Opening Saturday, May 31, 4-7 PM

Carol L. Douglas Studio/Richards Hill Gallery,

394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME, 04856

May 30-June 26, 2025

Tuesday-Sunday, Noon-5 PM

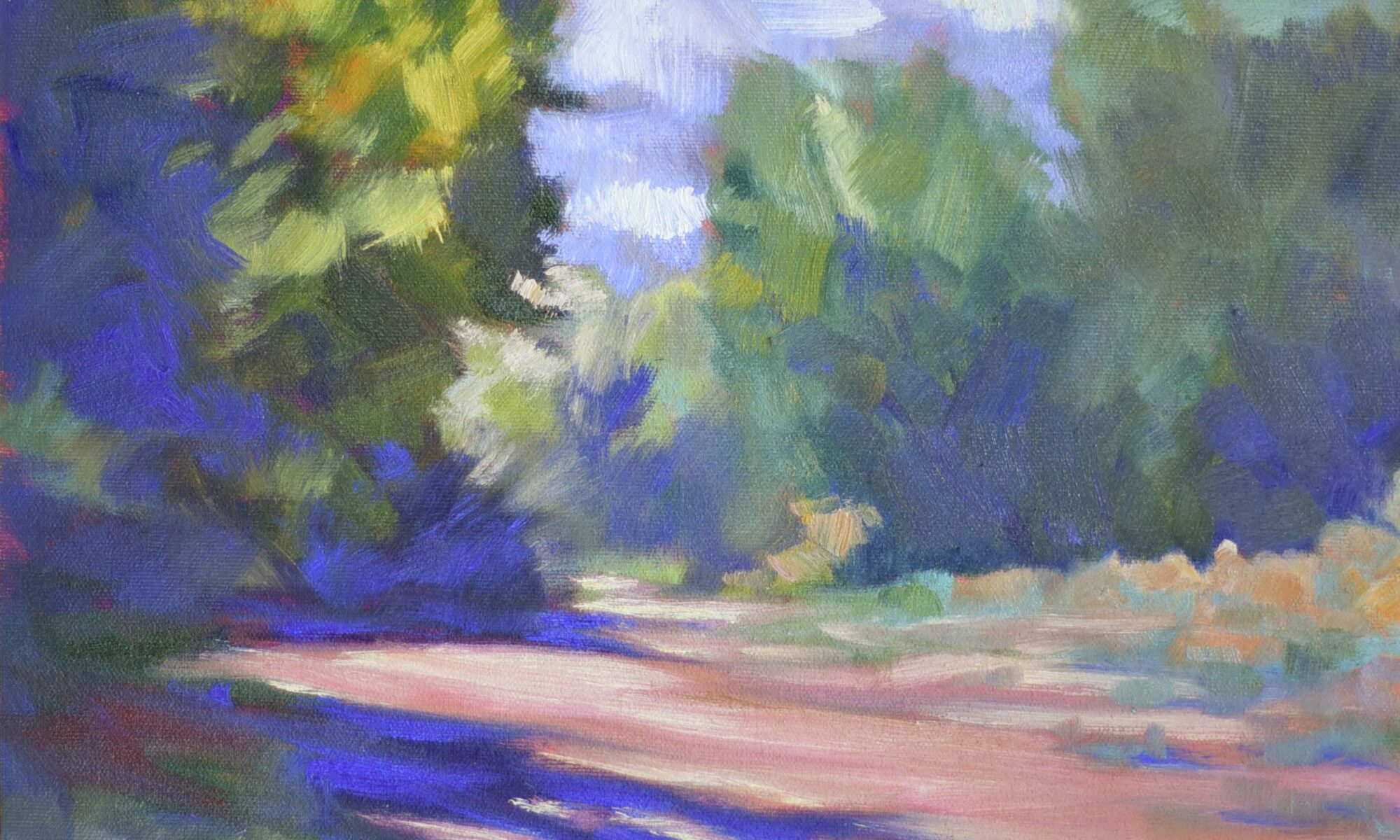

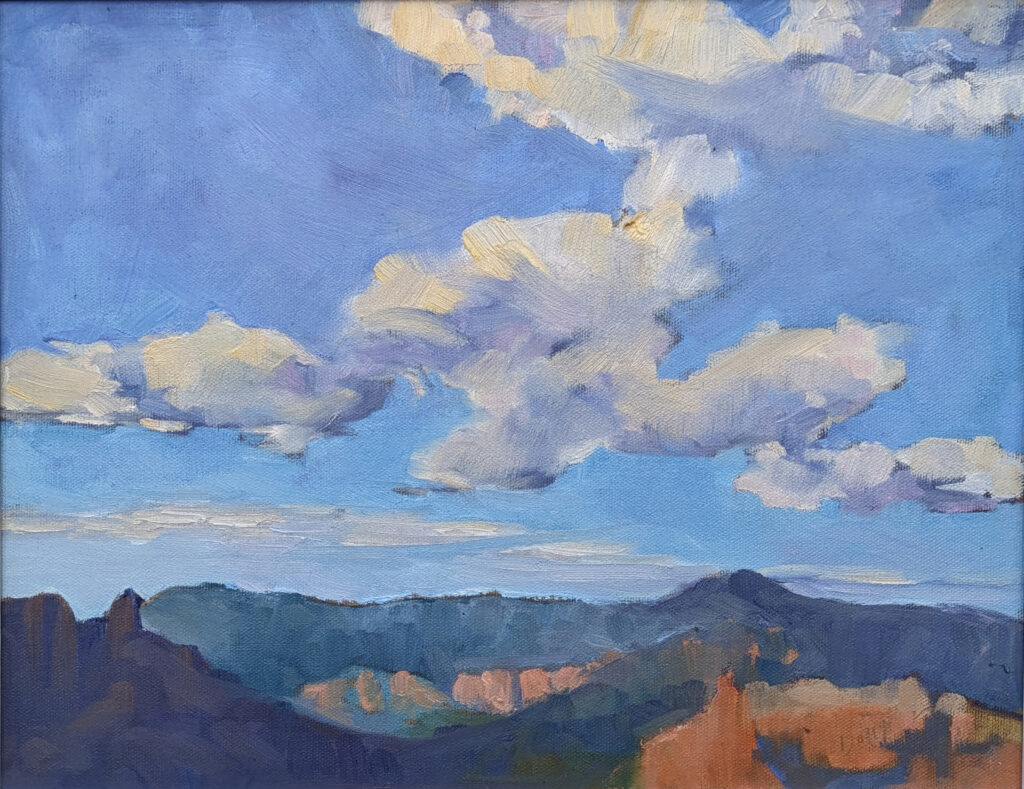

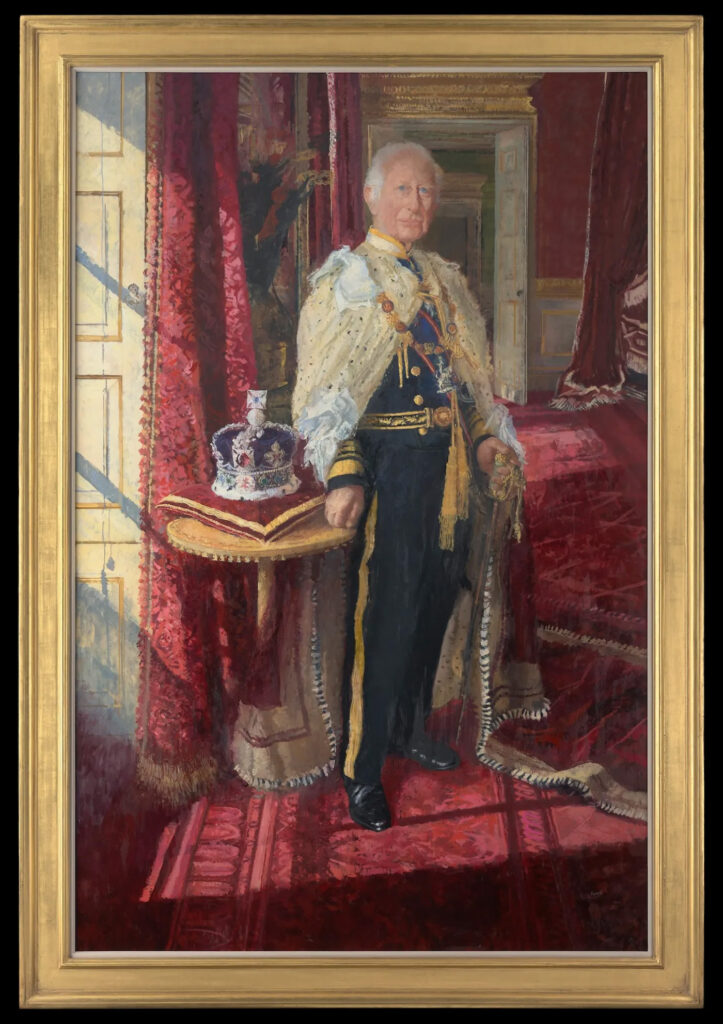

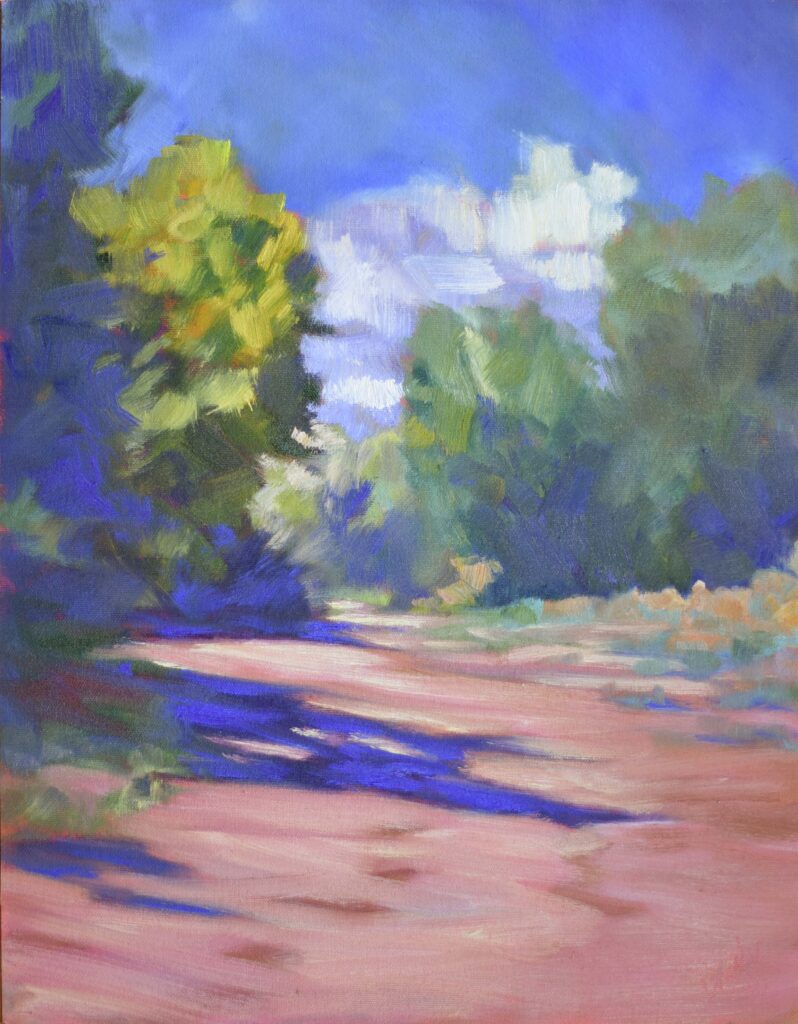

Certain places evoke collective nostalgia because they serve as shared universal touchstones. These are places where personal and collective memories intersect. Maine is one of them, which is why I’m calling my first show this season Letters from Home.

Letters from Home opens on Saturday, May 31 from 4-7 PM, at 394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME. If you don’t stop by for a glass of wine and hors d’oeuvres, I’ll be terribly disappointed. For one thing, I hate leftovers.

Collective nostalgia and the meaning of place

Maine is in New England, but it’s too north-woods to be in the top drawer of the social tea chest. (That’s true of much of northern New England, although the Yankee village-square and sugar maple aesthetic is universal.)

Still, Maine is a cultural touchstone of many virtues which we associate with New England. These include community, rugged individualism, self-sufficiency, respect for nature and hard work. I know we now like to adopt a cynical attitude about those things, but I submit that’s a pose. Even when we can’t succeed at them, we still, deep down, admire those traits. Our feelings about them are embedded in our collective nostalgia for Maine.

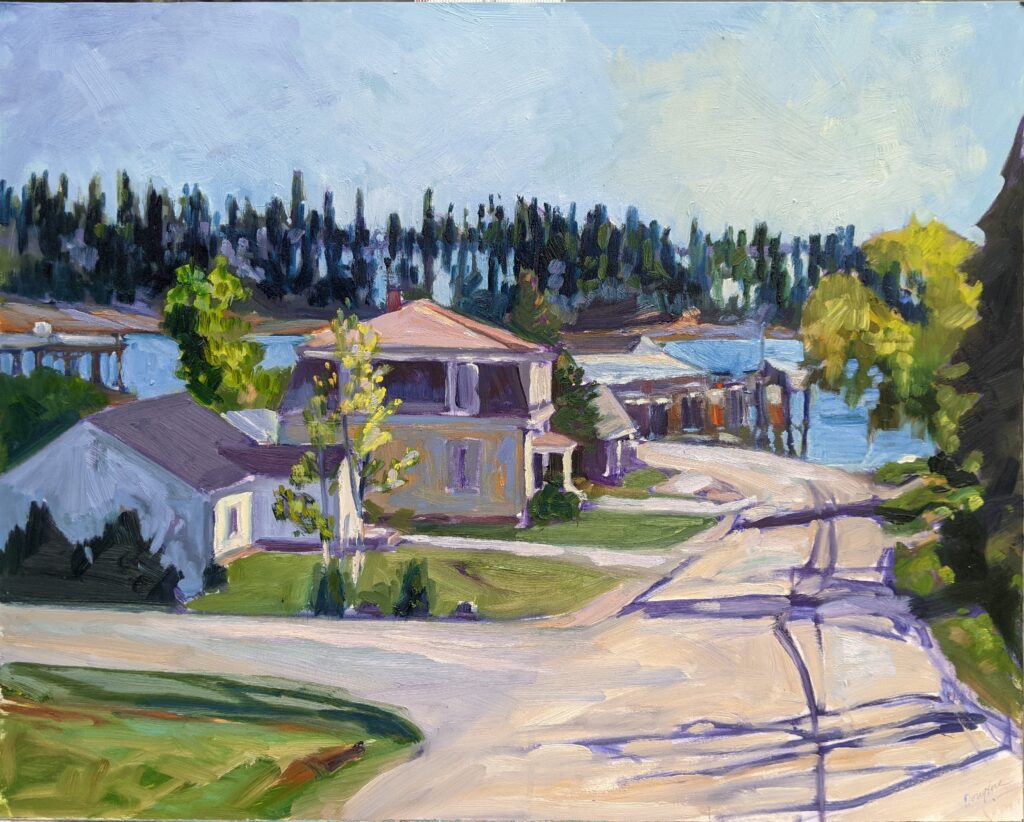

To most of America, Maine exists out of time. We’re all nostalgic for an America that once was, and the remnant of that exists here in Maine more than many other places. While most of my readers have never even visited my little town (but you should), we all have memories of a time when America had smaller communities, mom-and-pop motels, restaurants that weren’t chains and quieter roads. These memories may not even be from our own generation, but universal images that go back generations.

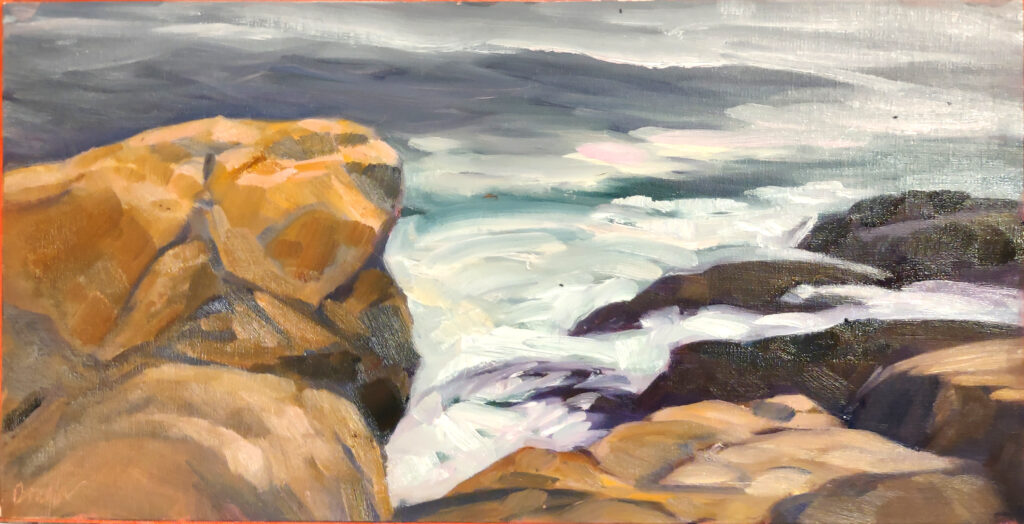

Places also carry an imprint of history. None of us are old enough to have hauled up cod onto the icy decks of schooners that plied the Grand Banks. However, we understand their importance, and are happy to see them, restored and resting in our harbors.

Not all these paintings are from Maine, because I don’t always paint here. But they’re all of things I think of as universal archetypes from the past. That’s our collective home.

Artists like me are, of course, terrible offenders at promoting collective nostalgia. We don’t do that cynically, or manipulatively. Like everyone else, we feel the pain of loss and change, so we paint what’s disappearing.

Please join me on May 31, from 4-7 PM for the opening of Letters from Home, at my gallery at 394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.