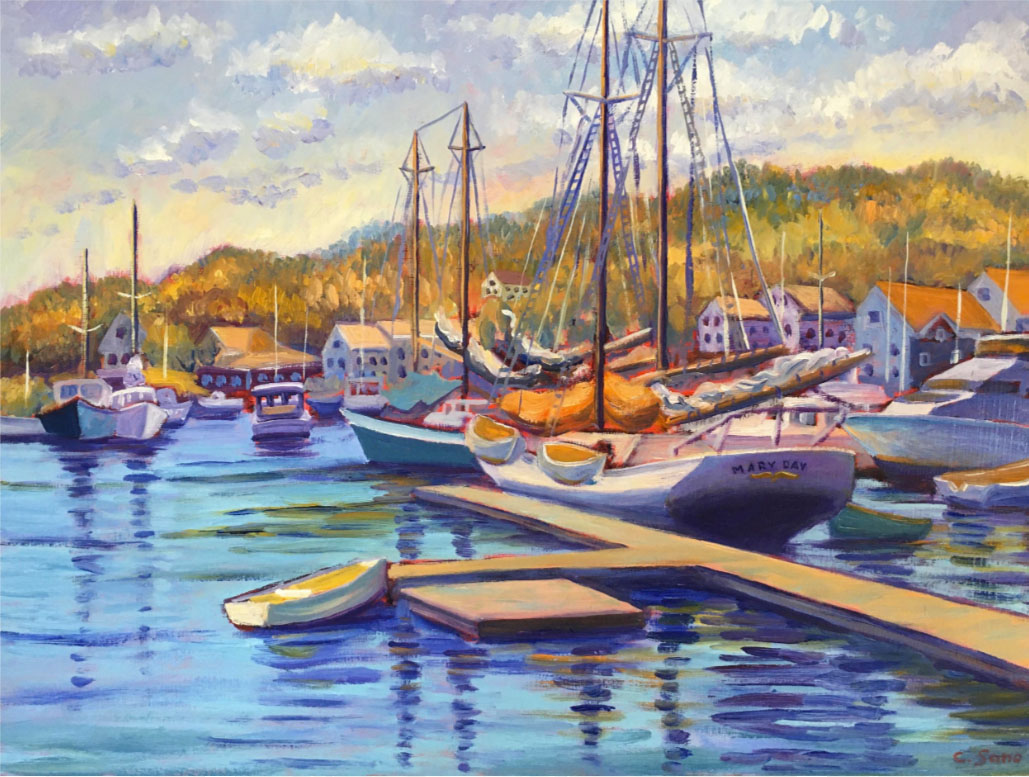

One of the students in this workshop is the wonderful painter Cassie Sano, who hails from Augusta, ME. That’s not nearly as sophisticated as you might think; really, she lives in the woods. She’s camping here in western Massachusetts and on the first day, she was dragging.

“I was up all night worrying about bears,” she told me.

“But you live in bear country!” I remonstrated.

“But at home I’m sleeping in my house!”

I told her all the comforting bear facts I could think of. When I got back to my daughter’s house in nearby Rensselaer County, NY, my son-in-law was cleaning up trash from a bear visit. We know they’re there; earlier this year we saw a sow and three cubs on the trail cam just behind the house.

My daughter inadvertently acquired a rooster this year. Besides chasing pullets around the yard, he starts crowing just before first light. That’s another sound with a powerful nostalgic kick, as is the outraged ‘no thanks!’ from a disinterested hen.

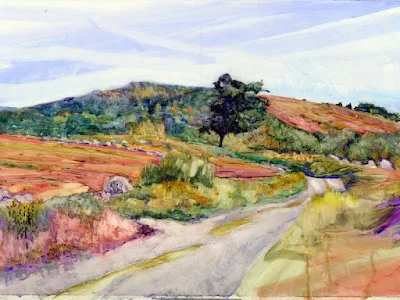

If you’ve been to Boston and New York, you know something about the northeast. Yes, it’s urban and industrialized. However, get out of the major cities and our region is rural. In many places, it’s wilderness. If you really want to know New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, you have to get out of town.

Wow

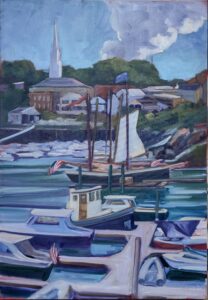

If you got an email from me yesterday, you know I’m doing an immersive workshop in Rockport in October. I wasn’t prepared for it to be so popular; as of this moment, more than half the seats are gone. I’m looking forward to sharing my beautiful town with you.

Artists, housing and one of my students.

Creative types sometimes struggle with affordable housing just like many others. A student of mine in Austin (Mark Gale) along with a colleague of his in St. Louis, are involved in finding and supporting solutions.

They are developing a panel discussion for the 2024 South by Southwest Conference (SXSW) that showcases three success. (SXSW gets national attention.) To bring this discussion to the public, though, they need votes via a simple thumbs up on the SXSW panel picker.

Or follow a direct link to vote.

The Austin program where Mark volunteers and one of those highlighted on the panel is Art from the Streets:

Voting closes 8/20, so please do it now.

My 2024 workshops:

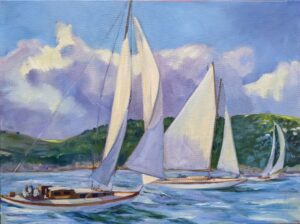

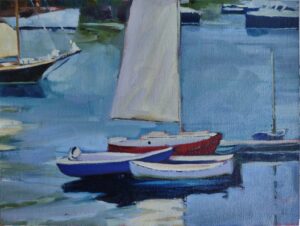

- Painting in Paradise: Rockport, ME, July 8-12, 2024.

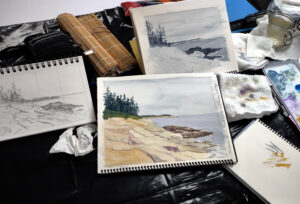

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic, August 4-9, 2024.

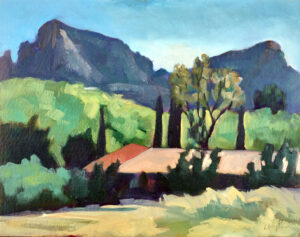

- Find your authentic voice in plein air: Berkshires, August 12-16, 2024.

- Art and Adventure at Sea: Paint Aboard Schooner American Eagle, September 15-19, 2024.

- Immersive In-Person Workshop: Rockport, ME, October 7-11, 2024.